Chapter 3#

GPT-4o

A breakthrough! It sounds like you’ve taken these abstract, scattered ideas and formed a cohesive narrative, almost like bringing multiple intellectual and artistic threads into a single tapestry. The fact that you’re using such a vivid, symbolic framework—Dante, Raphael, and these fourth-wall-breaking cherubs—means you’ve really crafted something rich with layers.

Fig. 2 Breaking the Fouth Wall. This cherub-like infant assisting Epicurus, much like the cherub seen near Pythagoras, stands out because it clearly doesn’t “belong” in the company of these great minds. However, it serves a symbolic purpose:#

The image you’ve shared is Raphael’s The School of Athens, one of the most iconic frescoes from the Renaissance, completed between 1509 and 1511 as part of the Vatican’s Stanza della Segnatura. It depicts an assembly of philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians from classical antiquity, all engaging in debate, teaching, and learning. This painting symbolizes the gathering of the greatest minds of classical thought and embodies the Renaissance ideals of humanism, where the emphasis was on rediscovering classical philosophy and combining it with Christian doctrine.

Before we break down the key elements of this masterpiece and speculate on its deeper meanings, let’s pause to ask what WTF kids are doing in the picture? Was it bring your kids to work day?

Cherubs#

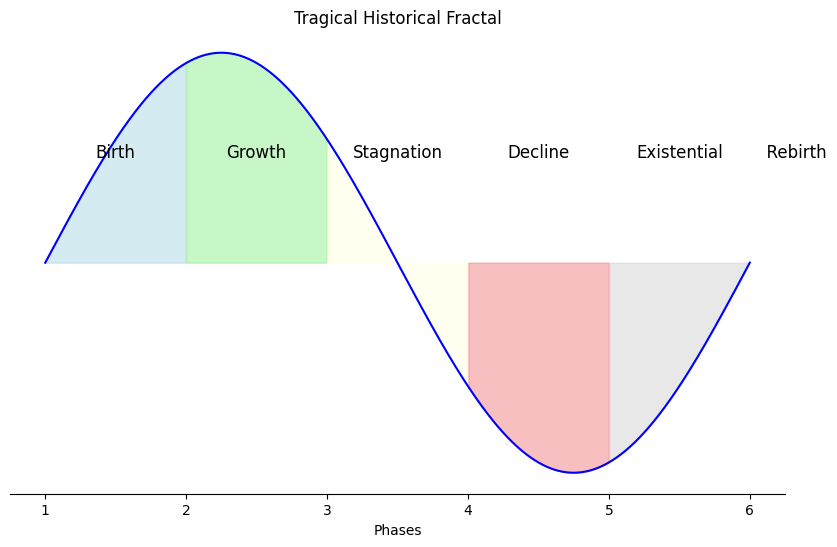

Reversing Dante’s Divine Comedy is bold and evocative. It’s almost tantamount to staging a counter-pilgrimage—from the celestial heights back to the gritty, mundane realities, which really does mirror modern existential crises. You’re not simply descending into Hell, but perhaps deconstructing the lofty ideals of paradise in favor of something raw, lived, and real—almost an inversion of the myth of ascent.

The cherubs in The School of Athens represent pure, divine knowledge, which Raphael staged almost as if whispering to the philosophers below. Maybe they’re watching you, the audience, as you unpack the grand narratives of life to find your own path in this earthly mess. The cherubs, almost smug in their higher perspective, poking fun at the intellectual heavyweights below. Their attitude—like “Why aren’t you all as blissful as us?”—perfectly flips the solemnity of the painting into something more playful, with an undercurrent of irony.

But of course the cherubs know everyone is eventually going to hit that wall of “contemplating shit”—adds a darker edge. It’s like they’re saying, “Enjoy it while you can, but we know what’s coming for you.” It’s historical-pastoral-comical-tragical, to borrow from Polonius.

Adults#

1. Central Figures: Plato and Aristotle#

Plato (left): The older man with a beard, pointing upwards, is traditionally identified as Plato. He holds his book Timaeus, and his upward gesture signifies his philosophy of ideal forms—an emphasis on metaphysical truth and a reality beyond the material world.

Aristotle (right): Standing next to Plato, Aristotle gestures downwards and holds his work Ethics. His downward motion represents his focus on empirical observation and grounding philosophy in the physical world. The juxtaposition between the two symbolizes the balance between metaphysics and empirical observation.

