import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

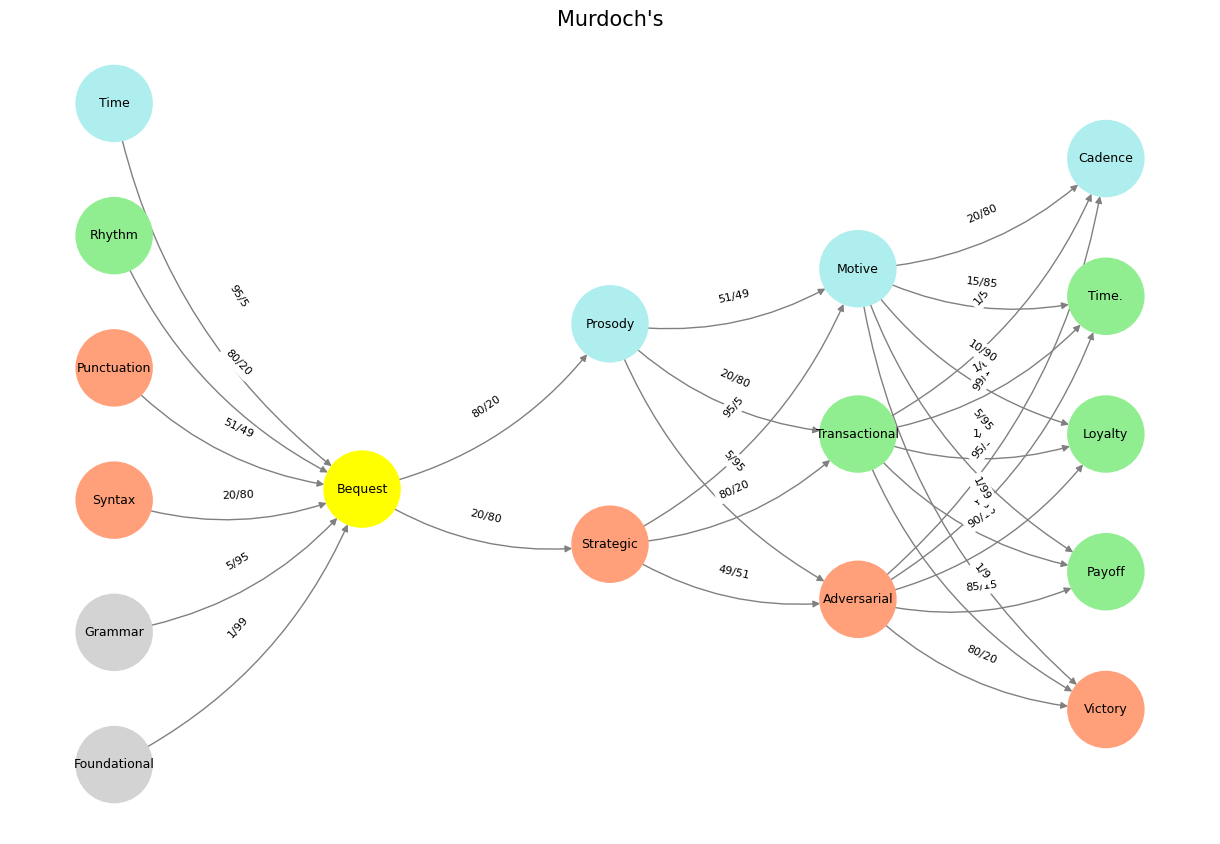

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Suis': ['Foundational', 'Grammar', 'Syntax', 'Punctuation', "Rhythm", 'Time'], # Static

'Voir': ['Bequest'],

'Choisis': ['Strategic', 'Prosody'],

'Deviens': ['Adversarial', 'Transactional', 'Motive'],

"M'èléve": ['Victory', 'Payoff', 'Loyalty', 'Time.', 'Cadence']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Bequest'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time', 'Prosody', 'Motive', 'Cadence'],

'lightgreen': ["Rhythm", 'Transactional', 'Payoff', 'Time.', 'Loyalty'],

'lightsalmon': ['Syntax', 'Punctuation', 'Strategic', 'Adversarial', 'Victory'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights (hardcoded for editing)

def define_edges():

return {

('Foundational', 'Bequest'): '1/99',

('Grammar', 'Bequest'): '5/95',

('Syntax', 'Bequest'): '20/80',

('Punctuation', 'Bequest'): '51/49',

("Rhythm", 'Bequest'): '80/20',

('Time', 'Bequest'): '95/5',

('Bequest', 'Strategic'): '20/80',

('Bequest', 'Prosody'): '80/20',

('Strategic', 'Adversarial'): '49/51',

('Strategic', 'Transactional'): '80/20',

('Strategic', 'Motive'): '95/5',

('Prosody', 'Adversarial'): '5/95',

('Prosody', 'Transactional'): '20/80',

('Prosody', 'Motive'): '51/49',

('Adversarial', 'Victory'): '80/20',

('Adversarial', 'Payoff'): '85/15',

('Adversarial', 'Loyalty'): '90/10',

('Adversarial', 'Time.'): '95/5',

('Adversarial', 'Cadence'): '99/1',

('Transactional', 'Victory'): '1/9',

('Transactional', 'Payoff'): '1/8',

('Transactional', 'Loyalty'): '1/7',

('Transactional', 'Time.'): '1/6',

('Transactional', 'Cadence'): '1/5',

('Motive', 'Victory'): '1/99',

('Motive', 'Payoff'): '5/95',

('Motive', 'Loyalty'): '10/90',

('Motive', 'Time.'): '15/85',

('Motive', 'Cadence'): '20/80'

}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with weights

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in G.nodes and target in G.nodes:

G.add_edge(source, target, weight=weight)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("Murdoch's", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()