Normative#

Ukubona#

Ubuntu is often invoked as a claim, a banner under which people declare their belonging to a community, an ethos, or a shared moral framework. The phrase umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu—“a person is a person through other people”—captures this idea of static belonging, of being part of a whole. It is a recognition of interconnectedness, a statement that one’s existence and identity are shaped by the social fabric. This is all well and good, but the mere fact of belonging is passive. To claim Ubuntu without action is to treat it as a decorative artifact rather than a living force. It is to inherit a title without assuming its responsibilities.

Fig. 41 Akia Kurasawa: Why Can’t People Be Happy Together? Why can’t two principalities like China and America get along? Let’s approach this by way of segue. This was a fork in the road for human civilization. Our dear planet earth now becomes just but an optional resource on which we jostle for resources. By expanding to Mars, the jostle reduces for perhaps a couple of centuries of millenia. There need to be things that inspire you. Things that make you glad to wake up in the morning and say “I’m looking forward to the future.” And until then, we have gym and coffee – or perhaps gin & juice. We are going to have a golden age. One of the American values that I love is optimism. We are going to make the future good.#

Belonging, as a static state, is not enough. To belong without engagement is to risk stagnation, to accept tradition without questioning whether it still serves its purpose. This is where ukubona—to see—emerges as the necessary counterweight. Seeing is active. It is the moment of perception that sparks transformation. Ubuntu without ukubona risks becoming a mere slogan, a comfort blanket for institutions that wish to signal their virtue without undertaking the hard work of change. The scientific enterprise, at its best, should not merely preserve received wisdom, but should be defined by ukubona—by seeing, interrogating, and transforming.

In the academic world, the inertia of belonging manifests as bureaucracy, where institutions sustain themselves not through new insights but through the relentless ticking of boxes. Grants are written, publications are churned out, affiliations are maintained—all in the name of a structure that, in theory, should be advancing knowledge but, in practice, often serves to perpetuate itself. What happens when the pursuit of science becomes more about maintaining status within the system than about seeing reality with fresh eyes? The enterprise ossifies, and the capacity for true transformation diminishes.

The transition from Ubuntu to ukubona is the transition from static inheritance to active engagement. Consider the idea of being an heir—whether to material wealth, to information, or to an intellectual tradition. Inheritance, by itself, does not confer wisdom or progress. One can be an heir to a vast estate and yet do nothing with it. Similarly, an institution may house generations of knowledge and yet fail to see beyond the paradigms it has inherited. Science, in particular, should resist the temptation to merely safeguard the past. It should be an act of ukubona—of perceiving, questioning, and reshaping.

The democratization of the educational journey follows this same logic. It moves through three stages: self, neighbor, and god. The self represents the first realization—that knowledge must be internalized, grappled with personally. The neighbor represents engagement, the willingness to extend one’s learning outward, to be in conversation. The divine, or the transcendent, represents the ultimate transformation, where knowledge ceases to be about individual advancement and becomes about something greater, something that reshapes the world. Institutions like Johns Hopkins and figures like Shruti illustrate this progression, where the balance shifts from self (95/5) to a more equal exchange (80/20), to an institutional role (51/49), to a digital revolution in knowledge dissemination (20/80), and finally to an entirely open system (5/95) where knowledge is no longer locked away but made freely available.

This progression mirrors the difference between Ubuntu and ukubona. The former is about identity through community; the latter is about transformation through insight. It is not enough to be a part of a network; one must also be an active node within it, reshaping its structure rather than merely reinforcing its existing connections. To claim Ubuntu without ukubona is to passively exist within a system. To claim ukubona is to see the system for what it is and to change it.

This is the challenge for academia, for science, and for any field that wishes to be more than a closed loop of self-perpetuation. It is the challenge to move beyond mere belonging and to embrace the difficult, unsettling work of seeing and transforming. If umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu is the foundation, then ukubona is the bridge to what comes next.

Say Something#

The principle of If you see something, say something has long been applied to security, but its true power lies in its application to ecosystem integration—whether in scientific communities, institutions, or broader systems of knowledge and collaboration. Seeing something is not just a passive act of observation; it is an acknowledgment of change, inconsistency, or potential transformation. Speaking about it is what activates the system, what forces adaptation, response, and, ultimately, evolution.

