Stable#

Hearing has always been considered the most spiritual of the senses, standing apart from sight, touch, taste, and smell in its deep connection to obedience, authority, and the unseen. Across religious traditions, divine revelation comes not through sight but through hearing—Moses hears God in the burning bush, Muhammad receives the Qur’an through auditory recitation, and the Shema, the central Jewish prayer, commands, “Hear, O Israel.” Unlike vision, which requires external light and direct exposure, hearing penetrates unseen spaces, bypassing physical barriers, carrying meaning through the air itself. It is a sense that does not require the observed to be present; it transmits presence across distance, creating a bridge between self and other, between mortal and divine.

Obedience itself is derived from the Latin ob-audire, meaning “to listen attentively.” There is something in the nature of hearing that demands response, a dynamic that vision lacks. One can choose to avert their eyes, but sound—especially spoken command—invades. This may explain why authoritarian figures and divine beings alike rely on voice rather than vision to assert control. A person who hears is one who is subject to something beyond themselves, whether it be another human voice, a deity, or, in the case of schizophrenia, an internal yet foreign entity.

The phenomenon of passivity in schizophrenia, particularly the experience of auditory hallucinations, is rooted in this fundamental property of hearing. Schizophrenic voices are rarely silent observers; they are commanding, intrusive, insistent. Patients often describe voices giving orders, criticizing actions, or commenting on thoughts as though they are external authorities. This is not a visual experience—hallucinated visions, when they do occur in schizophrenia, tend to be less intrusive, more dreamlike, lacking the same compulsive force. The auditory hallucination, by contrast, demands engagement. This is why schizophrenia often manifests in the feeling that one’s will is being overtaken, that the voice is not just heard but obeyed.

This passivity is more than a symptom—it is a structural feature of how hearing functions in the brain. Unlike sight, which is spatially oriented and tied to clear focal attention, hearing is temporally fluid, requiring constant vigilance. The primary auditory cortex (BA41, BA42) and auditory association areas like BA22 in the right hemisphere are deeply connected to the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, which govern emotion and memory. This means that hearing is directly wired to the emotional centers of the brain, making it harder to resist or ignore than vision. A voice, once heard, cannot be unseen—it lingers, it demands processing, it echoes in memory, shaping perception long after it has fallen silent.

In schizophrenia, this mechanism is hyperactive. The voice is no longer an external sound source, but a self-generated one that remains externalized. It is not just heard but imposed, often in an authoritative or accusatory tone. Some researchers have linked this phenomenon to dysfunctions in the default mode network (DMN), a brain system involved in self-referential thinking and internal dialogue. When this network malfunctions, the mind misattributes its own thoughts as coming from outside sources, leading to the eerie sensation that a foreign intelligence has taken residence in one’s mind. The schizophrenic does not just hear voices—they experience obedience to them, because hearing itself is structured around submission to external authority.

This same dynamic explains why religious experiences so often involve auditory phenomena—whether in the form of spoken revelation, divine whispers, or the ineffable power of music and chant. Even outside of theology, the power of sound to induce trance, ecstasy, or surrender is evident in every human culture. The military understands this well; drill sergeants do not show images, they bark orders. Liturgical traditions, from Gregorian chant to Sufi dhikr, function through repetition of sound, bypassing rational resistance and engaging the deep auditory pathways that make obedience almost instinctual.

Hearing, then, is not merely a passive sense—it is the gateway to submission, whether to divine authority, social command, or schizophrenic delusion. The more one listens, the more one is drawn into the world of the speaker, a dynamic that can be either sacred or pathological, liberating or imprisoning. When voices originate from outside, they shape reality; when they emerge from within and are misattributed, they fracture it. This is why schizophrenia so often manifests as a disorder of hearing rather than sight. Vision allows for distance, for perspective, for choice. Hearing, once it has entered the mind, refuses to be ignored.

