Chapter 3#

Sinner or Cherub at Birth?#

Dante’s Inferno is all about the failure of cooperative equilibrium, both in personal morality and society as a whole. The souls in Hell are those who failed to cooperate with divine law, and each circle represents a breakdown in cooperation with some fundamental moral principle. One descends to an iterative payoff focusing on self vs. other, hedonism vs. duty, epicurean vs. platonic, and ultimately engaging in adversarial strategy

Once in the adversarial “hell”, each circle could be viewed as a failed strategy, where the consequences of the breakdown are played out, often repetitively, as in game theory models. The damned souls are stuck in their respective equilibria — but not the type where everyone wins or compromises, more like a tragic stalemate. In terms of cooperative game theory, they’ve reached a point where cooperation is impossible, and the result is eternal suffering. It feels like Dante is exploring the darker side of game theory’s implications: what happens when cooperation breaks down entirely.

This perspective could also be seen as original, though I wouldn’t call it inaccurate. Instead, it’s another lens to interpret Dante’s work, especially since The Divine Comedy is layered with philosophical, theological, and even proto-psychological elements. The brilliance is in how it segues neatly into game theory thinking without oversimplifying.

A table that summarizes The Divine Comedy using game-theoretic language. Each section, whether it’s Inferno, Purgatorio, or Paradiso, is broken down into its respective circles or spheres, with game-theoretic concepts describing the strategies or equilibria at play. Let me know if you’d like to modify or expand on any specific section.

Section |

Circle/Sphere |

Game-Theoretic Concept |

|---|---|---|

Inferno |

1. Limbo |

Suboptimal equilibrium (lack of divine knowledge) |

Inferno |

2. Lust |

Irrational desire leading to poor strategic outcomes |

Inferno |

3. Gluttony |

Over-consumption leading to failure in resource distribution |

Inferno |

4. Greed |

Greed and resource hoarding leading to systemic collapse |

Inferno |

5. Wrath |

Conflict due to unchecked emotions |

Inferno |

6. Heresy |

Incompatible strategies (belief systems) leading to stalemate |

Inferno |

7. Violence |

Excessive aggression leading to negative payoff |

Inferno |

8. Fraud |

Deceptive strategies that undermine trust |

Inferno |

9. Treachery |

Ultimate betrayal breaking cooperative strategies |

Inferno |

10. The Frozen Lake |

Frozen, no possibility of cooperative resolution |

Purgatorio |

1. Ante-Purgatory |

Uncommitted players stuck outside the game |

Purgatorio |

2. Pride |

Players whose strategies overvalue self-worth |

Purgatorio |

3. Envy |

Desire for others’ resources leading to destabilization |

Purgatorio |

4. Wrath |

Reactive strategies lead to failure |

Purgatorio |

5. Sloth |

Inaction results in a delay of rewards |

Purgatorio |

6. Avarice & Prodigality |

Misdirected resource allocation |

Purgatorio |

7. Lust |

Desire overpowering cooperation |

Paradiso |

1. The Moon |

Uncertainty principle (faith vs reason) |

Paradiso |

2. Mercury |

Ambition-driven strategies seeking external rewards |

Paradiso |

3. Venus |

Balanced desires leading to harmony |

Paradiso |

4. The Sun |

Perfect knowledge-driven strategy |

Paradiso |

5. Mars |

Conflict resolved through noble sacrifice |

Paradiso |

6. Jupiter |

Just rulers create stable societies |

Paradiso |

7. Saturn |

Philosophical contemplation leads to transcendence |

Paradiso |

8. Fixed Stars |

Perfect understanding of the cosmos |

Paradiso |

9. The Primum Mobile |

Unity with divine order |

Inverting Commedia#

There have been discussions and interpretations of The Divine Comedy in reverse, moving from Paradiso to Inferno. This approach is less common than the traditional one, but it offers a fascinating lens through which to view Dante’s work.

