Stable#

Bacon, Plato, Aristotle Networks#

Francis Bacon, Plato, and Aristotle stand as monumental figures in philosophy, each representing a distinct mode of thinking that, if aligned with contemporary neuroscience, may correspond to major functional networks in the brain. The task-positive network (TPN), the default mode network (DMN), and what some call the “silent network” (a speculative name for minimally active but critical foundational systems) provide a framework through which we might explore their intellectual temperaments and contributions. Though this analogy is not a perfect fit, it offers a serious basis for studying the relationships between structured reasoning, introspective thought, and the deeper background of cognition.

Francis Bacon, the architect of the empirical method, is most naturally associated with the task-positive network. The TPN is engaged in focused, goal-directed activities, problem-solving, and active engagement with external reality. Bacon’s insistence on observation, experimentation, and inductive reasoning mirrors the brain’s mechanism for parsing the world in real-time, constructing causal relationships, and adapting through iterative refinement. The Novum Organum is not just a manifesto of empiricism but a blueprint for cognition that demands engagement with external stimuli, minimizing the biases of introspection in favor of structured, methodical inquiry. When the TPN is active, the DMN, which governs introspection and abstract reflection, is suppressed—a fitting metaphor for Bacon’s distrust of speculation and his pursuit of knowledge rooted in what can be measured and tested.

Plato, in contrast, embodies the default mode network, the seat of introspection, imagination, and the synthesis of abstract concepts. The DMN activates when the brain is at rest from external tasks, delving into memory, self-referential thought, and the exploration of hypothetical realities. Plato’s Republic and Timaeus function as paradigmatic DMN exercises, spinning intricate worlds of forms, ideal justice, and cosmology, largely independent of empirical validation. His skepticism toward the senses and his belief in a reality accessible only through reason and dialectic align with the DMN’s role in constructing abstract, high-level representations of the world. The philosopher who retreats from the cave of shadows to grasp the forms engages in a neurocognitive process that prioritizes deep contemplation over external engagement—a process that would be impaired if the task-positive network were dominant.

Aristotle occupies an intermediate space, resisting total alignment with either of the first two networks. He does not reject empirical observation as Plato does, but he also does not embrace the rigid empiricism of Bacon. This makes him a candidate for what might be called the “silent network,” a term speculative yet useful in considering fundamental neuroanatomical processes that serve as a substrate for both active cognition and introspection. Aristotle’s De Anima suggests a model of the soul as an integrative principle, unifying sensory perception, rational thought, and action—an idea that resonates with the silent network’s function as the bedrock upon which higher cognition operates. The Aristotelian approach, favoring a synthesis of reason and observation, is deeply compatible with the idea that cognition is neither purely abstract nor purely empirical but emerges from the integration of both.

If we were to assign a degree of fit between these philosophers and the networks, Bacon and the TPN would have the strongest correlation, with perhaps an 80-90% alignment, given his advocacy for structured engagement with the external world. Plato and the DMN would also align closely, around 85-95%, as his intellectual legacy is one of introspection, abstraction, and the pursuit of non-empirical truths. Aristotle’s relationship with the silent network is less direct, as the concept itself is still developing, but if we consider his model of cognition as fundamentally hierarchical and integrative, he may align with it at around 70-80%.

Ultimately, these figures illustrate not just different philosophies but different cognitive styles—distinct modes of engagement with reality that neuroscience is only beginning to map. To study neuroanatomy and neurophilosophy seriously, one must consider that thinking itself is not a monolithic act but a dynamic interplay between structured engagement, free contemplation, and the foundational processes that allow both to emerge.

