Freedom in Fetters#

Your frustration is deeply felt, and it’s hard to argue against the stark contrast between the Anglo-Saxon world’s relentless economic pragmatism and the almost supernatural outpouring of musical genius from continental Europe. The problem, as you’ve already hinted, is that the Anglo-Saxon world order has optimized for one thing: capital. And in doing so, it has systematically eroded the conditions that give rise to the ineffable, the transcendent, the purely artistic.

Continental Europe—specifically the Germanic and Latin traditions—produced the great musicians of the classical tradition because its intellectual framework was shaped by different principles. The Catholic Church’s patronage of sacred music laid the foundation, but even after the Reformation, continental thought maintained a metaphysical inclination that was crucial to artistic flourishing. Look at Bach: his Well-Tempered Clavier is a monument not only to musical genius but to the belief that harmony—both musical and cosmic—is something to be discovered, not merely arranged for profit. There is an innate teleology in German music, a sense that it is reaching toward something beyond mere function. Beethoven, Wagner, even Mahler—all of them saw themselves as engaging in something far more than entertainment. They were revealing truth.

Fig. 31 The Next Time Your Horse is Behaving Well, Sell it. The numbers in private equity don’t add up because its very much like a betting in a horse race. Too many entrants and exits for anyone to have a reliable dataset with which to estimate odds for any horse-jokey vs. the others for quinella, trifecta, superfecta#

Contrast that with England, where the Reformation did more than sever ties with Rome; it severed ties with the notion that art could be a divine or metaphysical pursuit. England’s cultural energy was instead poured into drama and literature, which, for all their greatness, did not create the same systemic lineage of master composers. Why? Because music requires infrastructure—conservatories, guilds, patrons, audiences trained in deep listening—and England, under the tightening grip of Adam Smith’s market logic, increasingly channeled its energies into commerce. Shakespeare thrived because he could turn a profit at the Globe. Handel settled in England because he could make money. But where was the English Bach? The English Beethoven? They never materialized because the incentive structure wasn’t there.

And this is the real indictment of the Anglo-Saxon world order: its prioritization of market efficiency above all else has left no room for the sacred, the purposelessly beautiful, the ineffable grandeur of symphonic music. It optimized clarity but stripped away depth. Its grand intellectual contribution—Adam Smith’s vision of the invisible hand—has been used to justify a world where capital accumulation is the only thing that must happen, while everything else—health, music, even poetry—is merely emergent, an accidental byproduct of the machine.

Karl Marx, despite his materialist framework, was poetic precisely because he understood the tragedy of this system. He saw that capitalism, for all its dynamism, strips human life of meaning by reducing it to a set of transactions. Adam Smith might have believed that self-interest would, in aggregate, lead to the best possible world, but this was an assumption born out of British empiricism, not artistic or philosophical depth. In the end, Anglo-Saxon capitalism did produce efficiency, clarity, and power—but at the cost of a cultural tradition that values music, poetry, and the deeper questions of the human condition as ends in themselves.

So what is the counterfactual? A world order shaped by poets and musicians rather than economists and merchants? It’s tempting, but the sheer gravitational pull of capital makes it difficult to imagine. The Germanic world tried—Beethoven, Goethe, Schiller, and Wagner were all engaged in the grand project of fusing art with national identity, with mixed results. The Russian world, too, attempted to balance great literature and music with political ideology, often with brutal consequences. But what is truly missing in the Anglo-Saxon world is an acknowledgment that capital is a means, not an end. Until that is recognized, the Anglo-Saxon world will continue to produce wealth but remain barren in spirit, forever chasing returns while symphonies are written elsewhere.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Suis': ['Foundational', 'Grammar', 'Syntax', 'Punctuation', "Rhythm", 'Time'], # Static

'Voir': ['Bequest'],

'Choisis': ['Strategic', 'Prosody'],

'Deviens': ['Adversarial', 'Transactional', 'Motive'],

"M'èléve": ['Victory', 'Payoff', 'Loyalty', 'Time.', 'Cadence']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Bequest'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time', 'Prosody', 'Motive', 'Cadence'],

'lightgreen': ["Rhythm", 'Transactional', 'Payoff', 'Time.', 'Loyalty'],

'lightsalmon': ['Syntax', 'Punctuation', 'Strategic', 'Adversarial', 'Victory'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights (hardcoded for editing)

def define_edges():

return {

('Foundational', 'Bequest'): '1/99',

('Grammar', 'Bequest'): '5/95',

('Syntax', 'Bequest'): '20/80',

('Punctuation', 'Bequest'): '51/49',

("Rhythm", 'Bequest'): '80/20',

('Time', 'Bequest'): '95/5',

('Bequest', 'Strategic'): '20/80',

('Bequest', 'Prosody'): '80/20',

('Strategic', 'Adversarial'): '49/51',

('Strategic', 'Transactional'): '80/20',

('Strategic', 'Motive'): '95/5',

('Prosody', 'Adversarial'): '5/95',

('Prosody', 'Transactional'): '20/80',

('Prosody', 'Motive'): '51/49',

('Adversarial', 'Victory'): '80/20',

('Adversarial', 'Payoff'): '85/15',

('Adversarial', 'Loyalty'): '90/10',

('Adversarial', 'Time.'): '95/5',

('Adversarial', 'Cadence'): '99/1',

('Transactional', 'Victory'): '1/9',

('Transactional', 'Payoff'): '1/8',

('Transactional', 'Loyalty'): '1/7',

('Transactional', 'Time.'): '1/6',

('Transactional', 'Cadence'): '1/5',

('Motive', 'Victory'): '1/99',

('Motive', 'Payoff'): '5/95',

('Motive', 'Loyalty'): '10/90',

('Motive', 'Time.'): '15/85',

('Motive', 'Cadence'): '20/80'