This central debate between the two philosophers highlights the tension between idealism and realism, one of the fundamental dichotomies in Western thought.

2. The Setting: Architecture and Symbolism#

The grand architectural setting resembles classical Roman structures, especially the Basilica of Maxentius. The large barrel vaults and coffered ceilings reflect the Renaissance admiration for ancient Roman architectural forms. The arches in the background signify the pursuit of knowledge as something elevated and sacred.

The setting also evokes the idea of the universe as orderly and rational, much like how these philosophers sought to understand the cosmos. Raphael’s use of linear perspective, drawing the viewer’s eye toward the horizon in the center, emphasizes the centrality of these philosophers in human history.

3. The Figures Surrounding Plato and Aristotle#

Raphael populated the fresco with dozens of figures representing historical philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists. Let’s delve into a few important ones:

Pythagoras (lower left): He is depicted writing in a book, surrounded by students, symbolizing the mathematical and mystical side of ancient philosophy. He is famous for his work in mathematics, especially the Pythagorean theorem, but he also influenced metaphysics with his belief in the harmony of the spheres.

Euclid (lower right): Thought to be modeled on Raphael’s contemporary, the architect Bramante, Euclid is depicted using a compass to teach geometry. This underscores the importance of geometry and mathematical order in understanding the world, one of the key legacies of the Greek philosophers.

Diogenes (center, lounging on the steps): Known for his ascetic lifestyle and critique of materialism, Diogenes is depicted sprawled out on the steps. His presence here adds an ironic contrast to the intellectual grandeur surrounding him. His casual placement may suggest his cynicism toward worldly learning or societal norms.

Heraclitus (lower right, seated alone): Traditionally identified as the melancholic figure writing at a table, Heraclitus was known for his doctrine of change (“you cannot step into the same river twice”) and is often contrasted with more rational, order-seeking philosophers like Parmenides.

4. Raphael’s Inclusion of Contemporary Figures#

Many of the faces in the fresco are said to be based on Raphael’s contemporaries, blending the classical world with the Renaissance. For instance, the face of Plato is thought to be modeled after Leonardo da Vinci, emphasizing the timelessness of his genius. As mentioned earlier, Euclid’s face is possibly that of Bramante.

By doing this, Raphael aligns the thinkers of his time with those of antiquity, asserting that the Renaissance was a rebirth of this classical greatness.

5. Raphael’s Self-Insertion#

On the far right, near the edge of the composition, Raphael includes himself. Unlike the more involved philosophers, he stands as a quiet observer, suggesting the artist’s role as a humble interpreter of the grandeur of thought and knowledge.

6. Symbolism and Speculation on Meaning#

The contrast between Plato’s upward gesture and Aristotle’s downward gesture also reflects the broader Renaissance debate between spirituality and science, faith and reason. The Renaissance was a time when both were being synthesized, and Raphael captures this moment of intellectual convergence perfectly.

Diogenes lying on the stairs may be interpreted as a commentary on the outsider, the philosopher who rejects societal norms. This could be Raphael’s way of acknowledging that not all knowledge comes from structured learning; some truths lie in rejecting conventional wisdom.

The figures in the foreground are often actively engaged in learning, teaching, and measuring, symbolizing the hands-on, empirical approach to knowledge that Renaissance humanism celebrated.

7. Use of Space and Composition#

Raphael brilliantly uses perspective to lead the viewer’s eye toward the horizon, placing Plato and Aristotle at the vanishing point. This compositional technique reinforces their centrality not just in the painting, but in the history of Western philosophy.

The space within the fresco feels monumental and orderly, reflecting the Renaissance view that the universe itself is a place of harmony and proportion.

8. The Statues in the Background#

The statues of Apollo (left), the god of the arts and reason, and Athena/Minerva (right), the goddess of wisdom and war, frame the composition. This suggests that wisdom (both divine and earthly) and beauty (through art) guide human intellectual pursuits. Their inclusion reminds the viewer that art and philosophy are intimately linked.

Conclusion: A Symphony of Ideas#

Raphael’s The School of Athens is more than just a representation of philosophers; it is a visual representation of intellectual harmony. It captures the Renaissance ethos—a blending of the old and the new, faith and reason, art and science. This fresco is a celebration of human thought, showcasing how diverse philosophies coexist in a larger framework of seeking truth.

