Failure#

Engaging with Modern Processes: A Model for Living Kidney Donation and Beyond

In an age where processes have grown to unfathomable complexity, alienating individuals from the systems that shape their lives, the key to re-engagement lies in understanding and participating in these processes. As Charlie Chaplin depicted in Modern Times, individuals can feel reduced to mere cogs in vast, impersonal machinery. To counter this, engagement requires knowledge of the process itself, even as these processes become increasingly opaque due to specialization, departmental silos, and the optimization of discrete nodes within sprawling systems.

The living kidney donation process offers a powerful microcosm of this broader phenomenon. It begins with the donor referral, often rooted in a cooperative context—such as donating to a family member or friend—or as a token of altruistic values, where the donor volunteers for anyone in need. In rare adversarial instances, like a mob boss coercing an underling to donate, the process is manipulated by external forces. Yet, irrespective of context, the system’s first task is eligibility determination—a critical gatekeeper function analogous to the “yellow node” in a neural network.

This eligibility decision involves evaluating the donor through a sophisticated interface driven by beta coefficients and covariance matrices. The donor interacts with this interface by entering their demographic and evaluation data or using default assumptions where information is incomplete. The result is an interactive tool overlaying Kaplan-Meier survival curves: projections for perioperative mortality, 30-year overall mortality, and 30-year risk of kidney failure, both with and without nephrectomy. These curves, bounded by 95% confidence intervals, provide a personalized risk assessment. For younger donors, the estimates are precise; for older donors, wider confidence intervals highlight the uncertainty inherent in their projections.

Once informed, the donor chooses to proceed or withdraw, exercising agency at the third layer. This decision is followed by the fourth layer, where the physiological changes post-nephrectomy are modeled as a black box for now. Future iterations could decode this layer, but for the present, it is treated as unknown. Finally, the fifth layer aims to optimize outcomes. Crucially, the metric to optimize is not raw perioperative mortality but attributable risk—the difference in outcomes between donors and a matched control group. Without this distinction, models risk optimizing irrelevant or impossible outcomes, such as attributing zero mortality to nephrectomy even when external factors like homicide or accidents occur.

This layered framework resonates with Athena’s symbolism: her spear represents precision in optimizing attributable risks, her shield embodies ethical safeguards against unnecessary harm, and her serpent suggests the wisdom of iterative refinement. The retreating horse signifies the humility to acknowledge uncertainty and adjust accordingly. By optimizing the correct metrics and acknowledging limitations, this model not only advances medicine but offers a blueprint for engaging with other complex systems.

Beyond kidney donation, this framework generalizes to all decision-making processes in human life. Students can be introduced to this system through interactive apps, fostering fascination and understanding. By reverse-engineering these tools, they learn the backend processes: HTML, JavaScript, and the statistical foundations behind the coefficients and matrices. This leads them to regression analysis, scripting workflows in Python or R, and collaborating with data guardians. The output—covariance matrices and calculated risks—serves as a justification for IRB approval and access to broader datasets. This iterative process ensures efficiency, ethical transparency, and a clear understanding of disclosure risks.

As students progress, they transition from collaborators to principal investigators, mastering the system in a coherent and beautiful manner. This networked approach integrates ethics, relationships, and technical skills, cultivating a new generation of scholars and practitioners deeply engaged with the systems they inhabit. By understanding the processes, they transform from passive participants into active, informed agents of change, bridging the gap between human agency and the vast machinery of modern life. This model, with its layers of engagement, optimization, and iteration, becomes not just a tool for kidney donation but a universal framework for navigating complexity.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

