Base#

The Elegance of Science and Art: Periodic Table and Equal Temperament#

Some ideas transform not only the domains in which they originate but ripple through the foundations of knowledge and human expression. In science, the periodic table reigns supreme, a chart that captures the essence of matter and its cosmic story. In art, equal temperament revolutionized Western music, enabling the harmonic and melodic expansiveness of symphonies and fugues. These twin pillars of understanding reflect humanity’s desire to impose order on chaos, achieving both practical mastery and profound beauty. Let us delve into their origins, their creators’ lives, and the costs and triumphs of their realization.

The Periodic Table: Dmitri Mendeleev’s Vision#

Dmitri Mendeleev, the “Father of the Periodic Table,” was born on February 8, 1834, in Verkhnie Aremzyani, a village near Tobolsk in Siberia. He was the youngest of 14 children in a family that faced severe hardships: his father went blind, and his mother had to run a glass factory to support the family. Mendeleev’s education began in Tobolsk at a local gymnasium, and after his father’s death and the family business’s failure, his mother took him to Saint Petersburg, determined to ensure he received an education. She died shortly after he enrolled at the Main Pedagogical Institute in 1850, leaving him orphaned at 16.

Mendeleev’s brilliance in chemistry emerged during his studies, but his path was far from smooth. He battled tuberculosis, suffered professional setbacks, and often struggled socially due to his unconventional ideas and personality. His pivotal work, the periodic table, was published in 1869 in his book Principles of Chemistry. It was inspired by his effort to organize the known elements and predict the properties of undiscovered ones. Famously, he arranged cards of elements with their atomic weights and properties, much like a game of solitaire, and noticed recurring patterns. His confidence in the table was vindicated as his predictions for missing elements, like gallium and germanium, proved accurate.

Mendeleev’s Flaws and Legacy

Socially, Mendeleev could be prickly. He had strained relationships with colleagues and endured scandals in his personal life. His second marriage, to a woman 30 years his junior, caused controversy and nearly cost him his academic position. Despite these imperfections, Mendeleev’s periodic table provided a framework that unified chemistry and eventually bridged physics, leading to quantum mechanics and our understanding of the universe’s elemental composition. His work, a product of empirical observation and visionary insight, continues to underpin scientific inquiry, from astrophysics to nanotechnology.

Equal Temperament: The Harmony of Sacrifice#

The history of equal temperament is more complex, involving a broader cast of characters and a more protracted evolution. The concept emerged as a solution to the imperfections of tuning systems based on the natural harmonic series. In pure intervals, pitches are determined by simple mathematical ratios (e.g., 3:2 for a perfect fifth), but stacking these intervals results in cumulative discrepancies known as the “Pythagorean comma.” Equal temperament solves this by dividing the octave into 12 equal parts, sacrificing pure intervals for a system in which all keys are equally usable.

Bach and the Well-Tempered Clavier

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (1722) is often credited with demonstrating the power of tempered tuning, but it was not strictly equal temperament. Bach employed “well temperament,” a system that allowed for the use of all keys but preserved some distinctions in their character. Equal temperament as we know it became standard only in the 19th century, facilitated by advances in instrument construction and the growing demands of composers like Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt, who required seamless modulation across all keys.

Contributors to Equal Temperament

The road to equal temperament involved figures from multiple traditions. Vincenzo Galilei, father of Galileo, wrote about the mathematical foundations of temperament in the late 16th century, while Chinese scholar Zhu Zaiyu independently described the system in 1584. The German theorist Andreas Werckmeister developed practical tuning methods in the late 17th century that laid the groundwork for Bach’s work. These contributions highlight the interconnectedness of cultures in shaping musical evolution.

Sacrifice and the Human Condition

The adoption of equal temperament was not without its costs. By tempering the natural harmonic series, it sacrificed the purity of intervals for the sake of versatility. This sacrifice echoes the archetypal theme of giving up something precious for a greater good—a motif seen in human rituals, from ancient sacrifices to modern scientific paradigms. In music, this “tragedy of compromise” enabled the rise of Western harmony, allowing composers to build symphonic and contrapuntal structures of unparalleled complexity.

Other Cultures and Microtonality#

While equal temperament dominates Western music, other cultures embrace systems that retain the nuances of microtonality. Indian classical music, with its 22 shrutis per octave, explores the expressive potential of intervals finer than those in Western scales. Chinese, Arabic, and Persian traditions similarly incorporate microtonal systems that reflect their unique aesthetic values. These systems remind us that equal temperament, while revolutionary, is not the endpoint of musical evolution but one of many ways to organize sound.