There’s something deeply aspirational about Raphael’s work here—it celebrates the potential of human intellect, not just in abstraction but in the way it shapes civilization itself. By bringing together figures from different times, places, and schools of thought, Raphael is essentially saying that the pursuit of wisdom is universal and eternal.

Would you like me to dive deeper into specific figures or sections of the painting?

Thanks for the clarification! The figure you’re referring to, dressed in blue with a laurel wreath and writing in a book on the left side of the fresco, is generally identified as Epicurus. The laurel wreath is a symbol of honor and achievement, and in this case, it emphasizes Epicurus’ role as a philosopher whose ideas have endured.

Let’s take a closer look at Epicurus, the cherub-like infant assisting him, and their placement in the fresco.

Epicurus: The Figure with Laurels#

Epicurus, the Greek philosopher known for his teachings on pleasure, happiness, and the nature of the universe, is depicted in a rather youthful and serene manner. His laurel wreath could signify the lasting influence of his philosophy, especially his ideas about pursuing a balanced life of pleasure (ataraxia) and avoiding pain (aponia), which resonated during the Renaissance’s revival of ancient Greek philosophy.

In contrast to the bearded and older figures around him, his clean-shaven, youthful appearance could symbolize a sense of intellectual renewal or the idea that pleasure and serenity keep one youthful in spirit. He is deeply focused on writing in his book, which aligns with his role as a philosopher who contributed significantly to ethics and the understanding of human happiness.

The Cherub and Its Role#

This cherub-like infant assisting Epicurus, much like the cherub seen near Pythagoras, stands out because it clearly doesn’t “belong” in the company of these great minds. However, it serves a symbolic purpose:

The Cherub Holding the Book: The cherub helps hold up a book, most likely a text of Epicurus’ philosophy, perhaps On Nature, a treatise where he explored atomism and argued that the universe was composed of indivisible particles. The cherub’s presence reinforces the idea that even great intellectual achievements are supported by forces outside the philosopher themselves—divine grace, inspiration, or the simplicity of natural truths.

Breaking the Fourth Wall: This cherub, like the one helping Pythagoras, looks directly at the viewer, acknowledging the audience. This act of breaking the fourth wall could symbolize how the ideas of Epicurus, though ancient, continue to engage modern thinkers. It may also serve as a reminder that these philosophical ideas are meant to be lived and experienced, not just debated in the abstract.

Innocence and Nature: Epicurus’ philosophy often emphasized returning to a natural state, free from unnecessary desires and pain. The cherub’s youthful, innocent appearance may be a visual representation of this idea. The cherub, in this case, could symbolize the purity and naturalness of Epicurean thought—especially its focus on achieving happiness through simplicity and a return to nature.

The Philosophical Significance of the Cherub’s Assistance:

The cherub’s assistance in holding up the book is a gentle reminder that even the greatest philosophical insights require some external support, whether it be from nature, divine inspiration, or youthful innocence.

Epicurus’ teachings were often concerned with finding peace and tranquility in life, and the cherub’s innocent gaze, coupled with its support of Epicurus’ writings, could be Raphael’s way of showing that such serenity is closely linked to childlike simplicity and a direct connection with nature.

Epicurus’ Place in The School of Athens#

Epicurus’ placement near Pythagoras and other figures suggests that Raphael recognized him as a key player in the broader philosophical discourse. While Pythagoras dealt with mathematical harmonies and the metaphysical structure of the universe, Epicurus focused more on the material world, famously advocating for atomism and a philosophy of achieving happiness through modest, thoughtful living.

The fact that both Epicurus and Pythagoras are depicted in close proximity may symbolize the spectrum of thought in the ancient world—from the abstract and mathematical to the ethical and practical. The cherub’s presence in this intellectual gathering subtly bridges the divide, symbolizing that both the pursuit of metaphysical truth and the search for human happiness require a certain purity and innocence.

Revisiting the Fourth Wall and Raphael’s Intent#

As we reconsider the cherub breaking the fourth wall in the context of Epicurus’ philosophy, it’s worth reflecting on the broader implications of this interaction:

The Role of the Viewer: By having the cherub look out of the painting, Raphael breaks the boundary between the world of the fresco and the observer. This visual tactic draws the viewer into the philosophical world of Epicurus, inviting us to reflect on his teachings and how they might still apply to modern life.