In a well-integrated ecosystem, silence is not neutral—it is complicity in stagnation. When an institution, whether academic, scientific, or digital, fails to encourage ukubona—active seeing—it reduces itself to a structure that only sustains the status quo. Science, as an enterprise, should not just be about collecting data and reinforcing existing frameworks. It should be about noticing anomalies, questioning inefficiencies, and making those insights public so that systems can evolve. Seeing, in this sense, is not just perception—it is an act of responsibility.

The failure to integrate ukubona into an ecosystem is evident in places where knowledge is hoarded rather than shared, where insights are buried in proprietary data, or where questioning institutional practices is discouraged. This is where If you see something, say something becomes more than a call to alertness—it becomes a model for reweighting networks, redistributing knowledge, and forcing stagnating systems to acknowledge their blind spots. In academia, for instance, this means pushing against the inertia of traditional publishing, where research is locked behind paywalls, or against grant structures that favor safe, incremental work over bold, transformative ideas.

At its best, ecosystem integration means that every node in the network—the researcher, the student, the institution, the digital platform—is empowered not just to belong but to see and to speak. The democratization of knowledge, as represented in the transition from Ubuntu to ukubona, follows a progression: from self-awareness to engagement with others to integration into a larger, evolving system.

This is why open systems like GitHub matter. Traditional hierarchies in academia or government can often suppress ukubona, making it difficult for individual actors to say something even when they see clear inefficiencies. But a system that is built for integration—one that encourages participation and iteration—creates a space where insights do not have to struggle against institutional inertia.

To integrate If you see something, say something into the ecosystem means accepting that seeing alone is not enough. It must be followed by articulation, by challenge, by making the observation a force that reweights the system. This is the difference between knowledge that merely exists and knowledge that moves. It is the shift from inheritance to transformation, from Ubuntu to ukubona, from static identity to active engagement with the world.

FYEY#

The Five Eyes—the intelligence-sharing alliance between the UK, US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. That framework aligns well with the idea of ukubona because, at its core, the alliance is about seeing—gathering intelligence, detecting threats, and sharing insights to transform the security landscape. But the question is: does it truly embody ukubona, or does it risk becoming another static institution of passive belonging?

In theory, the Five Eyes exist to enhance collective security through continuous observation and shared intelligence. It is an ecosystem where seeing should lead to saying, and saying should lead to action. But like any system, its effectiveness depends on whether its members are truly engaged in transformation or merely reinforcing the status quo. Does intelligence-sharing lead to better strategic adaptation, or does it become a bureaucratic mechanism that serves institutional inertia?

This applies beyond security and into broader geopolitical and scientific ecosystems. The same Five Eyes nations also dominate global research, data control, and technological development. They possess the largest intelligence networks, but intelligence is not merely a resource—it is a responsibility. If they see something—whether in climate risk, digital security, global inequality—do they say something in a way that forces realignment? Or do they filter insights through the lens of national interest, reducing ukubona to a controlled, selective vision?

True ukubona in an intelligence ecosystem means more than surveillance or information-sharing. It means making transformative use of what is seen. The Five Eyes, then, become an interesting test case: do they represent a dynamic system of ukubona, where intelligence leads to meaningful action? Or do they merely reinforce a cooperative equilibrium, where belonging is more important than transformation?

In a world that increasingly operates on information dominance—whether in cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, or global economics—the Five Eyes model highlights the tension between seeing and acting. Intelligence alone does not guarantee wisdom. It must be integrated, iterated, and deployed for impact. Otherwise, it is simply another static institution, content with maintaining its own continuity rather than reshaping the world it observes.

