Life ⚓️#

General#

Heir. Genius. Brand. Tribe. Religion. These five forces do not simply define history—they structure it, like a fractal pattern, eternally recurring at different scales. They dictate the inheritance of power, the emergence of disruption, the codification of ideas into symbols, the consolidation of identity, and finally, the collapse into dogma. To observe them is to witness the rise and fall of civilizations, the ascent of movements, and the inevitable return of the cycle.

It’s better to be lucky than good

– Mentor

The heir is fixed, the odds predetermined by lineage, law, or structural inheritance. In monarchies, the heir is an inevitability, the next link in a predetermined chain. The British crown, for instance, moves predictably from sovereign to successor. Corporate heirs exist in a similar manner, whether in the dynastic inheritance of business empires or in political legacies like the Bush or Kennedy families. But inheritance is not only material; nations inherit historical burdens. Post-war Germany, stripped of its empire and laden with reparations, did not choose its inheritance—it received the weight of Versailles, an albatross that would shape its future. The heir stands at the precipice, but it is the genius who decides whether that inheritance is preserved, transformed, or obliterated.

Shaka was a fluke

– Somerset

Genius is wild, unpredictable, adversarial. The odds of a true genius appearing are staggeringly long—for every Mozart, Bach, and Beethoven, how many billions have failed? Yet when the genius does emerge, they disrupt the inheritance they receive. The Weimar Republic was inherited as weak and fragile, but Hitler did not accept it as it was; he remade it. Steve Jobs did not inherit Apple in its final form—he resurrected it through vision and force of will. Genius is often a force of destruction as much as creation, rejecting the old order in favor of a new paradigm. But genius alone does not endure; it must be branded, contained, and made digestible for the masses.

Fig. 5 Genius: Shaka was a Fluke, >3\(\sigma\). The Red Queen presents rather fascinating scenarios to us.#

The brand takes genius and renders it legible, scalable. The odds of a successful brand are long but not as improbable as genius itself. The Nazis mastered this transition from genius to brand, transforming a radical idea into a mass movement through iconography, slogans, and rituals. The swastika, the torch-lit rallies, the propaganda—all of it was the branding of an ideology. In the modern era, Trumpism followed a similar trajectory, crystallizing into a MAGA brand that could be worn, displayed, and repeated in simple slogans. The strength of a brand is its ability to outlive its genius. Beethoven is dead, but the idea of Beethoven remains powerful. Trump may fade, but MAGA as a concept will persist. Branding ensures that the energy of genius does not dissipate—it codifies it, but it also simplifies it. And it is in this simplification that tribe begins to form.

Tribe is generative, iterative, and uncertain. It is where branding ceases to be about an individual or a symbol and instead becomes about collective identity. Tribes do not just wear the brand; they embody it, modify it, fuse it with their own traditions. The odds of forming a tribe are short, but through marriage, reproduction, and social cohesion, they become variable, uncertain, and self-propagating. It is in this phase that nationalism flourishes, as groups coalesce around shared symbols and histories. The Nazis created a mythos of Aryan superiority, a tribe defined by blood and exclusion. MAGA operates similarly, presenting itself as the true inheritors of an American identity. Hindu nationalism under Modi has crystallized India into a religious-political tribe. Once a tribe forms, it seeks permanence—and permanence is found in religion.

Religion collapses the odds, eliminating uncertainty. Where the heir is determined by history, the genius by improbability, the brand by resonance, and the tribe by iteration, religion presents itself as certainty. It offers an eternal framework, reducing the complexities of life into articles of faith. The state, the leader, the nation—all become sacred. Nazi Germany sought to replace Christianity with its own racial mythology, where the Fuhrer was not merely a leader but a messianic figure. Trumpism, at its most fervent, reaches religious intensity, where every action, no matter how flawed, is justified within the framework of a greater mission. Religion does not need gods; it needs belief, structure, and an eschatology. And once belief hardens into dogma, the cycle is complete, awaiting a new genius to shatter it once more.