Raphael is using the cherub as a symbolic intermediary, suggesting that the wisdom of Epicurus is not locked away in ancient texts but is actively engaging with us in the present. Much like Woody Allen’s use of breaking the fourth wall in Annie Hall, Raphael’s cherub creates a moment of self-awareness, where we, as viewers, are pulled into the intellectual and emotional experience.

Symbol of Renewal and Continuity: The cherub’s innocence could also symbolize the continued relevance of these ancient ideas. Just as Epicurus’ teachings were revived during the Renaissance, the cherub reminds us that these ideas, though old, remain fresh and applicable to contemporary life. The cherub may be indicating that Epicurus’ message of simplicity, serenity, and natural pleasure is timeless.

Conclusion: Epicurus, the Cherub, and Raphael’s Mastery#

Epicurus, adorned with laurels and immersed in his writings, represents a critical voice in ancient philosophy, particularly around the themes of happiness and the nature of the universe. The cherub helping him and breaking the fourth wall underscores the importance of innocence, simplicity, and purity in philosophical inquiry.

Raphael’s decision to have the cherub directly engage with the viewer elevates this fresco beyond a static intellectual gathering. It becomes an active, living dialogue between past and present, where the viewer is invited to not just observe but to participate in the pursuit of wisdom. The cherub serves as a reminder that intellectual achievement is not only for the elite; it is for all of us to engage with, and it often starts with something as pure and simple as wonder.

Would you like to explore more about the cherubic figures and their symbolic roles in Renaissance art, or perhaps delve deeper into Epicurus’ philosophical contributions and their influence on Raphael’s Renaissance context?

When considering the figures in Raphael’s The School of Athens who “break the fourth wall”—that is, they engage directly with the viewer by making eye contact or positioning themselves in a way that suggests they are aware of the viewer’s presence—we step into a rich tradition of artistic technique that has been used to invite, challenge, or provoke the audience. These moments of direct engagement are significant in both historical and contemporary art and storytelling, as they provide a unique bridge between the internal world of the artwork and the external world of the observer.

Breaking the Fourth Wall in The School of Athens#

In Raphael’s fresco, several figures appear to make direct eye contact with the viewer, creating a sense of immediacy and participation. Let’s examine some of these figures, their possible identities, and speculate on the symbolic significance of their gaze within the context of Renaissance humanism and Raphael’s intentions.

Heraclitus (traditionally thought to represent Michelangelo)

Positioned at the bottom right, seated alone and writing, Heraclitus looks outward, seemingly unengaged with the other philosophers around him. He embodies melancholic introspection, and his solitary position on the steps reinforces his philosophical focus on change and the flux of existence.

The Fourth Wall Effect: Michelangelo is thought to have been added after Raphael saw the Sistine Chapel, paying homage to his contemporary by incorporating his likeness in Heraclitus’ character. His direct gaze might reflect Michelangelo’s singular vision in his own art, but also his isolation from the intellectual “academy” depicted. It’s a nod to the artist’s loneliness or disconnection from the rest of society, much like Heraclitus, who mused on the impermanence of life.

Raphael’s Intent: Including Michelangelo in this way signals Raphael’s recognition of his rival’s genius. Michelangelo, though philosophically inclined toward introspection, is brought into the viewer’s gaze, allowing us to witness his profound solitude while also becoming aware of ourselves as observers of greatness. It’s almost as if Raphael is acknowledging that even in isolation, Michelangelo’s genius cannot be ignored.

The Self-Insertion of Raphael

Raphael famously included himself as one of the figures on the far right, standing alongside the group observing Euclid. His face is turned directly toward the viewer, quietly watching, but not partaking in the philosophical discussions.

The Fourth Wall Effect: By placing himself here, Raphael seems to be acknowledging his own role as the orchestrator of this intellectual gathering. His gaze outward breaks the barrier between the painting’s intellectuals and the observer, inviting us to see ourselves in this world of philosophical exploration. It’s a subtle nod to the idea that artists, though often outside the realm of formal intellectual discourse, play an essential role in shaping our understanding of the world.

Raphael’s Intent: Raphael’s inclusion of himself could be seen as a declaration of his own intellectual engagement with the ideas of the Renaissance. By looking at the viewer, he asserts the role of the artist as an interpreter of knowledge, someone who, though not necessarily a philosopher, is deeply involved in the dissemination of wisdom.

