Attribute#

In many ways, Lawrence of Arabia unfolds as a sprawling, sun-drenched sequel to the dream logic of Alice in Wonderland. The connection might seem tenuous at first glance, yet both works share a paradoxical essence: an Oxfordian embrace of absurdity and transformation. T.E. Lawrence, like Alice, tumbles into a fantastical world, one governed by rules as alien as they are immutable, where paradox becomes a form of truth, and identity is as fluid as the shifting sands. Lawrence’s story, told with the grandeur of an epic but the psychological dissonance of a fever dream, is an extension of Oxford’s hidden layer—the realm of ambiguity, compression, and emergence.

Both Lawrence and Alice begin as outsiders to their new worlds. Lawrence’s arrival in Arabia mirrors Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole. Arabia, like Wonderland, is governed by its own surreal logic, where tribal allegiances, desert etiquette, and the mirage-like nature of power dictate survival. The absurdity of Arabia’s internal rules—a vast expanse with rigid traditions and sudden, violent shifts—reflects the unpredictable, often nonsensical dynamics of Wonderland. And yet, Lawrence, like Alice, learns to navigate this realm with a mix of Oxfordian virtues: firmness, tact, and soundness.

Firmness in Lawrence’s character manifests as his unyielding commitment to his adopted identity. Where Alice dons and sheds roles in Wonderland, from chess piece to jury member, Lawrence embodies his transformations so fully that the boundary between T.E. Lawrence and the legendary “Loras of Arabia” begins to blur. This self-reinvention, though outwardly pragmatic, echoes the Oxfordian resolve to maintain the integrity of the game, even when the game itself defies conventional reason. Lawrence’s insistence on donning Arab robes, on mastering the language and customs, is not merely adaptation but a deliberate act of becoming—a firmness of identity that borders on the surreal.

Tact, too, defines Lawrence’s passage through this desert Wonderland. His ability to manipulate circumstances without ever fully revealing his own motives is a hallmark of Oxfordian maneuvering. Much like the Cheshire Cat’s cryptic smiles or the civil servants in Yes Minister, Lawrence operates within a dreamscape where direct confrontation is rarely effective. His victories are subtle and paradoxical: he persuades without commanding, leads by allowing others to feel they are in control. His finest moments, whether uniting warring tribes or orchestrating the impossible assault on Aqaba, are acts of tactful absurdity—improbable outcomes that feel, in hindsight, inevitable within the dream-logic of Arabia.

But it is soundness that most firmly ties Lawrence to Wonderland. The internal consistency of his world—the mirage of coherence he maintains—sustains both his myth and his sanity in the face of overwhelming contradictions. Much like Oxford’s reverence for the absurd, Lawrence’s legend depends on his ability to impose a kind of poetic order on chaos. His writings in Seven Pillars of Wisdom are not dry records of military campaigns but lyrical explorations of identity, purpose, and the surreal beauty of the desert. Lawrence, like the Mad Hatter or the Queen of Hearts, understands that soundness lies not in objective truth but in the preservation of a system’s internal logic. The desert, with its mirages and shifting sands, becomes a metaphor for this oxymoronic stability.

Irony, of course, threads through both Lawrence’s and Alice’s stories, much as it does through the works of another Oxford wit, Oscar Wilde. Lawrence’s transformation into “Loras of Arabia” is riddled with Wildean irony: the man who claims he fights for Arab independence ends up a reluctant agent of British imperialism. This tension—between the ideal and the real, the mythic and the mundane—is as sharp as Wilde’s epigrams. Lawrence’s life, like a Wildean play, is a series of ironic inversions: the hero who despises war but becomes its master tactician, the outsider who is both embraced and alienated by the culture he adopts, the man who seeks anonymity but becomes a legend. Wilde would have appreciated the tragic comedy of Lawrence’s predicament, a figure so consumed by his own myth that he becomes its prisoner.

Oxford, as the shared birthplace of these tales, binds their absurdities together. Dodgson’s Wonderland, Wilde’s drawing-room paradoxes, and Lawrence’s desert mirages all emerge from the same hidden layer of England’s intellectual tradition. Oxford revels in ambiguity, in the slipperiness of meaning, and in the transformative power of paradox. It is a place where rules are made to be inverted, where identities are masks to be donned and discarded, and where the absurd becomes a kind of higher truth.

Ultimately, Lawrence’s story is not so different from Alice’s. Both are tales of transformation, of journeys through surreal landscapes governed by their own peculiar logics. Both protagonists emerge changed, yet fundamentally alone—Alice, waking from her dream to find herself a stranger in her own home, and Lawrence, retreating into obscurity, his myth larger than the man could ever be. If Cambridge is the input layer, the realm of immutable truths, then Oxford is the hidden layer, where those truths are compressed, inverted, and transformed into the emergent complexities of human experience. Lawrence of Arabia, like Alice in Wonderland, is Oxfordian to its core: a dreamlike odyssey where paradox reigns, identity shifts, and the absurd becomes the stage for human greatness—and folly.

