Dancing in Chains#

Idiomatic speech is often understood as a manner of expression that is natural to a native speaker, encompassing common phrases, colloquialisms, and syntactical patterns that distinguish a language’s organic flow from its mechanical or formal structures. However, idiomatic speech is more than just text; it emerges from a deeper confluence of auditory memory, rhythmic conditioning, and melodic association that begins in infancy. A child does not learn a language merely through words but through the tonal and rhythmic contours that carry those words. This process is fundamentally musical—language acquisition is, in essence, an initiation into an auditory landscape, where meaning is embedded not only in vocabulary but also in pitch, cadence, and dynamic shifts in tone.

A child growing up in a language environment absorbs more than just words; they internalize the entire phonetic ecosystem that accompanies speech. The French expression c’est ce qu’on a suivi toute l’enfance captures this well: a child follows, traces, and unconsciously maps the contours of their native tongue long before they can articulate it themselves. Thinking itself is auditory before it becomes textual. This is why language acquisition for a hearing child is deeply intertwined with melody and rhythm—before meaning is grasped through individual words, it is felt through intonation, rise and fall, and the subtle modulations that signal comfort, authority, invitation, or reprimand. This is why a child instinctively knows the difference between an adversarial command, a cooperative reassurance, and a transactional request long before they can explain what these differences mean.

Fig. 31 Inheritence, Heir, Brand, Tribe, Religion. Karoline Leavitt’s voice has a melody, rhythm, timing, and cadence that is comparable to a fledgling pianists first recital. It’s not idiomatic, doesn’t flow, and talking points are repeated in overplus. She’s following a prompt.#

Idiomatic speech, then, is not just a static collection of expressions but a living, adaptive musical system in which pitch and rhythm correlate with social functions. The adversarial mode of speech—commanding, cutting, often staccato—has its own characteristic rhythms, as does the cooperative mode, which tends to be softer, more fluid, and melodic. The transactional mode, found in commercial exchanges, bureaucratic settings, or instructional contexts, has its own cadence—efficient, clipped, and rhythmically predictable. These patterns are deeply ingrained and exist across cultures, though their specific manifestations vary. A child exposed only to a transactional linguistic environment—such as learning a language in adulthood primarily for business purposes—will struggle to access the full idiomatic range because they lack exposure to the cadences that emerge in childhood play, nursery rhymes, familial comfort, and even the lilting tones of storytelling.

This complexity extends to the higher-order difficulty of replicating the musicality of language. Accents, for example, are not merely a matter of pronunciation but of rhythm and melody. This is why it is easier to learn vocabulary than to adopt a truly native-like accent—because the accent is an imprint of a lifetime’s worth of exposure to the shifts in pitch and cadence that define a speech community. The aristocratic British accent, often characterized by its suppression of vowels and clipped consonants, carries a particular rhythm that signals status and detachment. Shakespeare’s language, though textual in its legacy, was once performed with an oral richness that modern audiences often miss—each production of Hamlet or Macbeth carries a different inflection, and whether one aligns or clashes with a director’s interpretation depends on one’s own auditory expectations formed over a lifetime.

This brings us to a fundamental connection between language and music: idiomatic speech is, at its core, a musical phenomenon, and one’s capacity to connect with a language’s musicality is deeply tied to one’s early exposure to its rhythms. This is why folk music remains largely inaccessible to those outside its native culture. Folk traditions are not just about lyrics and melodies; they encode a culture’s specific rhythmic logic, the cadences of daily speech, the pauses, the accelerations, the emphases that are second nature to those who grew up immersed in them. For someone raised outside of a folk tradition, even technical mastery of the notes may not bridge the gap because the deeper cultural and linguistic rhythm is absent. The exceptions to this often involve historical power imbalances—where colonial domination imposed not only linguistic but also musical enculturation, stripping individuals of their original idiomatic frameworks and replacing them with a foreign one. Under such conditions, entire populations were forcibly reoriented toward the rhythms, cadences, and harmonies of the dominant culture, creating a complex, sometimes uneasy fusion of musical and linguistic identities.

This difficulty in replicating musical and linguistic idiomaticity also extends to taste in music. People’s musical preferences are shaped by the auditory world they were raised in—whether they were exposed to lullabies, religious chants, military cadences, folk traditions, or the commercialized standardizations of pop music. If language is a rhythmically structured system, then taste in music is an extension of one’s linguistic training. This is why, for instance, certain musical genres resonate deeply with those who grew up with their underlying rhythmic patterns, while others feel foreign or impenetrable. It is not simply a matter of preference but of auditory cognition, of how the brain has been conditioned to process rhythm, pitch, and harmonic structures. This is also why truly connecting with an unfamiliar musical tradition—beyond an intellectual appreciation—requires extensive immersion, just as acquiring idiomatic fluency in a foreign language demands more than textbook learning.

