Weaponized#

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network structure

def define_layers():

return {

'Pre-Input': ['Life', 'Earth', 'Cosmos', 'Sound', 'Tactful', 'Firm'],

'Yellowstone': ['G1 & G2'],

'Input': ['N4, N5', 'N1, N2, N3'],

'Hidden': ['Sympathetic', 'G3', 'Parasympathetic'],

'Output': ['Ecosystem', 'Vulnerabilities', 'AChR', 'Strengths', 'Neurons']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors(node, layer):

if node == 'G1 & G2':

return 'yellow'

if layer == 'Pre-Input' and node in ['Tactful']:

return 'lightgreen'

if layer == 'Pre-Input' and node in ['Firm']:

return 'paleturquoise'

elif layer == 'Input' and node == 'N1, N2, N3':

return 'paleturquoise'

elif layer == 'Hidden':

if node == 'Parasympathetic':

return 'paleturquoise'

elif node == 'G3':

return 'lightgreen'

elif node == 'Sympathetic':

return 'lightsalmon'

elif layer == 'Output':

if node == 'Neurons':

return 'paleturquoise'

elif node in ['Strengths', 'AChR', 'Vulnerabilities']:

return 'lightgreen'

elif node == 'Ecosystem':

return 'lightsalmon'

return 'lightsalmon' # Default color

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, center_x, offset):

layer_size = len(layer)

start_y = -(layer_size - 1) / 2 # Center the layer vertically

return [(center_x + offset, start_y + i) for i in range(layer_size)]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

center_x = 0 # Align nodes horizontally

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

y_positions = calculate_positions(nodes, center_x, offset=-len(layers) + i + 1)

for node, position in zip(nodes, y_positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(assign_colors(node, layer_name))

# Add edges (without weights)

for layer_pair in [

('Pre-Input', 'Yellowstone'), ('Yellowstone', 'Input'), ('Input', 'Hidden'), ('Hidden', 'Output')

]:

source_layer, target_layer = layer_pair

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=10, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.1"

)

plt.title("Red Queen Hypothesis", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

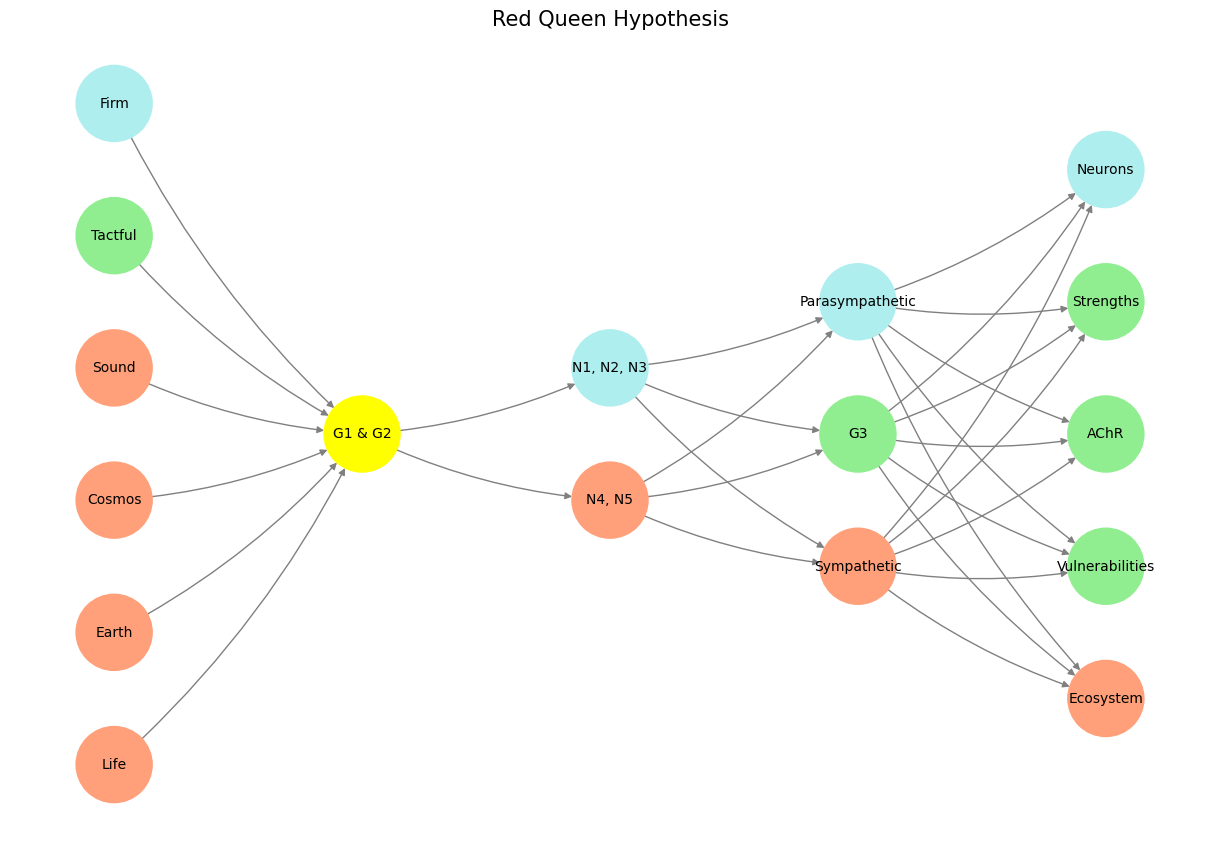

Fig. 18 Colors Match our Neural Network Model. Mental state in terms of challenge level and skill level, according to Csikszentmihalyi’s flow model. The low-skill of anxiety speaks to adversarial transformation, very dynamic in nature that one can only adapt to but never really be well trained for. By contrast, the high-skill of relaxation speaks to culturual homogeneity embodied in heritage, which most adults have mastered. Flow speaks to transactional tokenized settings, wherein rules are somewhat well established – but there’s dynamism that leaks in from adversarial settings. Imagine the neural network as the gradual rise of water in a vast, dynamic ecosystem. At the base, the red nodes pulse like molten magma, vibrant and raw, representing primal energy—the starting point of transformation. With training and calibration, this lava cools and solidifies into yellow, a symbol of emerging order, a river carving its path through the landscape. As the system learns, the water level rises, touching green nodes, which embody flourishing life and iterative growth, where stability begins to bloom amidst the chaos. The verdant hues suggest harmony, a sign that the network is finding its rhythm and the currents are smoothing over time. Finally, with near-zero error—a state of mastery and equilibrium—the system reaches the blue nodes, the serene expanse of a tranquil sea. Here, every ripple aligns, every connection hums with precision, and the water, having risen and filled the network, becomes an ocean of understanding.#