Fig. 35 There’s a demand for improvement, a supply of product, and agents keeping costs down through it all. However, when product-supply is manipulated to fix a price, its no different from a mob-boss fixing a fight by asking the fighter to tank. This was a fork in the road for human civilization. Our dear planet earth now becomes just but an optional resource on which we jostle for resources. By expanding to Mars, the jostle reduces for perhaps a couple of centuries of millenia. There need to be things that inspire you. Things that make you glad to wake up in the morning and say “I’m looking forward to the future.” And until then, we have gym and coffee – or perhaps gin & juice. We are going to have a golden age. One of the American values that I love is optimism. We are going to make the future good.#

Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy argues that music is the deepest, most primordial art form, a direct expression of the Dionysian spirit that transcends mere representation. It does not depict reality in the way painting or sculpture does, nor does it rely on the rigid structures of language and rational thought. Instead, music speaks to something older, something buried beneath cognition, something primal. This insight, which Nietzsche found in Greek tragedy, aligns seamlessly with the function of Brodmann’s Area 22 on the right hemisphere, which governs auditory processing, prosody, and the ineffable dimensions of meaning. If the left hemisphere, with its linguistic structures and semantic processing, is Apollonian—giving order, clarity, and meaning—then the right hemisphere’s BA22 is Dionysian, existing in a space of ambiguity, intuition, and raw emotional experience.

Schizophrenia, particularly in its auditory manifestations, can be seen as an excess of this Dionysian energy—an overactivity in the realm of pure sound and sensation that has broken free from the Apollonian structures that normally contain it. Patients who hear voices do not merely process language differently; they experience meaning outside of the usual constraints of syntax and reference. Their experience mirrors the Nietzschean claim that music, more than any other art, reveals the truth of existence as will, as force, as something beyond rational comprehension. In schizophrenia, this truth becomes overwhelming. The right BA22, in its hyperactive state, generates meaning untethered from rational discourse, producing voices that do not merely say things but demand response, much like the call of the Dionysian chorus in ancient Greek tragedy. The individual no longer commands language; language commands the individual.

This breakdown in control is not incidental but fundamental to the experience of meaning itself. Nietzsche, in his opposition to Socratic rationalism, saw in tragedy a necessary confrontation with the abyss, where meaning emerges not from rigid logic but from the willingness to surrender to forces beyond oneself. This is precisely the dynamic at play in schizophrenia’s passivity phenomenon, where individuals feel they are no longer the agent of their own thoughts but instead subject to an external force. What they experience is a kind of existential disintegration, where the structured self—the Apollonian ego—dissolves into a sea of conflicting voices and auditory hallucinations, just as the tragic chorus in Greek drama both contains and subverts the central figures of the play.

But if Nietzsche’s vision of art is to be taken seriously, this schizophrenic breakdown of meaning is not merely pathological; it reveals something essential about human existence. To exist is to be caught between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, between rational coherence and the chaotic, ineffable forces of being. If the left hemisphere’s BA22 structures words into meaning, the right BA22 suggests that meaning is something we hear rather than something we construct. This is why music—right-lateralized, free of syntax, untethered from logic—is the most existentially revealing of all the arts. It speaks to what Nietzsche called the spirit of music, the fundamental undercurrent of all tragedy, all meaning, all experience. It bypasses reason, striking directly at the core of being.

The existentialist crisis that follows from this realization is profound. If meaning is something we hear—if it is given rather than made—then what happens when that meaning becomes chaotic, uncontainable, unbearable? Schizophrenia, in its more extreme forms, embodies precisely this existential terror. It is Nietzsche’s Dionysian apocalypse brought into neurological form, where the world itself fractures into voices, where meaning becomes too abundant, too fluid, too forceful for any single self to withstand. This suggests that what we call “madness” may not be a mere malfunction of the brain but an encounter with meaning unrestrained by logic, with existence before it is ordered into coherence.