#

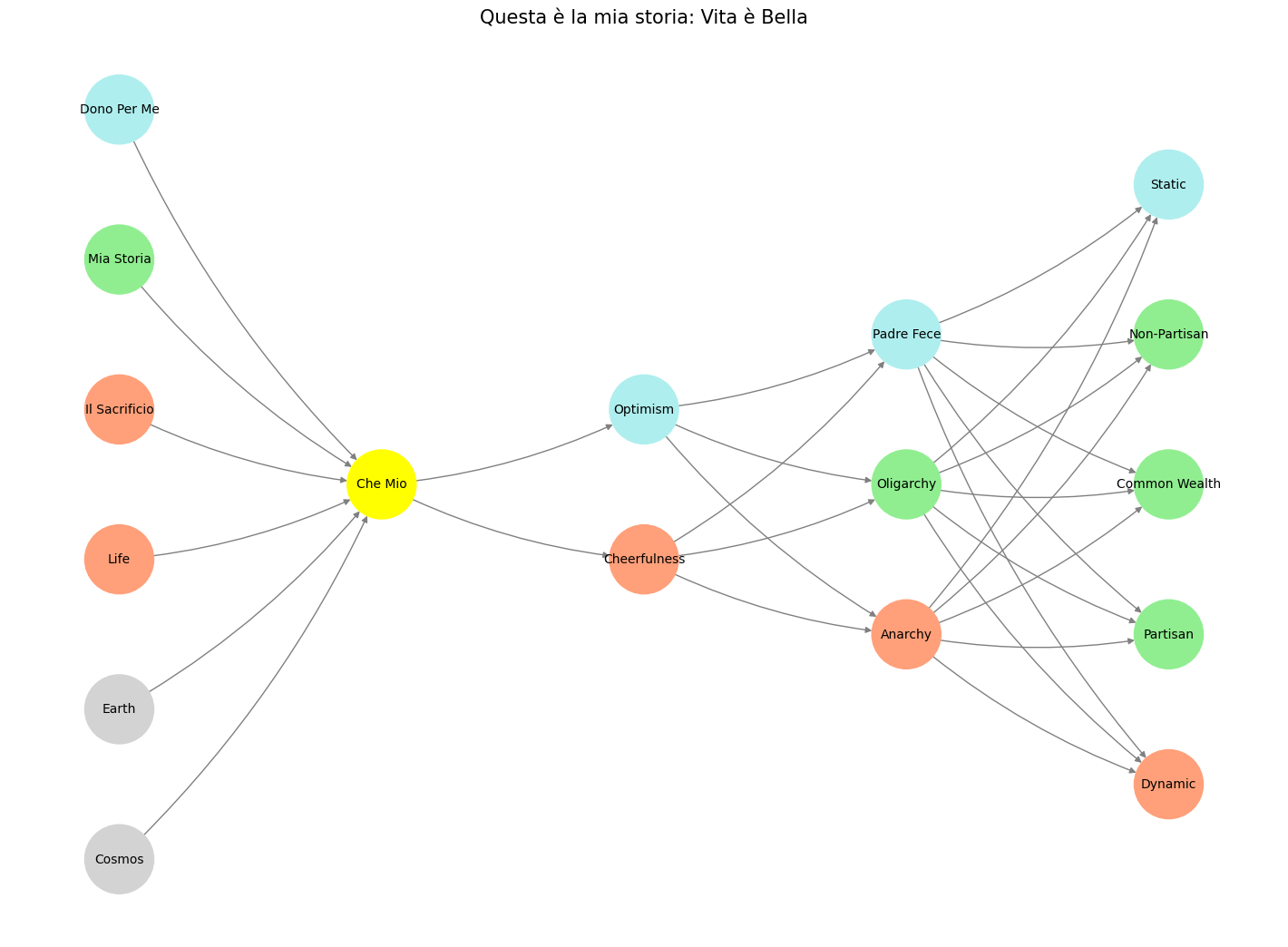

Fig. 16 From a Pianist View. Left hand voices the mode and defines harmony. Right hand voice leads freely extend and alter modal landscapes. In R&B that typically manifests as 9ths, 11ths, 13ths. Passing chords and leading notes are often chromatic in the genre. Music is evocative because it transmits information that traverses through a primeval pattern-recognizing architecture that demands a classification of what you confront as the sort for feeding & breeding or fight & flight. It’s thus a very high-risk, high-error business if successful. We may engage in pattern recognition in literature too: concluding by inspection but erroneously that his silent companion was engaged in mental composition he reflected on the pleasures derived from literature of instruction rather than of amusement as he himself had applied to the works of William Shakespeare more than once for the solution of difficult problems in imaginary or real life. Source: Ulysses#