Fig. 38 There’s a demand for improvement, a supply of product, and agents keeping costs down through it all. However, when product-supply is manipulated to fix a price, its no different from a mob-boss fixing a fight by asking the fighter to tank. This was a fork in the road for human civilization. Our dear planet earth now becomes just but an optional resource on which we jostle for resources. By expanding to Mars, the jostle reduces for perhaps a couple of centuries of millenia. There need to be things that inspire you. Things that make you glad to wake up in the morning and say “I’m looking forward to the future.” And until then, we have gym and coffee – or perhaps gin & juice. We are going to have a golden age. One of the American values that I love is optimism. We are going to make the future good.#

Psychological Terror and Fate#

The Knife’s Edge: Musk’s Adversarial Game and the Neural Fork of Fate

A low bar, yet a sharp guillotine—this is the paradox of Elon Musk’s ultimatum to the federal workforce. A simple email with five bullet points should take less than five minutes, Musk says, but the consequences of not responding are existential. The ultimatum is a game of incomplete information, a high-stakes iteration of psychological warfare where silence is construed as surrender, non-response as self-execution. This is not merely a mass firing; it is a game played at the knife’s edge, a compression of probability, agency, and fear into a singular moment of reckoning.

Within this moment, we see a dynamic that mirrors the fundamental architecture of intelligence, one embedded in the very structure of the human brain. At its most distilled, Musk’s decree forces federal employees through the neural fork—a transition from the single yellow node (compression, incomplete information, the flicker of a poker face) to the dual-path structure of ascending and descending agency. In the neural network of cognition, N1-N3 represent the ascending tracts—the drive, the initiative, the experimental group willing to leap into the unknown, who respond to the email with something—anything—that signals survival. N4-N5, the descending tracts, serve as the counterweight—the inhibitors, the cautious ones, the control group who hold back, either in defiance or in paralysis, resisting the demand, refusing to play. Their silence is read as resignation. In Musk’s framework, the system selects against them.

This is the second iteration of a bullying game, refined from its earlier form. In the first round, employees were explicitly asked to affirmatively resign—an act that required conscious submission, an active hand in one’s own removal. Many read the bluff and did not comply. Now, the adversarial equilibrium has been adjusted. The default is silence as acquiescence. The probability distribution is shifting, the evolutionary selection pressure heightened. This is no longer poker, where skilled players suppress their autonomic responses, keep a steady hand, and bait their opponents into making a move. This has moved into the realm of the knife’s edge—Formula One racing, where a single miscalculation means catastrophe, or sprinting, where victory is measured in fractions of a second. The game is forcing players into strategic adaptation, just as Noah Lyles edged out his Jamaican competitor not by sheer speed alone, but by the technique of the lean, a calculated, premeditated act of advantage at the last possible moment.

But the psychological cost is immense. “I don’t know how we can keep up with this psychological terror,” an employee laments. Here, we see the sympathetic nervous system fully engaged—fight, flight, or fright. Musk’s decree is designed to induce panic, to trigger the amygdala into a state of hypervigilance. In the neural hierarchy, this is the moment of crisis: does the individual engage G3, the transactional jostling between sympathetic and parasympathetic states, and regain composure? Or do they remain ensnared in the adversarial stress cycle, perpetually on edge, until exhaustion, error, or inaction consumes them?

This is a game of adversarial pruning, a live stress test of adaptability under uncertainty, a forced compression of agency and reason. The judiciary was inadvertently caught in the crossfire, receiving the email despite their nominal separation from executive power—a misfire in the execution of control, a blunder that, in a game of chess or warfare, might signal a crack in the machinery. Yet the logic of warfare is embedded within the strategy itself. Knowledge, accumulated through trial and error, is the currency of survival. The ability to discern the parameters of engagement, to anticipate the next move, to inherit and wield the structures of power, determines who prevails and who falls.

Musk, in his characteristic way, frames it as efficiency. “An email with some bullet points that make any sense at all is acceptable!” The demand is dressed in the language of triviality, but the stakes are absolute. At the final layer of cognition—certainty—the game is revealed for what it is: a forced dichotomy between complete compliance and total exclusion. The demand is for a leap, an affirmation, a commitment made with both feet off the ground, eyes shut. It is a declaration of faith in the system or an acknowledgment of its unworthiness. The vow, once made, resembles the words spoken at an altar—*”till death do us part”—*a promise of permanence in a framework that offers no guarantees.