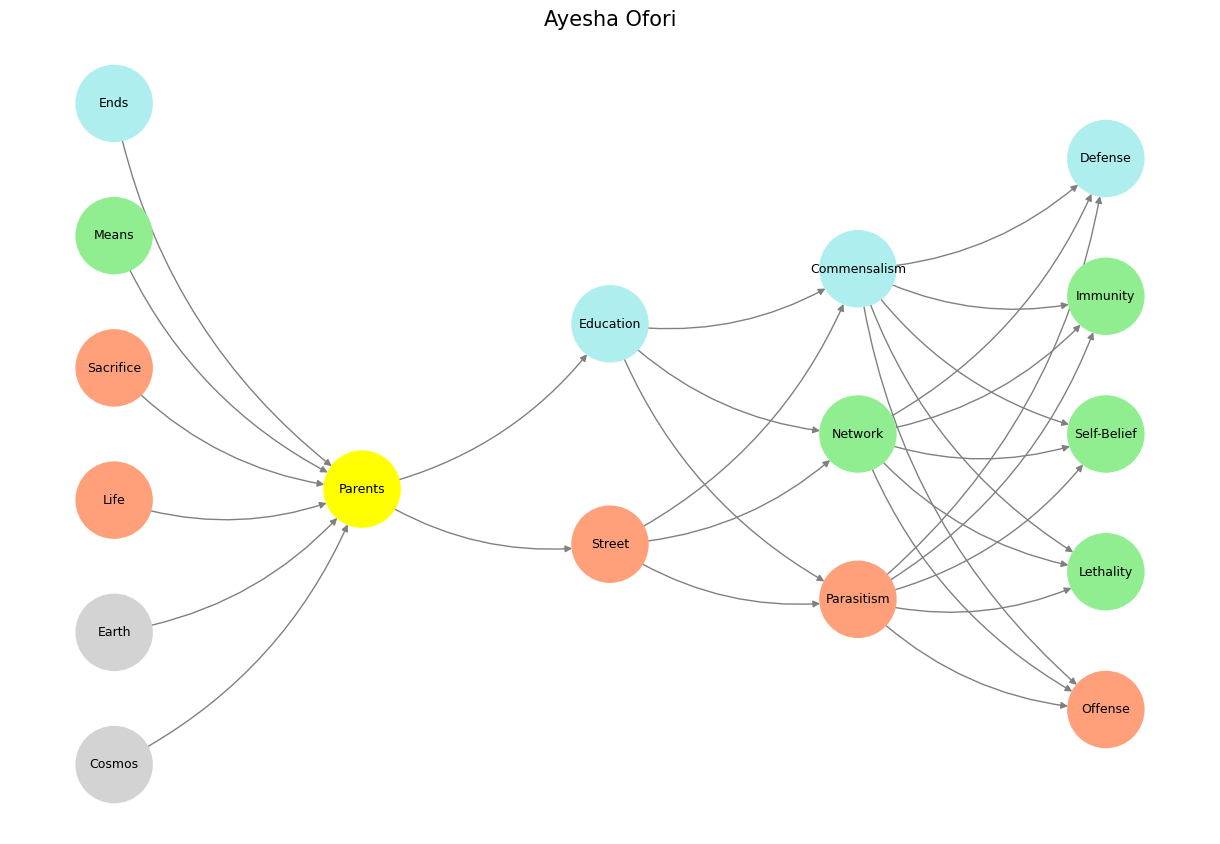

# Define the neural network structure

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos', 'Earth', 'Life', 'Sacrifice', 'Means', 'Ends', ],

'Perception': ['Parents'],

'Agency': ['Street', 'Education'],

'Generativity': ['Parasitism', 'Network', 'Commensalism'],

'Physicality': ['Offense', 'Lethality', 'Self-Belief', 'Immunity', 'Defense']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Parents'],

'paleturquoise': ['Ends', 'Education', 'Commensalism', 'Defense'],

'lightgreen': ['Means', 'Network', 'Immunity', 'Self-Belief', 'Lethality'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Life', 'Sacrifice', 'Street',

'Parasitism', 'Offense'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Ayesha Ofori", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 21 He invented the acronym “SMI²LE” as a succinct summary of his pre-transhumanist agenda: SM (Space Migration) + I² (intelligence increase) + LE (Life extension). Interesting ideas since they align with the elements of machine learning: a massive combinatorial search space, clear function to optimize, a lot of data and/or simulation. Space migration literally touches on search space, although it isn’t quite a combinatorial sort. Intelligence increase arises from time-compression through parallel processing the trial-error navigation of a massive combinatorial space, while minimizing error through feedback and iteration. With time-compression wisdom emerges, which makes life extension possible.#