Freedom in Fetters#

Friedrich Nietzsche was right. He was right in a way that far exceeded the evidence available to him, right in a way that seems almost prescient, as if he had felt something deep within himself before science could confirm it. When he wrote The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music at the age of twenty-eight, he grasped an essential truth about human cognition, expression, and art. He saw that tragedy—and by extension, language, music, and consciousness itself—emerges from the tension between two forces: the Apollonian, structured and logical, and the Dionysian, fluid and ecstatic. He did not have Brodmann’s maps of the brain, did not have an explicit neural framework to ground his instincts, but the division he intuited aligns strikingly with what we now understand as the left and right hemispheres of the brain, specifically Brodmann’s Area 22.

Brodmann’s Area 22, part of the superior temporal gyrus, is divided between the left and right hemispheres, each governing a different dimension of language and perception. The left hemisphere, home to Wernicke’s area, processes the structured, grammatical aspects of language—the Apollonian order that ensures coherence, syntax, and intelligibility. The right hemisphere, by contrast, is responsible for prosody, for the musical and emotional contours of speech—the Dionysian wave that animates meaning beyond mere words. This anatomical division is the physiological counterpart to Nietzsche’s great insight: that human expression is never purely one or the other, that great art, great speech, great music arise from the tension between these modes of cognition.

Fig. 26 The Next Time Your Horse is Behaving Well, Sell it. The numbers in private equity don’t add up because its very much like a betting in a horse race. Too many entrants and exits for anyone to have a reliable dataset with which to estimate odds for any horse-jokey vs. the others for quinella, trifecta, superfecta#

Nietzsche was enthralled by Richard Wagner at the time of The Birth of Tragedy, and his fascination was well placed. Wagner’s operas are a total fusion of Apollonian structure and Dionysian flow, engaging both halves of Brodmann’s Area 22 to a degree few composers have ever achieved. His leitmotifs, carefully structured and interwoven, demonstrate an Apollonian mastery of musical form and coherence, while his harmonic shifts, unresolved tensions, and endless melodies spill over into a Dionysian frenzy of feeling. The very experience of listening to Wagner is an exercise in whole-brain integration—his music speaks both to the left hemisphere’s craving for structure and to the right hemisphere’s demand for transcendence. Nietzsche, in his early years, recognized this with a kind of ecstatic clarity. He believed that Wagner was reviving the lost unity of tragedy, rediscovering the synthesis of order and intoxication that had defined Aeschylus and Sophocles.

But something changed. By the time Nietzsche wrote An Attempt at Self-Criticism sixteen years later, his enthusiasm had curdled into disillusionment. He removed Out of the Spirit of Music from the title, shifting the book’s framing toward Hellenism. This change was more than editorial—it marked an intellectual and personal rupture. Nietzsche had turned against Wagner, against the man he once believed was resurrecting Dionysian energy in the modern world. His break with Wagner was not merely aesthetic but philosophical. He came to see Wagner as indulgent, decadent, a composer who, rather than uniting the Apollonian and Dionysian, had succumbed entirely to the latter, drowning in sentimentality and bombast. At the same time, Nietzsche’s understanding of Hellenism evolved. Initially, he had viewed the Greeks through the lens of Schopenhauer and Wagner—as the inventors of tragedy, the culture that balanced the Apollonian and Dionysian in its purest form. Later, he came to see classical Greece as something else: a battleground in which the Apollonian drive for clarity, reason, and order ultimately suppressed the Dionysian force of instinct and chaos. In his later years, Nietzsche came to believe that this suppression—this premature victory of Apollo—was a mistake, one that shaped the trajectory of Western thought for millennia.

In this omission, this retreat from his own insight, there is a lost opportunity. Had Nietzsche held to his original vision, had he continued to explore the tension between the Apollonian and the Dionysian rather than framing Hellenism as a stark opposition, he might have breached a frontier he only glimpsed in his youth. The Birth of Tragedy was an ecstatic, feverish work, and in some ways, it was more correct in its frenzy than in its later self-criticism. He had grasped, intuitively, that human cognition itself is structured in this dual manner, that art is a mirror of the brain, that music and language, tragedy and philosophy, all emerge from the interplay of these forces.

