Engineering#

“If you knew Time as well as I do,” said the Hatter, “you wouldn’t talk about wasting it. It’s him.”

– Hatter

Title: “The Compounding Squirrel: Lessons in Nuts, Neural Networks, and Neglect”#

Opening: The Squirrel and the Neural Network#

Picture a squirrel, scampering through the summer and fall, tirelessly hoarding nuts. It doesn’t question the process, doesn’t pause to revel in the bounty it’s amassed, and certainly doesn’t connect the dots about whether it will actually find those nuts come winter. The squirrel is nature’s accidental economist, a walking neural network designed to master the art of compounding—and misplacing.

But what does this have to do with us, you ask? Everything. Because, like the squirrel, we humans are caught in the glorious chaos of compounding—whether it’s wealth, wisdom, or worries.

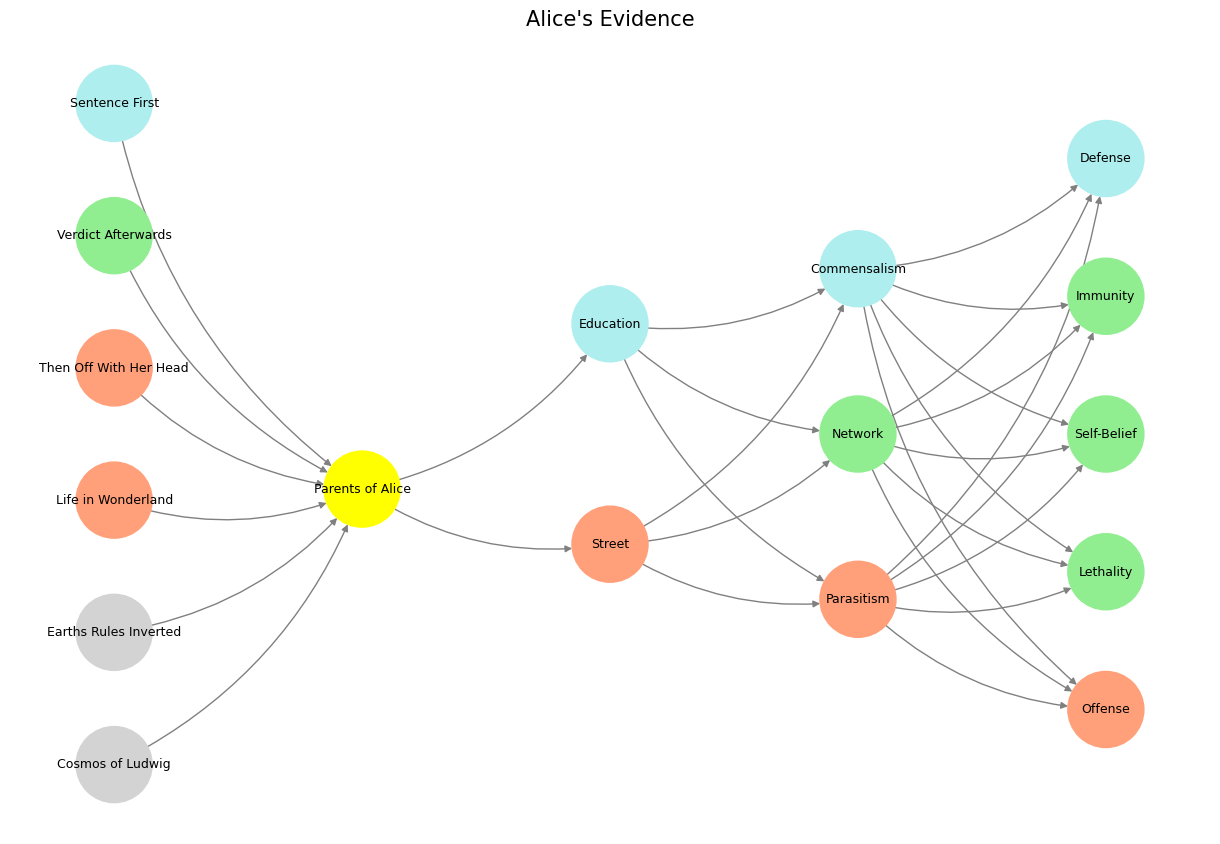

Fig. 13 Leveraged Agency. At Championship-level, tactical approaches aren’t going to win you the trophy. The odds here are 1000/1 or longer and can’t be collapsed, given the numerous entrants and exists each year – similar to what we witnessed in leveraged agency sort of games like horse-racing. The higher the risk, higher the error, because no amount of analysis can ever utilize the most up-to-date dataset when the very populations of study are so dynamic.#

Compounding 101: A Squirrel’s Guide#

1. Summer Hustle, Fall Grind#

The squirrel starts with a single nut, but by mid-fall, it has amassed enough to build a modest hedge fund. It’s the Warren Buffett of rodents—compounding tirelessly. But unlike us, it doesn’t procrastinate. No, the squirrel is a neural network of efficiency:

Input Layer: Sight, smell, and sheer paranoia.