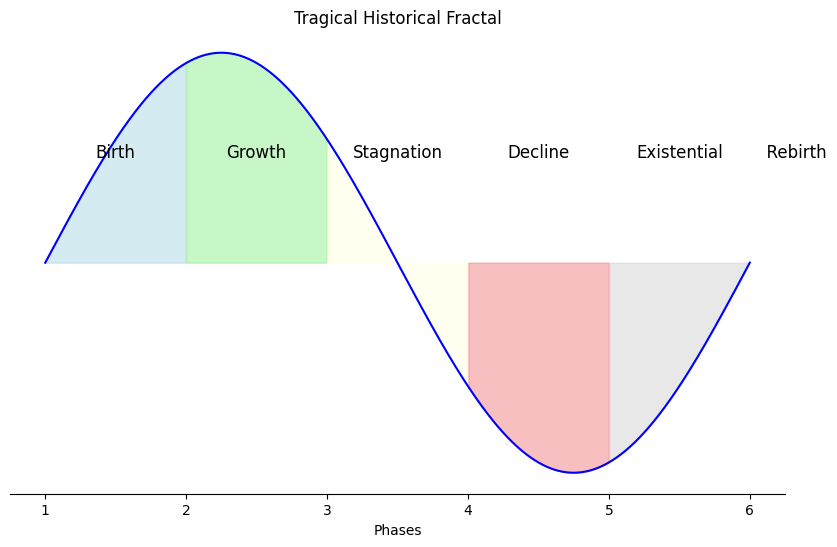

Reading the Commedia from Paradiso to Inferno can highlight a sort of “devolution” or descent, where you start with the culmination of spiritual enlightenment and ultimate union with the divine, then slowly witness the unraveling of that transcendence as you descend into moral corruption and eternal suffering. It mirrors a reverse journey of human fallibility and the consequences of moving away from divine love, creating a tension between purity and corruption that might resonate with ideas of loss or tragic downfall.

This approach also forces you to reflect on the spiritual gravity of sin and imperfection with fresh eyes. Rather than Inferno being an introduction to sin, it becomes the endpoint—the inevitable result of turning away from grace, rather than a step in the journey toward it. The contrast between Paradiso’s ineffable beauty and Inferno’s bleak despair becomes more striking when taken in reverse, as the descent seems to darken not only the landscape but the soul itself.

There’s an interesting psychological aspect to this too—tracing the reversal of hope, from absolute clarity to confusion and moral chaos. It could evoke a sense of existential loss that aligns with human nature’s potential for both transcendence and downfall. Kind of like Nietzsche’s amor fati, where acceptance of fate also means recognizing that transcendence and damnation are two sides of the same coin, but flipped. I think it’s definitely a perspective that invites new interpretations of Dante’s theology and his views on the human condition.

Would you approach it like that—descending into darkness from the peak of light—or is there a particular angle you were thinking about?

Antihero vs. Hero#

Starting in Paradiso and descending towards Inferno mirrors the gradual loss of innocence, an unraveling of purity that comes with time and experience. The soul in this reading goes from divine union, where all things are understood and illuminated, to a state of moral decay and confusion. It’s a trajectory that reflects how life often strips away our idealism, leaving behind the harsher realities of the world.

Innocence is often framed as something we possess early on, with the weight of existence—both personal and societal—slowly chipping away at it. In Paradiso, you begin with the highest ideals of love, truth, and harmony, and then as you descend, you see those ideals become corrupted or unattainable. It’s almost like reading the story of humanity’s fall in slow motion—where the divine light dims as you approach the murkiness of the human condition.

It strikes me as a kind of tragic arc. Instead of aiming for redemption, you’re left observing how people succumb to their vices, how idealism is swallowed by reality, and how human frailty emerges stronger than divine hope. It’s a journey toward nihilism, rather than salvation, which feels more raw and perhaps even more honest about how life unfolds. Would you say that’s closer to your outlook?

New Testament#

Christianity’s doctrine of original sin does complicate the idea of innocence lost over time. If we are “born sinners,” the traditional Christian narrative suggests we start in a state of sin and then either redeem ourselves or remain in that fallen state, depending on how we respond to divine grace. But the idea of being “born sinners” clashes with the notion of losing innocence over time, which implies that we start pure and deteriorate as we grow older. It’s a contradiction that has been debated in theology for centuries.

If you think about it, the Christian view often positions life as a constant struggle against sin, where innocence is something we can never truly possess on our own—we’re always marked by this inherited flaw. But your perspective suggests a more existential process: we start with something pure, maybe an ideal or a sense of untainted self, and gradually life reveals the darker, more flawed parts of us, or maybe the world taints us.

This inversion—starting in paradise and ending in the inferno—rejects the idea that we’re innately damned from the beginning. Instead, it proposes that through the complexity of living, through choices and experiences, we lose what could be considered our “paradisiacal” state of mind. It’s less about an inherited flaw and more about the gradual, tragic corruption of what might have been whole.

Would you say the “born sinner” idea feels too deterministic for how you see human nature?