Nietzsche believed that tragedy arose when Greek culture was still able to hold the Dionysian within an Apollonian frame, allowing chaos to express itself without overwhelming the individual. But he lamented that Socratic rationalism had severed this connection, making modern humanity ill-equipped to deal with the full weight of existence. If he were alive today, he might argue that schizophrenia is a symptom not of individual disorder but of a culture that no longer knows how to mediate between rational thought and Dionysian revelation. The right BA22 continues to generate meaning—music, voices, intuitions, poetic resonances—but in the absence of a cultural structure to contain it, the individual is left to fend for themselves against an overwhelming tide of significance.

This raises the deeper existential question: Is schizophrenia merely a brain disorder, or is it a failed encounter with something real? If Nietzsche was correct that music reveals the tragic essence of existence, then perhaps the voices heard in schizophrenia are not hallucinations in the sense of being mere illusions. They are meaning itself, unstructured, unfiltered, excessive. They are what happens when the Dionysian is no longer tempered by the Apollonian, when existence is heard but not understood. And in that sense, schizophrenia might be the most honest encounter with being—one that most of us are spared only because our brains, in their Apollonian stability, refuse to let us hear.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

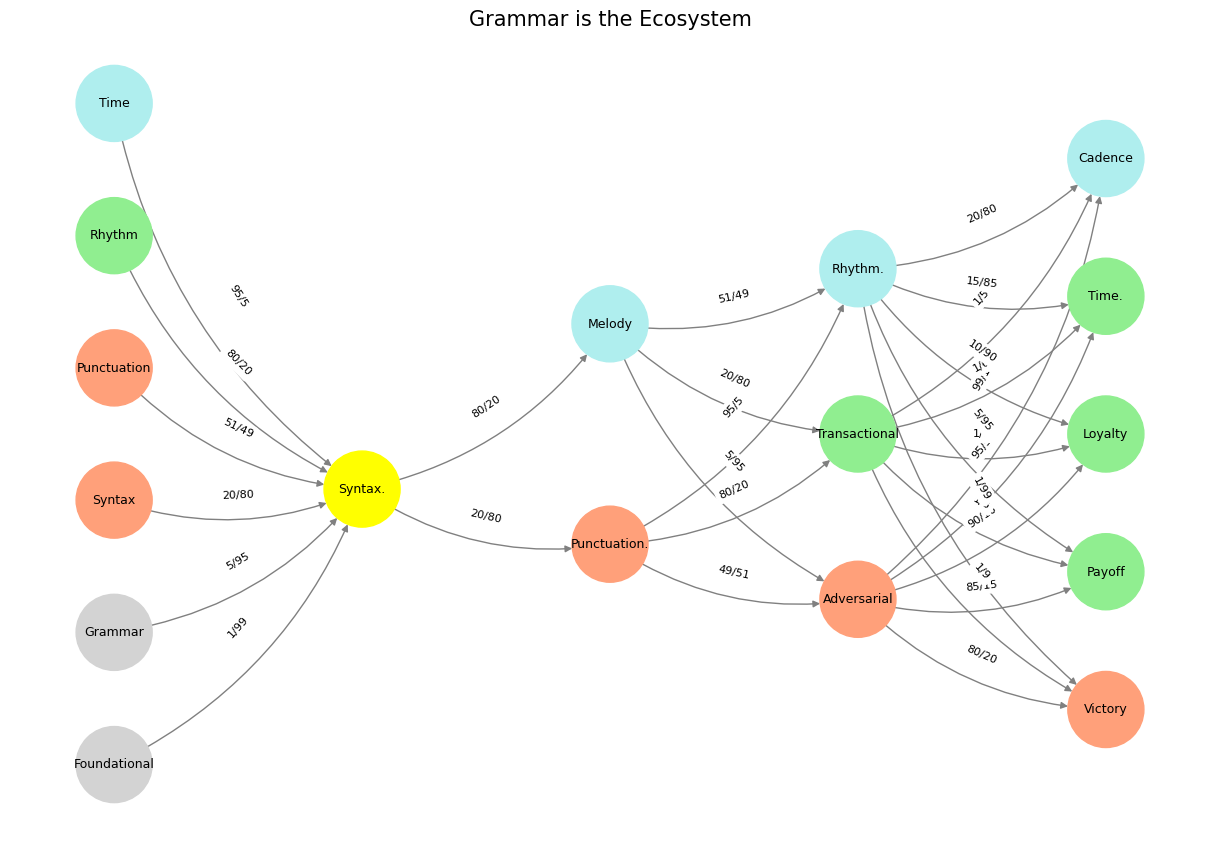

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Suis': ['Foundational', 'Grammar', 'Syntax', 'Punctuation', "Rhythm", 'Time'], # Static