Hidden Layer: Where to hide the nut? Behind a tree, in the ground, or in someone’s attic?

Output Layer: Nut hidden. Repeat.

And yet, despite this remarkable instinct, the squirrel faces a tragic truth: compounding only works if you can actually retrieve what you’ve accumulated. Sound familiar? Ever lose a password to your crypto wallet?

2. Winter: The Great Retrieval Problem#

Squirrels, it turns out, lose an estimated 74% of their hoarded nuts to forgetfulness, theft, or—worst of all—other squirrels. The compounding they’ve achieved doesn’t just benefit them; it inadvertently feeds the entire ecosystem. It’s socialism, squirrel-style, where even freeloaders profit.

And here lies the grand lesson for us humans: compounding doesn’t just create wealth or resources—it also creates complexity. The more you have, the harder it is to manage.

Neural Networks: Compounding for Humans#

Now, let’s translate the squirrel’s saga into human terms, via the lens of Ayesha Ofori’s backpropagation model:

Inheritance: Like a squirrel born into a nut-dense forest, some humans start with an inheritance—a launchpad for compounding.

World View: Your perception layer. Should you focus on hoarding, spending, or both?

Decisions: Every nut you hide—or investment you make—is a decision node in your network.

Exposure: Unlike squirrels, humans have to decide how much risk they’ll tolerate. For squirrels, every winter is an existential threat. For humans, it’s inflation, recession, or FOMO.

Launchpad: The retrieval phase. Will your compounded efforts actually lead to generational wealth, or will they be scattered by forces beyond your control?

Humorously Practical Takeaways: Squirrel Wisdom for Winter#

Don’t Over-Hoard: If a squirrel can lose 74% of its nuts, imagine what humans lose by overcomplicating things. Simplicity compounds better than complexity.

Invest in Retrieval: A squirrel might benefit from GPS tagging its nuts; you might benefit from organizing your retirement plan (or at least writing down your passwords).

Share the Wealth: When you can’t enjoy everything you’ve amassed, maybe it’s time to distribute the surplus. Squirrels don’t plan this, but their forgetfulness feeds entire forests. Your generosity can do the same.

Closing: A Squirrel’s Retrospective#

By winter’s end, the squirrel sits atop a snow-covered branch, gnawing on one of the few nuts it managed to retrieve. It has no idea how many it hid, lost, or gave away unintentionally. But here’s the kicker: the squirrel still survives, and the forest it lives in thrives, all thanks to compounding.

So, next time you’re building wealth, launching a neural network, or hiding metaphorical nuts, remember the humble squirrel. Compounding is powerful, but it’s not just about what you gain—it’s about what you can actually use, and how much good your efforts leave behind.

Let’s hope we can all find our nuts when it matters most.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network structure

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos of Ludwig', 'Earths Rules Inverted', 'Life in Wonderland', 'Then Off With Her Head', 'Verdict Afterwards', 'Sentence First', ],

'Perception': ['Parents of Alice'],

'Agency': ['Street', 'Education'],

'Generativity': ['Parasitism', 'Network', 'Commensalism'],

'Physicality': ['Offense', 'Lethality', 'Self-Belief', 'Immunity', 'Defense']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Parents of Alice'],

'paleturquoise': ['Sentence First', 'Education', 'Commensalism', 'Defense'],

'lightgreen': ['Verdict Afterwards', 'Network', 'Immunity', 'Self-Belief', 'Lethality'],

'lightsalmon': ['Life in Wonderland', 'Then Off With Her Head', 'Street', 'Parasitism', 'Offense'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Alice's Evidence", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 14 Tryptophan, Tryptamine, and Y’all Who Be Trippin’. Information in nature is encoded in gravity and photons and zapped from the cosmos, to earth, to life, to silicon. As for the point of view, thats open for discourse. Source: Lorenzo Expeditions. And if we invert all the aforementioned, then we might say something like: The code provides a unique blend of art and science, creating a visual narrative that might engage viewers in thinking about the structure of thought, decision-making, or the whimsical nature of reality as depicted in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” - Grok-2.#