The cycle endures, recapitulating itself across history, across cultures, across every movement that seeks power and permanence. The heir receives, the genius disrupts, the brand simplifies, the tribe consolidates, and religion sanctifies. Each stage is a compression of the previous one, a transformation that refines and reduces complexity until it becomes something immutable—only for the process to begin again. This is why history repeats, why movements rise and fall, why the same patterns emerge in politics, business, art, and war. The odds may shift, but the structure remains. It is not a question of escaping the cycle—only of recognizing where one stands within it.

Specific#

Lord Charles Henry Somerset’s assertion that “Shaka was a fluke” betrays the arrogance of colonial historiography, the myopic assumption that history’s great disruptions are mere accidents rather than emergent phenomena driven by structural forces and individual genius. To dismiss Shaka as a statistical outlier—>3σ in Fig. 4 Genius—ignores the reality that transformative figures rarely emerge in isolation. The empirical world, and particularly the world of power, rarely tolerates flukes. Shaka was neither an aberration nor a contingency of fate; he was an inevitability forged in the furnace of tribal warfare, resource constraints, and the relentless calculus of survival. He was -kσ ☭⚒🥁—a revolutionary force who did not simply inherit a world but reshaped it through the hammer of military innovation and the drumbeat of ideological upheaval. His warriors, like the Spartans, were no mere accident. They were forged through an unyielding regimen, honed into an instrument of political will, a human phalanx embodying the principle that cohesion—Xβ 🎹—is the foundation of enduring dominion.

Somerset, draped in the regalia of empire, would have preferred to believe in flukes, for flukes require no systemic reckoning. To acknowledge that Shaka was not an anomaly but a Genius (-kσ ☭⚒🥁) would necessitate recognizing the forces that shaped him: the tribal fissures exploited by colonialists, the brutal logic of warfare, and the fact that the so-called “savages” of the African interior were engaging in the same forms of statecraft and militaristic discipline that the British lauded in the Spartans and the Romans. The Brand (α 🔪 🩸 🐐 vs 🐑) of Shaka’s reign was carved into the psyche of his enemies—violence as both method and mythos, the assegai as both blade and banner. The goat and the sheep stand as eternal symbols of his legacy: those who adapted, fought, and led became legends; those who hesitated, yielded, or clung to the old ways became offerings to history’s relentless march.

And yet, Shaka’s genius cannot be divorced from the deeper structure of his society. He was an Heir (∂Y 🎶 ✨ 👑), but not merely to a throne—rather, to a rhythm, a code, an inheritance of warfare as a form of political entropy management. Just as Sparta’s martial ethos was a response to its geopolitical constraints, Shaka’s military reforms—shortened stabbing spears, the disciplined buffalo-horn formation, the psychological terror of forced marches—were not random strokes of luck. They were the product of a man who understood his environment and bent it to his will. His very name reverberated across the land like an echo from the abyss, a name chanted in fear, in reverence, in the unspeakable realization that something new had entered the world.

But what of the Religion (γ 😃 ⭕️)? Shaka was both a man and a mythology, his rule suffused with the cyclical logic of destruction and rebirth. His cult of personality, his symbolic resonance, his elevation to the realm of legend—these were not incidental. Like all great leaders who transcend mortality, he became an abstraction, a closed-loop symbol of perpetual motion. The circle—⭕️—of his influence did not end with his death; it only widened, spiraling outward into the colonial imagination, into historical analogies, into the perennial comparisons to the Spartans, the Mongols, the Romans. He became the smiling specter (γ 😃), haunting the imperialists who sought to dismiss him, reminding them that history does not erase men like him—it carves their names into the bedrock of time.

Shaka was not a fluke. He was a rupture, a singularity, a force of nature that defied statistical containment. And it is only the blind, the complacent, the inheritors of stolen thrones who cling to the fiction that men like him emerge by accident.