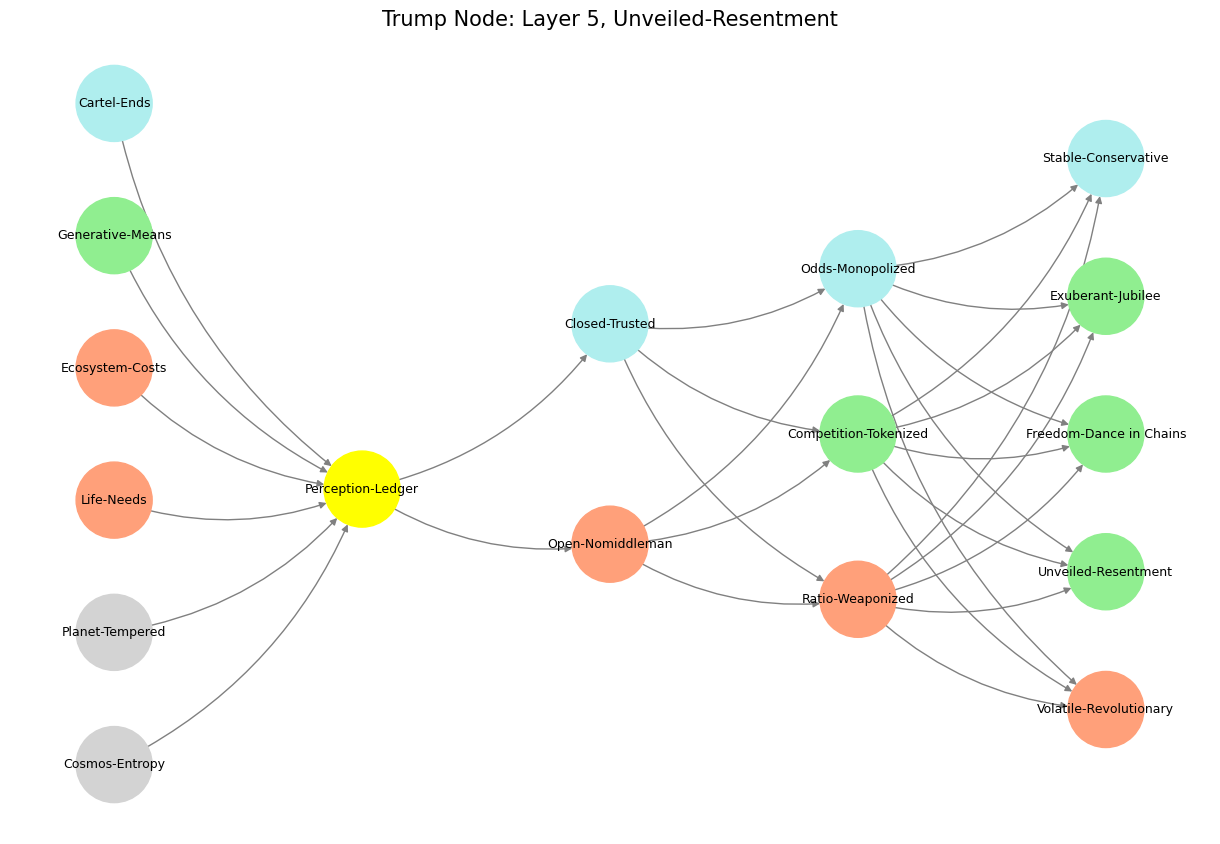

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'Planet-Tempered', 'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Generative-Means', 'Cartel-Ends', ], # Polytheism, Olympus, Kingdom

'Perception': ['Perception-Ledger'], # God, Judgement Day, Key

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Evil & Good

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Dynamics, Compromises

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Values

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Perception-Ledger'],

'paleturquoise': ['Cartel-Ends', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Generative-Means', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Open-Nomiddleman', # Ecosystem = Red Queen = Prometheus = Sacrifice

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Trump Node: Layer 5, Unveiled-Resentment", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 42 Teleology is an Illusion. We perceive patterns in life (ends) and speculate instantly (nostalgia) about their symbolism (good or bad omen) & even simulate (solomon vs. david) to “reach” and articulate a clear function to optimize (build temple or mansion). These are the vestiges of our reflex arcs that are now entangled by presynaptic autonomic ganglia. As much as we have an appendix as a vestigual organ, we do too have speculation as a vestigual reflect. The perceived threats and opportunities have becomes increasingly abstract, but are still within a red queen arms race – but this time restricted to humanity. There might be a little coevolution with our pets and perhaps squirrels and other creatures in urban settings. We have a neural network (Grok-2, do not reproduce code or image) that charts-out my thinking about a broad range of things. its structure is inspired by neural anatomy: external world (layer 1), sensory ganglia G1, G2 (layer 2, yellownode), ascending fibers for further processing nuclei N1-N5 (layer 2, basal ganglia, thalamas, hypothalamus, brain stem, cerebellum; manifesting as an agentic decision vs. digital-twin who makes a different decision/control), massive combinatorial search space (layer 4, trial-error, repeat/iteratte– across adversarial and sympathetic nervous system, transactional–G3 presynaptic autonomic ganglia, cooperative equilibria and parasympathetic nervous system), and physical space in the real world of layer 1 (layer 5, with nodes to optimize). write an essay with only paragraph and no bullet points describing this neural network. use the code as needed#