Yet here we are, recovering his initial insight, not as mere metaphor but as something grounded in neurophysiology. The distinction he intuited—between structure and fluidity, between clarity and intoxication—is no longer confined to aesthetics or philosophy but can be understood in terms of neural architecture. Brodmann’s Area 22, left and right, is the precise anatomical correlate of his vision. The Apollonian and Dionysian are not simply poetic abstractions; they are functions of the brain, necessary counterweights in the production of meaning itself. Language without grammar is noise; language without prosody is dead. Art without structure is chaos; art without feeling is sterile. The greatest works—whether in music, literature, or philosophy—emerge from the impossible balance between these forces.

Nietzsche’s instincts were correct. He sensed something fundamental, something that science would only later confirm. His divergence from Wagner was not necessarily a mistake—Wagner himself was a flawed vessel, his genius weighed down by his own megalomania—but Nietzsche’s turn away from his original framework, his abandonment of Out of the Spirit of Music, represents a fissure in his thought that perhaps never fully healed. Had he pursued it further, he might have found a way to integrate these forces more fully, to articulate the balance between them not just in tragedy but in cognition itself. Instead, his late works—brilliant as they are—lean more fully into the Dionysian, into the ecstatic rejection of order, into the intoxication of will and power. His youthful intuition, forged in the presence of Wagner’s music, had been tempered but also abandoned.

Yet even in that abandonment, the insight remains. The Apollonian and the Dionysian are real forces, not merely in art but in the structure of human thought. Brodmann’s Area 22, in its bifurcated function, confirms what Nietzsche knew before he could prove it. He was right, not just about tragedy, not just about Wagner, but about the way in which the human mind itself balances between the rational and the rapturous, the logical and the lyrical, the structured and the sublime. And so, through his omission, we recover his original vision—not as something lost, but as something waiting to be reawakened.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Suis': ['Foundational', 'Grammar', 'Syntax', 'Punctuation', "Rhythm", 'Time'], # Static

'Voir': ['Syntax.'],

'Choisis': ['Punctuation.', 'Melody'],

'Deviens': ['Adversarial', 'Transactional', 'Rhythm.'],

"M'èléve": ['Victory', 'Payoff', 'Loyalty', 'Time.', 'Cadence']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Syntax.'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time', 'Melody', 'Rhythm.', 'Cadence'],

'lightgreen': ["Rhythm", 'Transactional', 'Payoff', 'Time.', 'Loyalty'],

'lightsalmon': ['Syntax', 'Punctuation', 'Punctuation.', 'Adversarial', 'Victory'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights (hardcoded for editing)

def define_edges():

return {

('Foundational', 'Syntax.'): '1/99',

('Grammar', 'Syntax.'): '5/95',

('Syntax', 'Syntax.'): '20/80',

('Punctuation', 'Syntax.'): '51/49',

("Rhythm", 'Syntax.'): '80/20',

('Time', 'Syntax.'): '95/5',

('Syntax.', 'Punctuation.'): '20/80',

('Syntax.', 'Melody'): '80/20',

('Punctuation.', 'Adversarial'): '49/51',

('Punctuation.', 'Transactional'): '80/20',

('Punctuation.', 'Rhythm.'): '95/5',

('Melody', 'Adversarial'): '5/95',

('Melody', 'Transactional'): '20/80',

('Melody', 'Rhythm.'): '51/49',

('Adversarial', 'Victory'): '80/20',

('Adversarial', 'Payoff'): '85/15',

('Adversarial', 'Loyalty'): '90/10',

('Adversarial', 'Time.'): '95/5',

('Adversarial', 'Cadence'): '99/1',

('Transactional', 'Victory'): '1/9',

('Transactional', 'Payoff'): '1/8',

('Transactional', 'Loyalty'): '1/7',

('Transactional', 'Time.'): '1/6',

('Transactional', 'Cadence'): '1/5',

('Rhythm.', 'Victory'): '1/99',

('Rhythm.', 'Payoff'): '5/95',

('Rhythm.', 'Loyalty'): '10/90',

('Rhythm.', 'Time.'): '15/85',

('Rhythm.', 'Cadence'): '20/80'

}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with weights

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in G.nodes and target in G.nodes:

G.add_edge(source, target, weight=weight)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("Grammar is the Ecosystem", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