'Voir': ['Syntax.'],

'Choisis': ['Punctuation.', 'Melody'],

'Deviens': ['Adversarial', 'Transactional', 'Rhythm.'],

"M'èléve": ['Victory', 'Payoff', 'Loyalty', 'Time.', 'Cadence']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Syntax.'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time', 'Melody', 'Rhythm.', 'Cadence'],

'lightgreen': ["Rhythm", 'Transactional', 'Payoff', 'Time.', 'Loyalty'],

'lightsalmon': ['Syntax', 'Punctuation', 'Punctuation.', 'Adversarial', 'Victory'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights (hardcoded for editing)

def define_edges():

return {

('Foundational', 'Syntax.'): '1/99',

('Grammar', 'Syntax.'): '5/95',

('Syntax', 'Syntax.'): '20/80',

('Punctuation', 'Syntax.'): '51/49',

("Rhythm", 'Syntax.'): '80/20',

('Time', 'Syntax.'): '95/5',

('Syntax.', 'Punctuation.'): '20/80',

('Syntax.', 'Melody'): '80/20',

('Punctuation.', 'Adversarial'): '49/51',

('Punctuation.', 'Transactional'): '80/20',

('Punctuation.', 'Rhythm.'): '95/5',

('Melody', 'Adversarial'): '5/95',

('Melody', 'Transactional'): '20/80',

('Melody', 'Rhythm.'): '51/49',

('Adversarial', 'Victory'): '80/20',

('Adversarial', 'Payoff'): '85/15',

('Adversarial', 'Loyalty'): '90/10',

('Adversarial', 'Time.'): '95/5',

('Adversarial', 'Cadence'): '99/1',

('Transactional', 'Victory'): '1/9',

('Transactional', 'Payoff'): '1/8',

('Transactional', 'Loyalty'): '1/7',

('Transactional', 'Time.'): '1/6',

('Transactional', 'Cadence'): '1/5',

('Rhythm.', 'Victory'): '1/99',

('Rhythm.', 'Payoff'): '5/95',

('Rhythm.', 'Loyalty'): '10/90',

('Rhythm.', 'Time.'): '15/85',

('Rhythm.', 'Cadence'): '20/80'

}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with weights

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in G.nodes and target in G.nodes:

G.add_edge(source, target, weight=weight)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("Grammar is the Ecosystem", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 36 Icarus represents a rapid, elegant escape from the labyrinth by transcending into the third dimension—a brilliant shortcut past the father’s meticulous, earthbound craftsmanship. Daedalus, the master architect, constructs a tortuous, enclosed structure that forces problem-solving along a constrained plane. Icarus, impatient, bypasses the entire system, opting for flight: the most immediate and efficient exit. But that’s precisely where the tragedy lies—his solution works too well, so well that he doesn’t respect its limits. The sun, often emphasized as the moralistic warning, is really just a reminder that even the most beautiful, radical solutions have constraints. Icarus doesn’t just escape; he ascends. But in doing so, he loses the ability to iterate, to adjust dynamically. His shortcut is both his liberation and his doom. The real irony? Daedalus, bound to linear problem-solving, actually survives. He flies, but conservatively. Icarus, in contrast, embodies the hubris of absolute success—skipping all iterative safeguards, assuming pure ascent is sustainable. It’s a compressed metaphor for overclocking intelligence, innovation, or even ambition without recognizing feedback loops. If you outpace the system too fast, you risk breaking the very structure that makes survival possible. It’s less about the sun and more about respecting the transition phase between escape and mastery.#