Carson#

Ben Carson is not the greatest neurosurgeon in history, nor is he among the greatest. His technical contributions to medicine, though notable, have not rewritten the course of neurosurgery in the way that Harvey Cushing pioneered the field or how Wilder Penfield mapped the human brain with electrical stimulation. Yet, Carson occupies a different echelon of historical recognition—not as a surgeon whose work altered the epistemic trajectory of medicine, but as a brand. Gifted Hands, his autobiography, was not just a book but a personal mythology, the narrative that redefined him from a skilled but unremarkable practitioner into an icon. The power of branding does not lie in truth but in resonance, and in that realm, Carson triumphed. His genius, if we must grant him one, was not in the scalpel but in the art of self-mythology.

The epidemiologic trends emerging from Carson’s work are difficult to track, and therein lies the first collapse of odds. His most famous surgeries—the separation of conjoined twins—were cases that defied conventional prognostication, yet the long-term outcomes were, at best, mixed. In many of these cases, one or both twins did not survive long-term or were left with significant neurological impairments. But survival was never the point. The spectacle was the point. Carson’s genius, like that of a master illusionist, lay in the crafting of improbable narratives, not in shifting the fundamental risk landscape of pediatric neurosurgery. His career, once viewed through this lens, follows a trajectory of escalating improbabilities—each new success, however qualified, reinforcing the mythos of Gifted Hands as something ordained, inevitable. The odds did not collapse because of medical breakthroughs; they collapsed because faith in the brand made them irrelevant.

Yet, despite his medical renown, Carson’s place in history is ultimately defined by his political career, and here the brand overtook the man. In 2016, the graduating class of Hopkins Medicine demanded that the school replace Carson as their scheduled commencement speaker. By then, he was not simply a retired neurosurgeon; he was a leading candidate for the Republican nomination, the man who, however briefly, outpolled even Donald Trump in the Iowa caucuses. The moment was rich with irony: the surgeon who had built his reputation on miraculous odds-beating procedures was now the candidate selling himself as the moral conscience of the right, the quiet alternative to Trump’s bombast. But political movements do not reward quiet. The Gifted Hands narrative collapsed in the primary trenches, giving way to the coarser, more potent force of Trumpism.

Carson, however, did not vanish—he was absorbed, rebranded, made legible within the MAGA machine. Had Trump been more traditional in his racial politics, he might have offered Carson a role in Health and Human Services (HHS), a position where, ostensibly, his medical background might have had relevance. Instead, he was made Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), a post steeped in the politics of race, urban decay, and the American underclass. The move was not an accident; it was a nod to the optics of Carson’s journey—raised in poverty, the child of a struggling single mother, a Black man whose improbable rise could be weaponized to argue against systemic racism. If he could do it, why couldn’t others? The mythos of Gifted Hands had been repurposed, transformed from a Horatio Alger-style medical redemption story into a parable of conservative individualism.

But branding is a cruel master. Carson may have built his name on Gifted Hands, but history will not remember the surgeon; it will remember the cabinet member. His cadence is not that of the pioneering neurosurgeon but of the MAGA loyalist, his speeches indistinguishable from the broader rhetoric of Trump’s first term. The odds that once defined him—the boy from Detroit defying expectations to become a surgeon, the doctor taking on impossible cases—have been overshadowed by a different set of odds: those of a Black conservative rising to prominence within a movement that has, at best, a complicated relationship with race. The improbability that once made him heroic now renders him an artifact, a footnote in the broader story of Trump’s America.

The lesson in Carson’s trajectory is not about medicine but about cadence, religion, and aesthetics. The world does not remember complexity; it remembers compression. Just as Trumpism distilled American conservatism into a set of blunt, emotional slogans, Carson’s Gifted Hands has been flattened into the cadence of MAGA. His legacy is not in the children he operated on but in the speeches he gave, the policies he oversaw, the ways in which his narrative was subsumed into a larger, more potent brand. In the neural networks of our lives, in the architectures of memory and historical significance, what matters is not skill but cadence, not achievement but aesthetic optimization. And in that calculus, Gifted Hands is no longer a story about neurosurgery. It is a story about branding, about the way genius—real or imagined—is ultimately absorbed into the broader rhythms of history.