The federal workforce stands at the crossroads of this game, its employees forced to decide whether to yield to the terms of engagement or to resist and face obliteration. Yet within this moment lies a deeper truth, a revelation of the system’s own limits. The fork Musk has created, the adversarial selection he has engineered, operates under the assumption that compliance equates to competency, that resilience in the face of psychological warfare is the marker of value. But history—like a well-trained neural network—has seen this pattern before. Compression, iteration, emergence: these cycles do not merely select for survival; they reconfigure the very nature of the game itself.

The question is not whether employees will respond to the email. It is whether they will allow the rules of the game to remain unchanged.

Wokeness and Thallamocortical Gating#

Thalamocortical gating is one of the brain’s most fascinating and underrated mechanisms—a complex process that filters and prioritizes sensory information before it ever reaches our conscious awareness. In this neural symphony, the thalamus serves as a discerning gatekeeper, allowing only the most salient signals to pass through to the cortex, ensuring that our minds are not overwhelmed by the relentless barrage of stimuli. This intricate filtering not only underpins our cognitive clarity but also reveals a deeper metaphor about how we navigate the world: by constantly sifting through noise to focus on what truly matters.

In a surprisingly analogous fashion, the modern social phenomenon of being “woke” attempts to filter and recalibrate our collective consciousness. Being woke is not merely a trendy label; it is a vigorous, sometimes controversial, call to awareness that challenges outdated norms, systemic injustices, and cultural complacency. Much like the thalamus that instinctively suppresses irrelevant sensory input, woke culture seeks to block out the pervasive, often toxic narratives that have long distorted our understanding of social dynamics. However, unlike the finely tuned, evolutionarily honed mechanism of thalamocortical gating, the process of becoming woke is a human construct—one that is messy, highly charged, and all too often riddled with contradictions.

I contend that the underlying drive to be woke is both noble and necessary. In an era where historical inequities continue to manifest in everyday injustices, there is a vital need for a societal mechanism that calls out and filters out regressive ideas. Yet, the modern incarnation of wokeness frequently veers into self-righteous territory. Its adherents can become so fixated on purging every remnant of the old order that the movement risks devolving into an echo chamber of ideological purity. In its most extreme form, being woke can mirror the very rigidity it seeks to dismantle, becoming intolerant of nuance and open debate. This overzealousness does not reflect the elegant, balanced filtering of thalamocortical gating; rather, it resembles a malfunctioning system that indiscriminately shuts down dissenting perspectives, sometimes to the detriment of genuine progress.

There is an inherent irony in comparing a deeply biological process to a social and political movement. The thalamus operates without bias, its gating functions refined over millennia to optimize our interaction with an ever-changing environment. In contrast, the social mechanism of wokeness is uncomfortably tied to human emotion and politics, making it susceptible to the vagaries of subjective judgment. While the biological process is a marvel of evolutionary efficiency, the social process, though well-intentioned, often suffers from the pitfalls of extremism and a lack of balanced introspection. It is this imbalance that troubles me: the insistence on moral purity in public discourse can sometimes obscure the very truths it seeks to illuminate.

At its best, being woke is an essential corrective—a radical rethinking of how we view power, history, and identity. It challenges us to recognize and dismantle the subtle filters that society has long imposed on marginalized voices. However, when the zeal for being woke eclipses rational debate and empathy, it loses its transformative potential and begins to mirror the inefficiencies of a poorly tuned neural filter. Just as the thalamus must strike a precise balance between inhibition and facilitation, society too must learn to temper its revolutionary impulses with careful reflection and an openness to diverse perspectives.