#

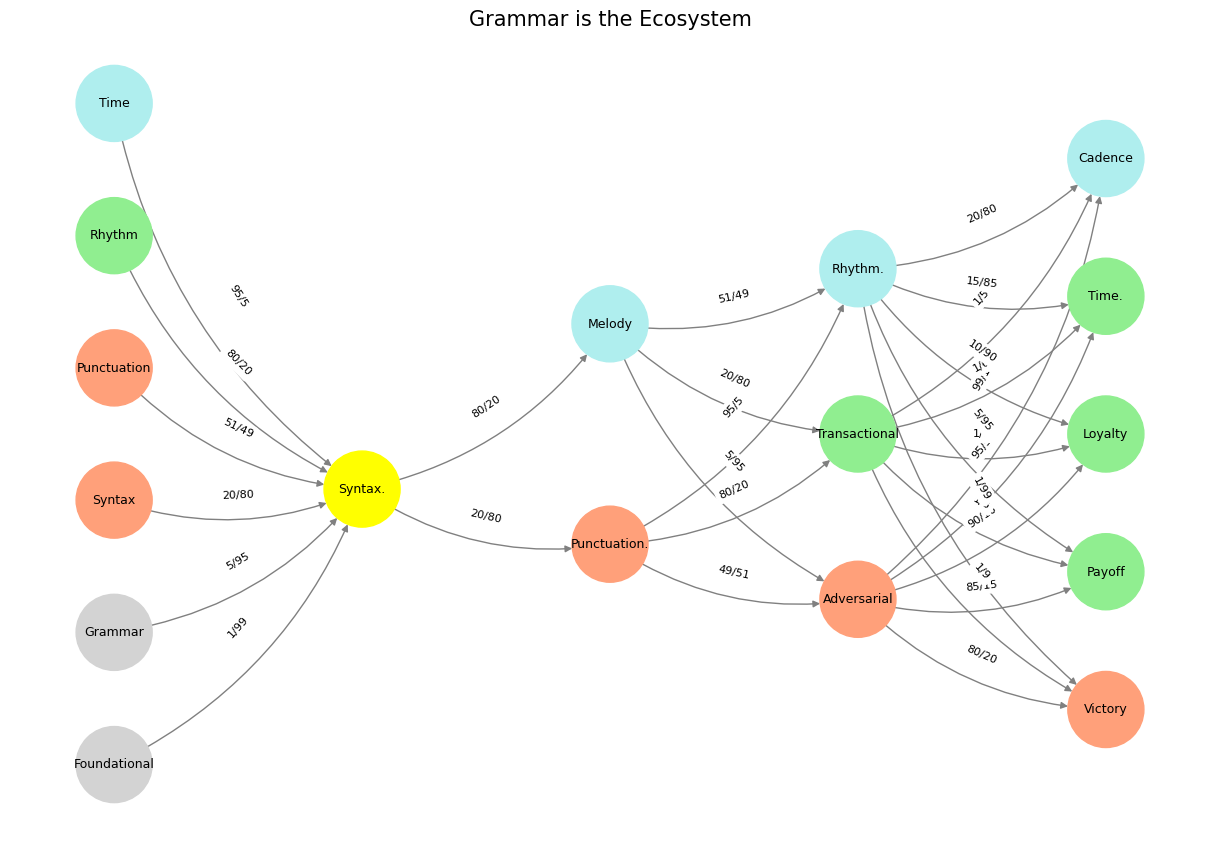

Fig. 27 From a Pianist View. Left hand voices the mode and defines harmony. Right hand voice leads freely extend and alter modal landscapes. In R&B that typically manifests as 9ths, 11ths, 13ths. Passing chords and leading notes are often chromatic in the genre. Music is evocative because it transmits information that traverses through a primeval pattern-recognizing architecture that demands a classification of what you confront as the sort for feeding & breeding or fight & flight. It’s thus a very high-risk, high-error business if successful. We may engage in pattern recognition in literature too: concluding by inspection but erroneously that his silent companion was engaged in mental composition he reflected on the pleasures derived from literature of instruction rather than of amusement as he himself had applied to the works of William Shakespeare more than once for the solution of difficult problems in imaginary or real life. Source: Ulysses#