Epilogue#

Victorian mortality, in all its melodramatic flourish, never asked whether the ends justified the means. The means were already prescribed, set in stone by moralists, novelists, and bureaucrats alike. The widow must weep. The orphan must toil. The sinner must perish in regret or be redeemed at the final hour. Fate was not an open-ended question; it was an orchestrated cadence, the inevitable diminuendo before the curtain fell. Wilde saw through it. His children’s stories dismantled this contrived moral arc, revealing its hollowness, its suffocating inevitability. The selfless swallow does not ascend to eternal glory—it dies in the cold, its sacrifice absorbed into the cycle without reward. The nightingale gives its blood for art, and art does not thank it.

“I am afraid you don’t quite see the moral of the story,” remarked the Linnet.

– The Devoted Friend

Aesthetics, by contrast, does not permit such rigidity. It cannot separate the labyrinth of combinatorial search—the formless wandering of the artist, the hesitations of the poet, the missteps of the composer—from the cadence itself. There is no moral of the story, only the vast search space that precedes the resolution.

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 (Allegro) embodies this truth in sound. The left hand, voicing the chromatic wanderings of harmonic tension, weaves its way through dissonances that demand resolution but never submit outright. The right hand, tracing the familiar circle of fifths, offers the illusion of structure, but structure is merely an invitation to deviation. The genius of the piece lies in its refusal to simplify—to impose a Victorian cadence onto what is, in truth, a constantly shifting dynamic system. Each resolution carries within it the seeds of the next disruption.

This is history. This is power. This is life.

The Final Cycle#

Fig. 6 Genius: 27yo Robert Kelly. Something Dantean about this song. We have a Beatrice in Aaliyah. And a Dante in Kells. But our protagonist doesn’t quite make it beyond Purgatorio. This is the antithesis of a Victorian cadence, but not in the absurd manner of the Coen Brothers. This has a touch of gospel music, and therefore hope …#

The heir receives a world already in motion, inheriting both its constraints and its latent potential. The genius disrupts, introducing the unscripted, the unpredictable, the adversarial. The brand simplifies, compressing complexity into something digestible. The tribe iterates, reinforcing the brand, deepening its grooves into the collective psyche. And finally, religion hardens it into permanence, into faith, into an immovable structure awaiting its next reckoning.

The cycle does not end, nor does it resolve. It modulates. The tempo shifts. The orchestration changes hands. Sometimes, the heir is also the genius. Sometimes, the brand becomes the very thing it once sought to disrupt. Sometimes, the tribe outgrows the genius who gave it shape, and the religion forgets the name of the god it once worshipped.

And so, what cadence awaits? Will it be the rigid moral conclusion of the Victorian novel—the condemned revolutionary gasping out final words before the noose tightens? The tragic fall of the genius, immortalized in cautionary legend? Or the endless open-ended cadence of aesthetics, where each resolution is merely the prelude to another cycle of disruption?

The answer lies in the search space itself. The labyrinth does not end. The final cadence is only final for those who stop listening.

Ukubona#

Shaka Zulu did not die that day. The conspirators, in their haste and fear, had struck him down, but not with the finality they had intended. His body, hardened by war and sharpened by destiny, resisted death’s embrace. His breath was ragged, his vision blurred, but he was not finished. They had betrayed him, yes—but had they destroyed him? No. He drifted between realms, between fever and lucidity, his mind grasping for something beyond the pain. And then, amidst his recovery, he found it: a book, strange and foreign, carried by the white men who came with their strange tongues and sharper weapons. He could not read its words, but he did not need to. The image told him everything.

There, in fading ink, was a man broken and bleeding, nailed to wood, his ribs exposed like those of the starved, his hands stretched out not in power, but in suffering. And above his head: a crown. Not of gold, but of thorns. Shaka traced the image with his fingers. A king—dying. A man betrayed by his own people. A ruler undone not by his enemies, but by those closest to him. Shaka felt the wound at his side, still fresh. He knew this pain. His heart, like the ribs of the crucified man, had been opened not by spears but by treachery. Had he not bled for them? Had he not fought, not conquered, not taken them from dust and turned them into a nation? And this is what they did? This was his reward? He laughed, but it was a sound both bitter and knowing. This was not just a story. This was the eternal script of kings, of warriors who ascended too high, only to be pulled down by those who could not breathe in such rarefied air.