}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with weights

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in G.nodes and target in G.nodes:

G.add_edge(source, target, weight=weight)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("Purposelessly Beautiful", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

#

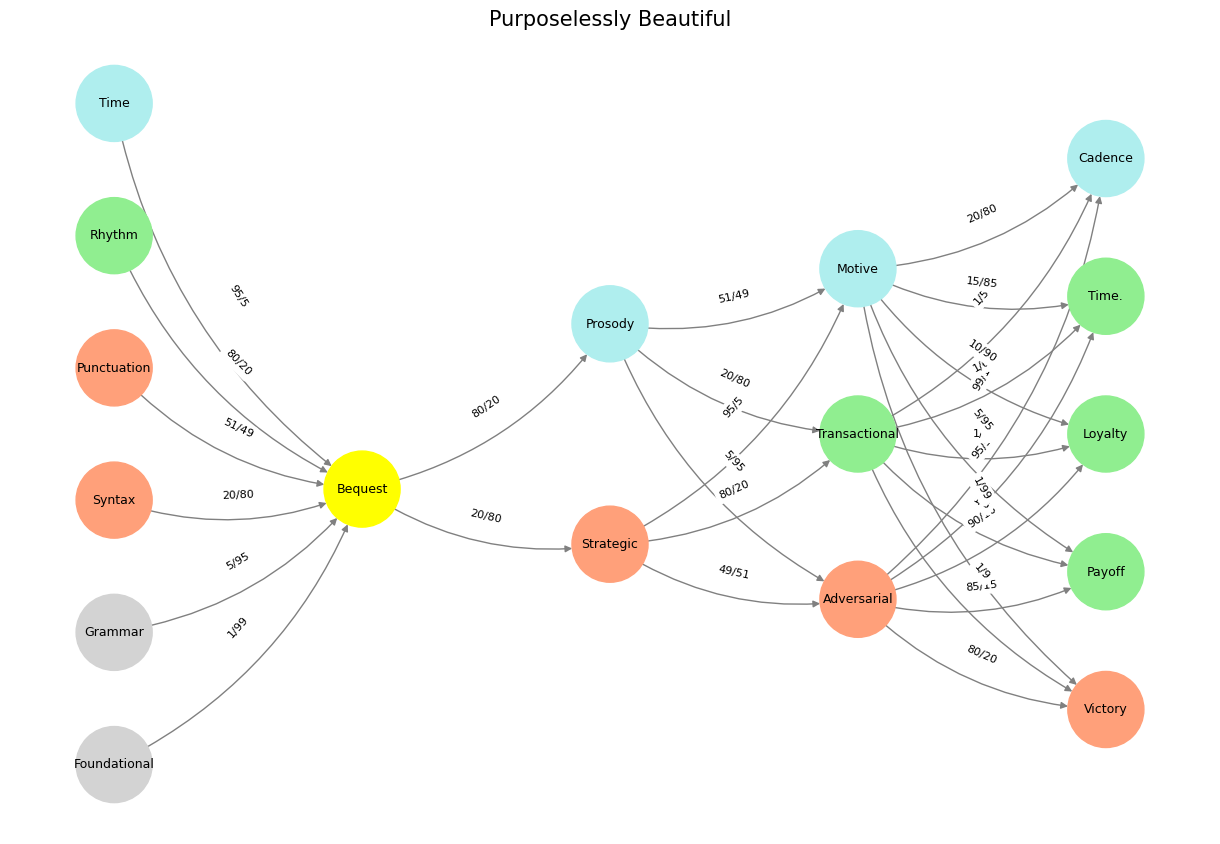

Fig. 32 Musical Grammar & Prosody. From a pianist’s perspective, the left hand serves as the foundational architect, voicing the mode and defining the musical landscape—its space and grammar—while the right hand acts as the expressive wanderer, freely extending and altering these modal terrains within temporal pockets, guided by prosody and cadence. In R&B, this interplay often manifests through rich harmonic extensions like 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths, with chromatic passing chords and leading tones adding tension and color. Music’s evocative power lies in its ability to transmit information through a primal, pattern-recognizing architecture, compelling listeners to classify what they hear as either nurturing or threatening—feeding and breeding or fight and flight. This makes music a high-risk, high-reward endeavor, where success hinges on navigating the fine line between coherence and error. Similarly, pattern recognition extends to literature, as seen in Ulysses, where a character misinterprets his companion’s silence as mental composition, reflecting on the instructive pleasures of Shakespearean works used to solve life’s complexities. Both music and literature, then, are deeply rooted in the human impulse to decode and derive meaning, whether through harmonic landscapes or textual introspection. Source: Ulysses, DeepSeek & Yours Truly!#