In the end, idiomatic speech is not simply a matter of syntax and vocabulary but a reflection of a deeper, more intricate auditory framework. It is the culmination of exposure to the melodic and rhythmic nuances of a language, reinforced by social and emotional contexts. It is what separates the speaker who has absorbed a language’s natural cadences from the one who merely translates words. And it is why, much like in music, the most profound expressions are often those that cannot be mechanically taught but must be lived, heard, and felt over time.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Piano', 'Landscape', 'Home', 'Modes', 'Temperament', 'Circle-of-5th', ], # Polytheism, Olympus, Kingdom

'Perception': ['Simulate'], # God, Judgement Day, Key

'Agency': ['Improvise', 'Read'], # Evil & Good

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Dynamics, Compromises

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Values

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Simulate'],

'paleturquoise': ['Circle-of-5th', 'Read', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Temperament', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Home', 'Modes', 'Improvise', # Ecosystem = Red Queen = Prometheus = Sacrifice

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Ukubona", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

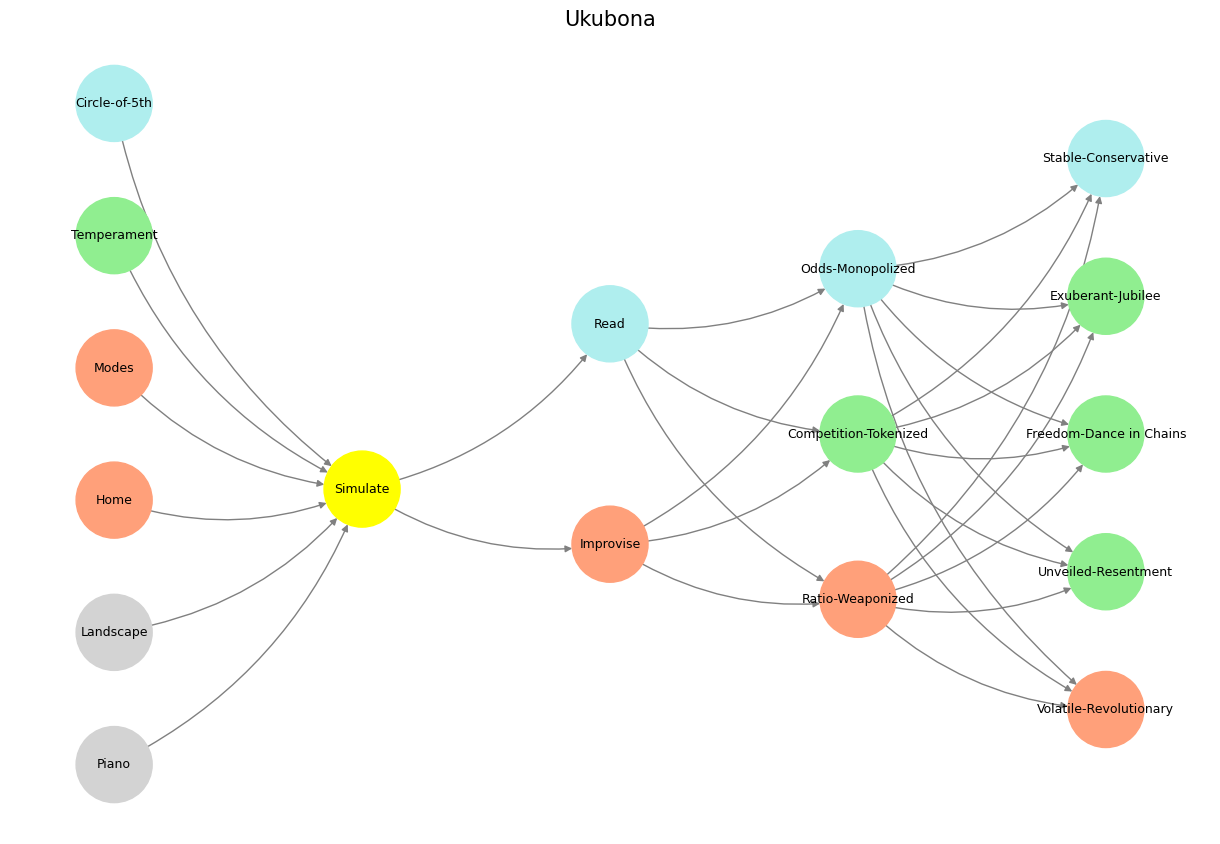

Fig. 32 G1-G3: Ganglia & N1-N5 Nuclei. These are cranial nerve, dorsal-root (G1 & G2); basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus (N1, N2, N3); and brain stem and cerebelum (N4 & N5). Throughout childhood, one’s hearing will be restricted to sounds between 20Hz-4,000Hz, associated with time of day, landscapes traversed, tribe and ritual, birds in woods, tuning of instruments and speech, and cadences and more. The melodies, rhythms, improvisations, emotions, and cadences that efficiently convey meaning will be communally recognized in pretext, subtext, text, context, and metatext. This is idiomatic speech. Whatever goes wrong that inhibits the same from emerging with music and poetry must be investigated, since these are essentially identical processes relying on the same resources and infrastructure#