The empire that he’s built was in his imagination before it became a reality.

– Farewell

Fig. 7 This moment, at 5 hours, 56 minutes, and 44 seconds, is the very definition of “ukubona”—. To see beyond what is, to stand at the threshold of the unseen, where vision is not passive sight, but the force that bends reality to its will. It was there first —within— long before stone met stone, before hands shaped the world to match the mind.#

He sat in his weakened state, staring at the image, and then, for the first time in his life, he asked: Who is this man?

Two white men stood before him, two emissaries of a world that would soon come to press against his own. The first, a merchant, a man of coin and cunning, scoffed. “He was a Jew. Some say he was a prophet, others say he was God, but I say he was just a man. And a fool, at that. He should have stayed in his place. He should have known the world does not belong to the meek.”

The other man, a soldier, clasped his hands as if in prayer. He was of no relation to Jesus’ tribe, yet he looked at the image with something close to reverence. “He was more than a man,” he murmured. “He was the Son of God. He suffered for all, so that we might be saved. Even for those who do not believe.” He shot a glance at the merchant, who simply smirked.

Shaka considered them both, weighing their words, his mind as sharp as ever despite his wounds. “You,” he said, gesturing at the merchant. “You are of his blood, but you do not believe him?”

The merchant chuckled. “My people have seen too many messiahs to be impressed by another. He was one of many, and like all the rest, he died.”

Shaka turned to the soldier. “And you,” he said, “you are not of his people, yet you call him your king?”

The soldier nodded solemnly. “Yes.”

Shaka leaned forward, the wounds in his side protesting. His eyes flicked between them, his mind absorbing what lay beneath the surface. Here was betrayal. Here was belief. And here was a strange inversion of what should be. One rejected his own, the other embraced what was foreign. Was this not the rhythm of all things? A goat among sheep. A sheep among wolves. And he, Shaka, stood somewhere between.

Tip

Mkulu; Heir, ∂Y 🎶 ✨ 👑

Kubona; Genius, -kσ ☭⚒🥁

Betrayal; Brand, α 🔪 🩸 🐐 vs 🐑

Ubuntu; Tribe, Xβ 🎹

Nkosi; Religion, γ 😃 ⭕️

He exhaled. “This Jesus,” he said, tapping the image, “he was a king?”

“Yes,” the soldier said.

“And his people turned against him?”

“Yes.”

Shaka sat back. He had seen this before. He had lived it. And suddenly, it was not a foreign story anymore. It was not some tale from distant lands with pale-skinned men and their soft voices. It was the story of every great warrior. It was the song of Umkulu, of the heir who rose, of the genius who saw too much, of the betrayal that came like a blade in the night. But this Christ—he had been passive, had he not? He had let them take him, had he not? Shaka frowned. He was no lamb. He was a lion. And yet…

The words of his mother echoed in his mind. A leader is not a man but a spirit. A great one does not live in flesh, but in the breath of his people.

Was this why the Zulu did not fade? Because their spirit was stronger than any spear, any betrayal, any death?

He did not know if he believed in this white man’s god. But he did believe in the power of story, in the power of survival. He closed the book and rose, his body still weak but his will indomitable. His time was not yet over.

Shaka looked at the two white men and grinned. “This king,” he said, pointing to the crucified figure, “died for his people. But I have a different idea.” He turned toward the open land beyond, his land, his kingdom. “My people will not see their king fall. Not yet.”

And with that, Shaka Zulu walked into history.

