Ecosystem#

Fig. 6 Isaiah 2:2-4 is the best quoted & also misunderstood article on the conditions of social harmony. Putnams discomforts with the data tells us that he was surprised by what the UN knew half a century earlier and what our biblical prophet articulated several millenia ago. Putnam published his data set from this study in 2001 and subsequently published the full paper in 2007. Putnam has been criticized for the lag between his initial study and his publication of his article. In 2006, Putnam was quoted in the Financial Times as saying he had delayed publishing the article until he could “develop proposals to compensate for the negative effects of diversity” (quote from John Lloyd of Financial Times). In 2007, writing in City Journal, John Leo questioned whether this suppression of publication was ethical behavior for a scholar, noting that “Academics aren’t supposed to withhold negative data until they can suggest antidotes to their findings.” On the other hand, Putnam did release the data in 2001 and publicized this fact. Source: Wikipedia#

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

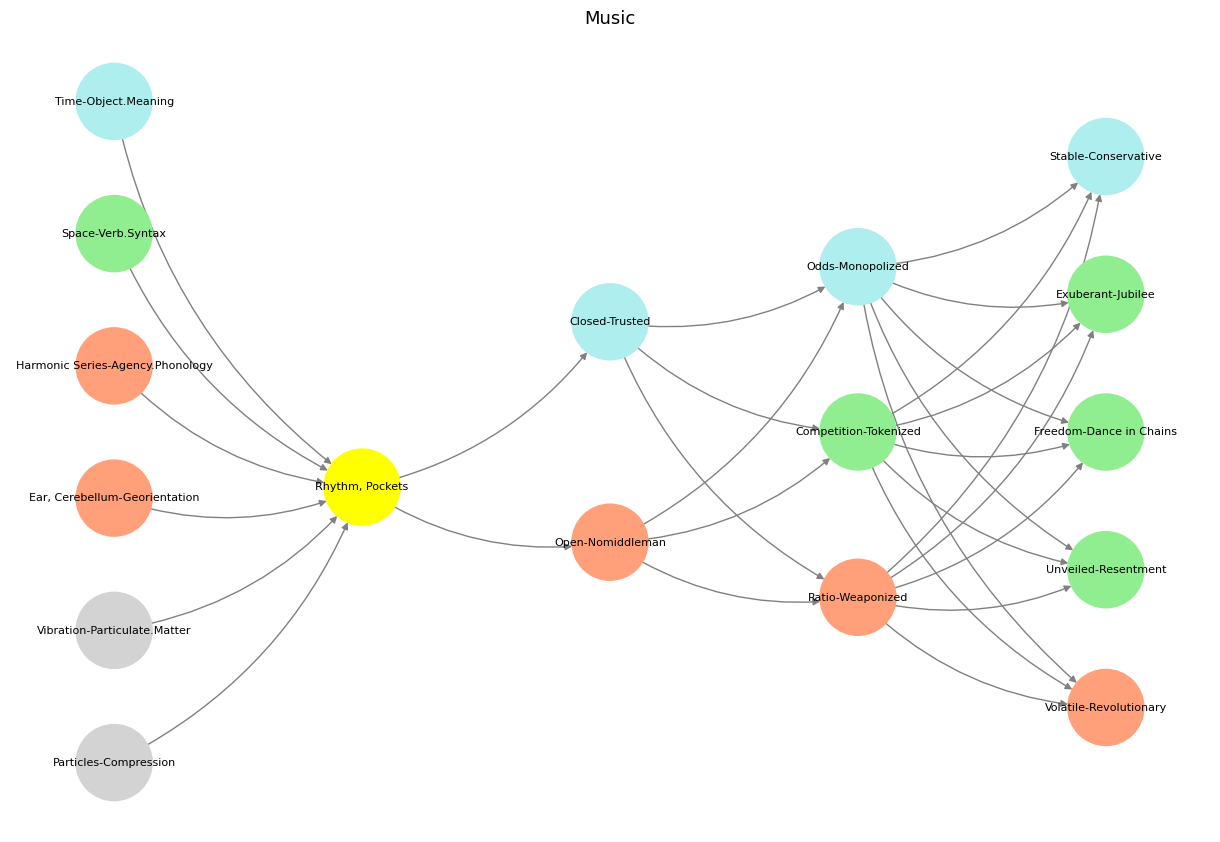

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Particles-Compression', 'Vibration-Particulate.Matter', 'Ear, Cerebellum-Georientation', 'Harmonic Series-Agency.Phonology', 'Space-Verb.Syntax', 'Time-Object.Meaning', ], # Resources

'Perception': ['Rhythm, Pockets'], # Needs

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Costs

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Means

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Ends

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Rhythm, Pockets'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time-Object.Meaning', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Space-Verb.Syntax', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Ear, Cerebellum-Georientation', 'Harmonic Series-Agency.Phonology', 'Open-Nomiddleman',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=8, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Music", fontsize=13)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 7 So we have a banking cartel, private ledgers, balancing payments, network of banks, and satisfied customer. The usurper is a public infrastructure, with open ledgers, digital trails, block-chain network, and liberated customer#