Show code cell source

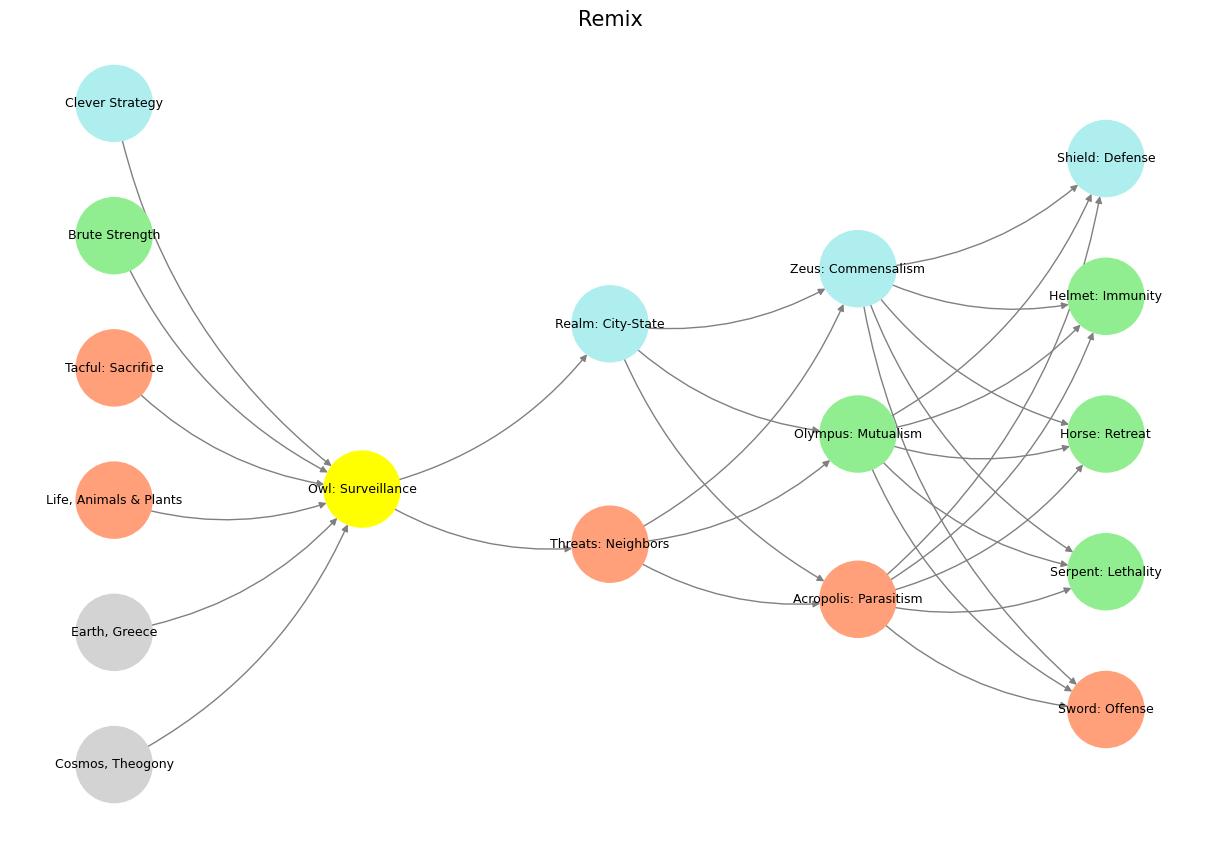

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network structure

def define_layers():

return {

'World': [

'Cosmos, Theogony', 'Earth, Greece', 'Life, Animals & Plants',

'Tacful: Sacrifice', 'Brute Strength', 'Clever Strategy'

],

'Perception': ['Owl: Surveillance'],

'Agency': ['Threats: Neighbors', 'Realm: City-State'],

'Generativity': [

'Acropolis: Parasitism', 'Olympus: Mutualism', 'Zeus: Commensalism'

],

'Physicality': [

'Sword: Offense', 'Serpent: Lethality', 'Horse: Retreat',

'Helmet: Immunity', 'Shield: Defense'

]

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Owl: Surveillance'],

'paleturquoise': [

'Clever Strategy', 'Realm: City-State', 'Zeus: Commensalism',

'Shield: Defense'

],

'lightgreen': [

'Brute Strength', 'Olympus: Mutualism', 'Helmet: Immunity',

'Horse: Retreat', 'Serpent: Lethality'

],

'lightsalmon': [

'CosmosX, Theogony', 'EarthX, Greece', 'Life, Animals & Plants',

'Tacful: Sacrifice', 'Acropolis: Parasitism', 'Sword: Offense',

'Threats: Neighbors'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Remix", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 25 Glenn Gould and Leonard Bernstein famously disagreed over the tempo and interpretation of Brahms’ First Piano Concerto during a 1962 New York Philharmonic concert, where Bernstein, conducting, publicly distanced himself from Gould’s significantly slower-paced interpretation before the performance began, expressing his disagreement with the unconventional approach while still allowing Gould to perform it as planned; this event is considered one of the most controversial moments in classical music history.#