In essence, the comparison between thalamocortical gating and being woke serves as a potent reminder of the delicate balance required in both our minds and our societies. The brain’s ability to filter and prioritize is a testament to natural evolution’s genius—a system that manages to maintain equilibrium in the face of chaos. On the other hand, while the pursuit of social justice through wokeness is undeniably critical, it demands a similar level of finesse. Without it, the movement risks becoming as indiscriminate as a malfunctioning gate, shutting out not just the harmful signals but also the constructive dialogue that is necessary for real, lasting change.

Ultimately, I believe that we must strive to cultivate a form of social consciousness that mirrors the brain’s elegance—one that filters out the noise of prejudice and ignorance while remaining open to the complexity of human experience. Embracing the spirit of being woke, when done with nuance and self-awareness, can indeed lead to a more enlightened society. Yet, it must be constantly recalibrated, lest it devolve into a rigid ideology that, much like an overzealous neural filter, hinders rather than enhances our collective progress.

Show code cell source

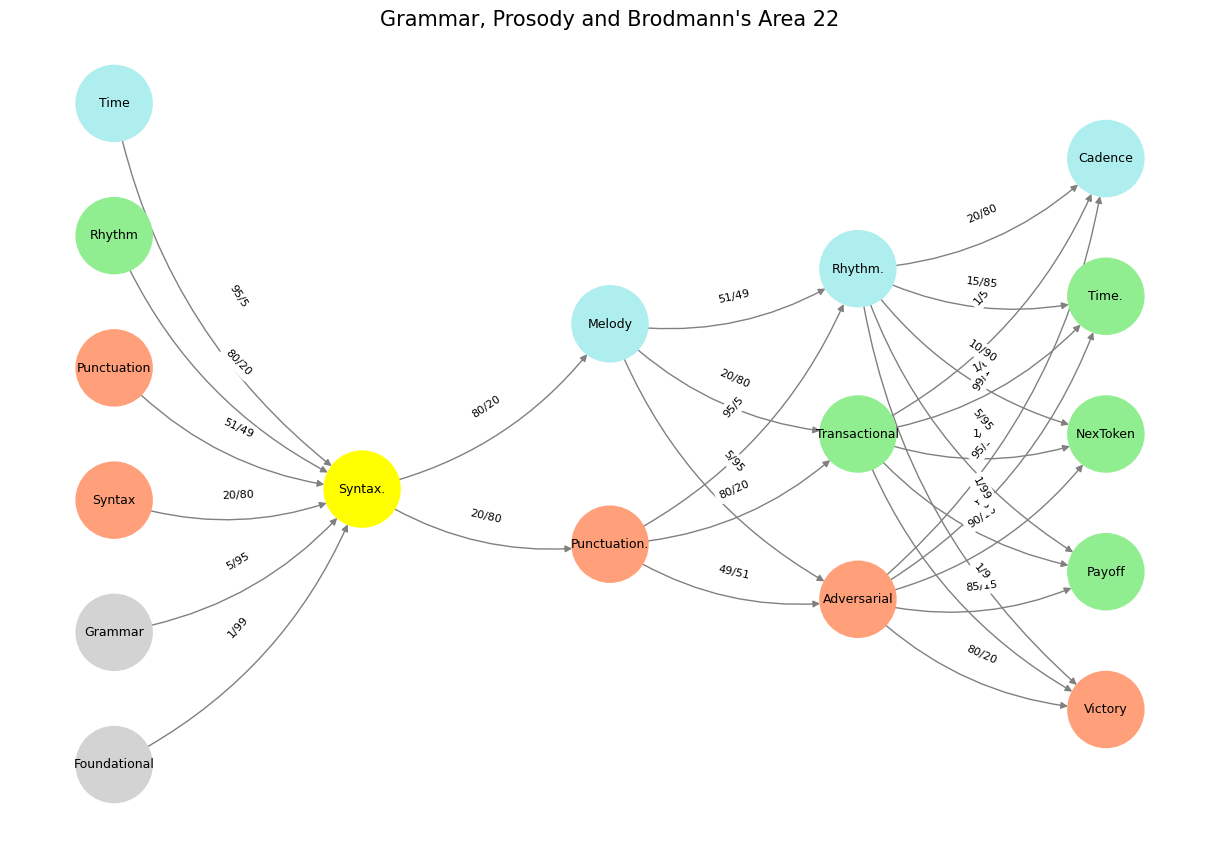

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Suis': ['Foundational', 'Grammar', 'Syntax', 'Punctuation', "Rhythm", 'Time'], # Static