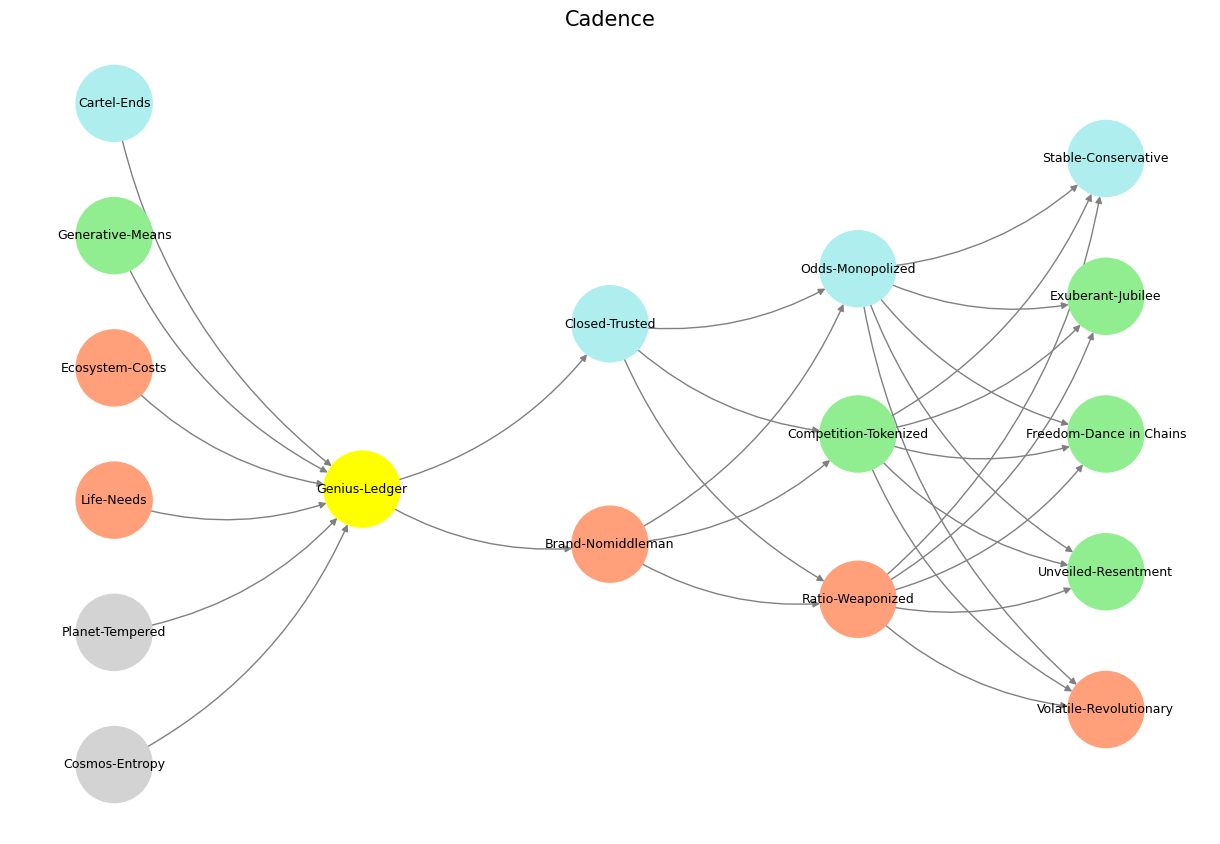

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'Planet-Tempered', 'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Generative-Means', 'Cartel-Ends', ], # Theomarchy

'Perception': ['Genius-Ledger'], # Mortals

'Agency': ['Brand-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Fire

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Gamification

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Victory

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Genius-Ledger'],

'paleturquoise': ['Cartel-Ends', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Generative-Means', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Brand-Nomiddleman',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Cadence", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 8 How now, how now? What say the citizens? Now, by the holy mother of our Lord, The citizens are mum, say not a word. Indeed, indeed. When Hercule Poirot predicts the murderer at the end of Death on the Nile, he is, in essence, predicting the “next word” given all the preceding text (a cadence). This mirrors what ChatGPT was trained to do. If the massive combinatorial search space—the compression—of vast textual data allows for such a prediction, then language itself, the accumulated symbols of humanity from the dawn of time, serves as a map of our collective trials and errors. By retracing these pathways through the labyrinth of history in compressed time—instantly—we achieve intelligence and “world knowledge.”#