Resilience 🗡️❤️💰#

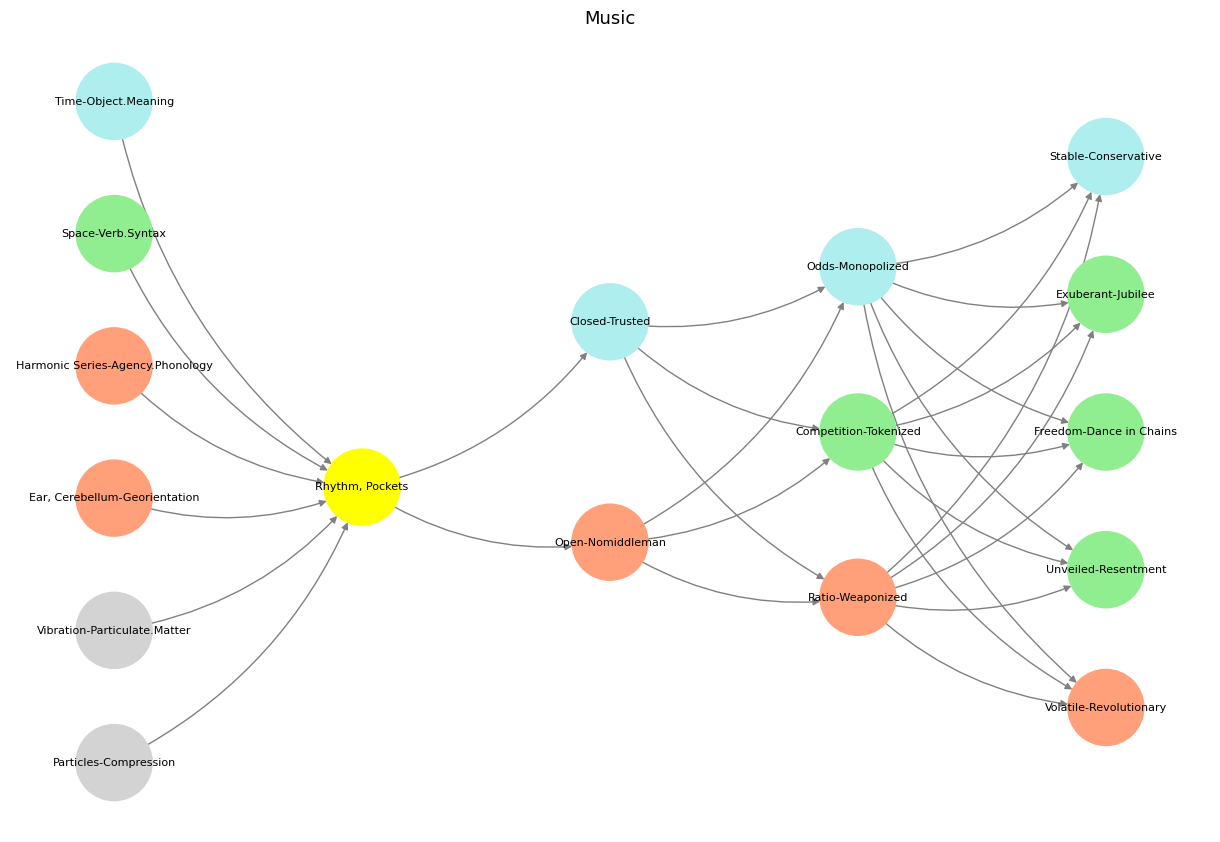

Fig. 8 Neural Anatomy of Music: What Exactly Is It About? Might it be about fixed odds, pattern recognition, leveraged agency, curtailed agency, or spoils for further play? Grants certainly are part of the spoils for further play. And perhaps bits of the other stuff.#

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Particles-Compression', 'Vibration-Particulate.Matter', 'Ear, Cerebellum-Georientation', 'Harmonic Series-Agency.Phonology', 'Space-Verb.Syntax', 'Time-Object.Meaning', ], # Resources

'Perception': ['Rhythm, Pockets'], # Needs

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Costs

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Means

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Ends

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Rhythm, Pockets'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time-Object.Meaning', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Space-Verb.Syntax', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Ear, Cerebellum-Georientation', 'Harmonic Series-Agency.Phonology', 'Open-Nomiddleman',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=8, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Music", fontsize=13)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 9 Resources, Needs, Costs, Means, Ends. This is an updated version of the script with annotations tying the neural network layers, colors, and nodes to specific moments in Vita è Bella, enhancing the connection to the film’s narrative and themes:#