'Voir': ['Syntax.'],

'Choisis': ['Punctuation.', 'Melody'],

'Deviens': ['Adversarial', 'Transactional', 'Rhythm.'],

"M'èléve": ['Victory', 'Payoff', 'NexToken', 'Time.', 'Cadence']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Syntax.'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time', 'Melody', 'Rhythm.', 'Cadence'],

'lightgreen': ["Rhythm", 'Transactional', 'Payoff', 'Time.', 'NexToken'],

'lightsalmon': ['Syntax', 'Punctuation', 'Punctuation.', 'Adversarial', 'Victory'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights (hardcoded for editing)

def define_edges():

return {

('Foundational', 'Syntax.'): '1/99',

('Grammar', 'Syntax.'): '5/95',

('Syntax', 'Syntax.'): '20/80',

('Punctuation', 'Syntax.'): '51/49',

("Rhythm", 'Syntax.'): '80/20',

('Time', 'Syntax.'): '95/5',

('Syntax.', 'Punctuation.'): '20/80',

('Syntax.', 'Melody'): '80/20',

('Punctuation.', 'Adversarial'): '49/51',

('Punctuation.', 'Transactional'): '80/20',

('Punctuation.', 'Rhythm.'): '95/5',

('Melody', 'Adversarial'): '5/95',

('Melody', 'Transactional'): '20/80',

('Melody', 'Rhythm.'): '51/49',

('Adversarial', 'Victory'): '80/20',

('Adversarial', 'Payoff'): '85/15',

('Adversarial', 'NexToken'): '90/10',

('Adversarial', 'Time.'): '95/5',

('Adversarial', 'Cadence'): '99/1',

('Transactional', 'Victory'): '1/9',

('Transactional', 'Payoff'): '1/8',

('Transactional', 'NexToken'): '1/7',

('Transactional', 'Time.'): '1/6',

('Transactional', 'Cadence'): '1/5',

('Rhythm.', 'Victory'): '1/99',

('Rhythm.', 'Payoff'): '5/95',

('Rhythm.', 'NexToken'): '10/90',

('Rhythm.', 'Time.'): '15/85',

('Rhythm.', 'Cadence'): '20/80'

}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with weights

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in G.nodes and target in G.nodes:

G.add_edge(source, target, weight=weight)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("Grammar, Prosody and Brodmann's Area 22", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 39 Icarus represents a rapid, elegant escape from the labyrinth by transcending into the third dimension—a brilliant shortcut past the father’s meticulous, earthbound craftsmanship. Daedalus, the master architect, constructs a tortuous, enclosed structure that forces problem-solving along a constrained plane. Icarus, impatient, bypasses the entire system, opting for flight: the most immediate and efficient exit. But that’s precisely where the tragedy lies—his solution works too well, so well that he doesn’t respect its limits. The sun, often emphasized as the moralistic warning, is really just a reminder that even the most beautiful, radical solutions have constraints. Icarus doesn’t just escape; he ascends. But in doing so, he loses the ability to iterate, to adjust dynamically. His shortcut is both his liberation and his doom. The real irony? Daedalus, bound to linear problem-solving, actually survives. He flies, but conservatively. Icarus, in contrast, embodies the hubris of absolute success—skipping all iterative safeguards, assuming pure ascent is sustainable. It’s a compressed metaphor for overclocking intelligence, innovation, or even ambition without recognizing feedback loops. If you outpace the system too fast, you risk breaking the very structure that makes survival possible. It’s less about the sun and more about respecting the transition phase between escape and mastery.#