(dancing-in-chains)

Dancing in Chains#

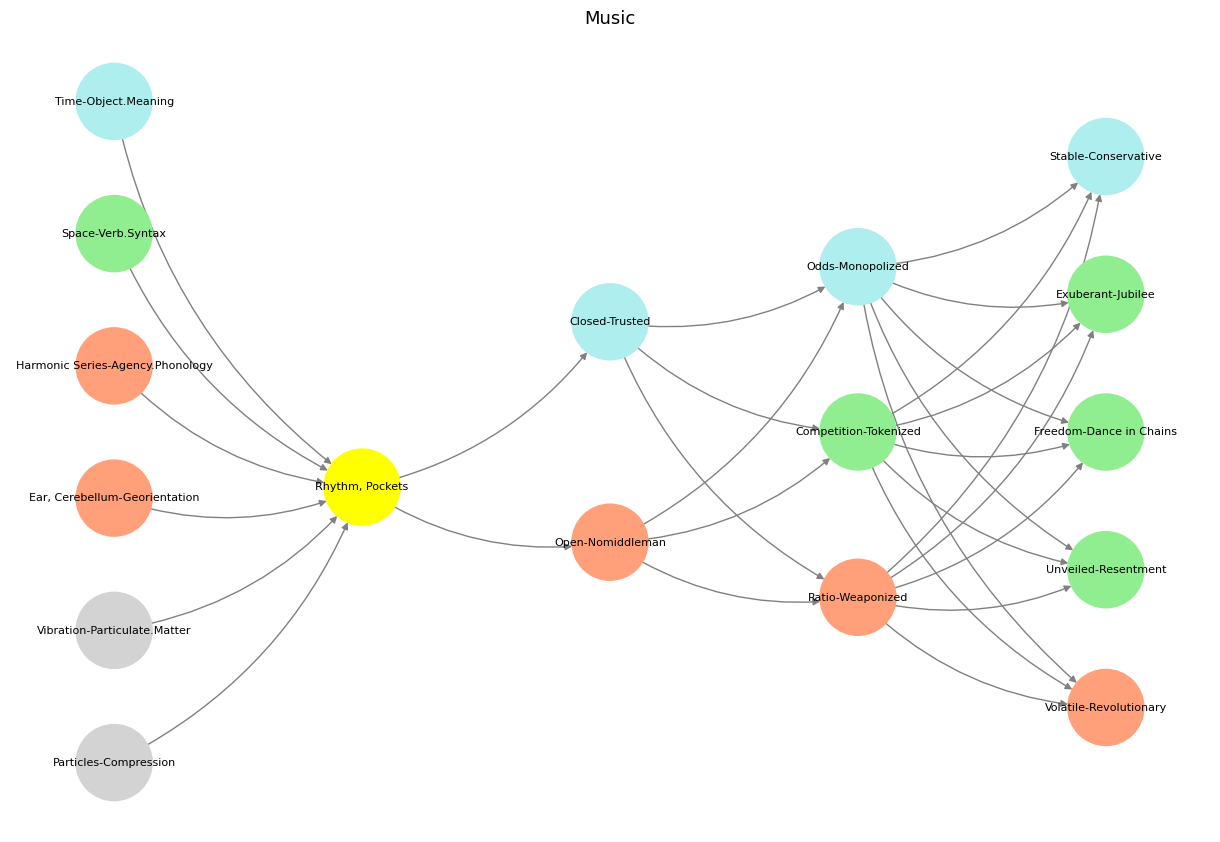

Fig. 28 Tokenization: 4 Israeli Soldiers vs. 100 Palestenian Prisoners. A ceasefire from the adversarial and transactional relations as cooperation is negotiated.#

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Particles-Compression', 'Vibration-Particulate.Matter', 'Ear, Cerebellum-Georientation', 'Harmonic Series-Agency.Phonology', 'Space-Verb.Syntax', 'Time-Object.Meaning', ], # Resources

'Perception': ['Rhythm, Pockets'], # Needs

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Costs

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Means

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Ends

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Rhythm, Pockets'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time-Object.Meaning', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Space-Verb.Syntax', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Ear, Cerebellum-Georientation', 'Harmonic Series-Agency.Phonology', 'Open-Nomiddleman',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=8, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Music", fontsize=13)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 29 G1-G3: Ganglia & N1-N5 Nuclei. These are cranial nerve, dorsal-root (G1 & G2); basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus (N1, N2, N3); and brain stem and cerebelum (N4 & N5).#