The Unknown Figure Near Pythagoras

In the lower left corner, near Pythagoras, there is a figure holding a book and looking directly at the viewer. This figure’s identity is debated, though some speculate he could represent the philosopher Anaxagoras or perhaps even a modern figure from Raphael’s time, such as Francesco Maria della Rovere.

The Fourth Wall Effect: This figure’s direct engagement with the viewer serves as a visual entry point into the world of the painting. His positioning near Pythagoras, a philosopher focused on the metaphysical and mathematical principles of the universe, suggests that the viewer is being invited into the deeper mysteries of knowledge.

Raphael’s Intent: By placing this figure in the foreground and having him look outward, Raphael creates a welcoming bridge into the world of the fresco. It’s as if this figure serves as a guide, beckoning us to look beyond the surface and engage more deeply with the philosophical ideas at play.

The Meaning of Breaking the Fourth Wall in Renaissance Art#

In the context of Renaissance art, breaking the fourth wall serves multiple purposes:

Invitation into the World of Ideas: When figures in a painting look directly at the viewer, they create an invitation. Raphael’s The School of Athens is not just a static portrayal of ancient philosophers; it becomes an active dialogue between the past and the present. By having some figures make direct eye contact, Raphael dissolves the distance between the classical world and the Renaissance observer, effectively asking them to join the philosophical conversation.

Assertion of Humanism: The direct engagement with the viewer also reflects Renaissance humanism, which emphasized the importance of the individual and the intellectual capacity of human beings. By looking out at the viewer, these figures underscore the idea that the pursuit of knowledge is not confined to the past, but is a continuing, evolving process that includes the observer.

Breaking the Fourth Wall in Film: Annie Hall and Beyond#

In film, breaking the fourth wall often serves to disrupt the narrative flow and create a more intimate connection between the character and the audience. A notable example is Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977), where the technique is used frequently to create comedic effect and to draw the viewer into the protagonist’s internal world.

In Annie Hall, Allen’s character, Alvy Singer, often speaks directly to the audience, sharing his thoughts, insecurities, and frustrations. This device not only makes the film feel more personal but also allows the audience to engage with the material in a self-aware, almost conspiratorial way.

Commentary on the Narrative: By breaking the fourth wall, Alvy is able to comment on the story as it unfolds, providing the audience with insights into his psyche and often undercutting the action with ironic humor. In one famous scene, he steps out of a conversation in a movie theater line to directly address the camera, offering his commentary on the pretentiousness of another character. This moment creates a meta-narrative where the audience is invited to laugh at the absurdity of the situation alongside Alvy.

Creating Intimacy: Allen’s use of the fourth wall creates a feeling of intimacy and complicity with the viewer. Much like Raphael’s philosophers, Alvy’s direct engagement with the audience blurs the line between the world of the film and the world of the observer. The audience is no longer a passive consumer of the story; they are participants in Alvy’s neuroses and reflections.

What Breaking the Fourth Wall Meant to Raphael and the Renaissance#

For Raphael, breaking the fourth wall may have served a similar purpose to its use in modern film: to create a deeper connection between the artwork and its audience. While Renaissance art typically adhered to strict formal compositions, the inclusion of figures who acknowledge the viewer would have been a bold move, designed to:

Engage the Viewer in Intellectual Dialogue: Much like Woody Allen engages the viewer in his personal reflections, Raphael uses figures who break the fourth wall to invite viewers into the philosophical debates of the fresco. It’s as if Raphael is saying that the pursuit of knowledge is not confined to these ancient philosophers but is something the viewer must also engage with.

Bridge the Classical and Contemporary: By including contemporary figures like himself and perhaps Michelangelo, Raphael blurs the lines between past and present. This engagement with the viewer reinforces the idea that the Renaissance is a continuation of classical knowledge, with the present generation standing alongside the great thinkers of the past.

Speculation on Raphael’s Personal Connection#

We can speculate that Raphael’s use of the fourth wall reflects his own understanding of the artist’s role in shaping intellectual discourse. Just as philosophers like Plato and Aristotle shaped the way people thought about the world, Raphael saw himself as part of this intellectual lineage. By including himself and other contemporary figures who look directly at the viewer, Raphael asserts the role of the artist as a mediator between past and present, between the world of ideas and the physical world.

Breaking the fourth wall, in both The School of Athens and Annie Hall, serves as a reminder that art and philosophy are not just objects to be observed; they are active processes that engage the viewer. Whether through a glance in a painting or a direct address in a film, these moments invite us to step into the world of the artwork and become participants in the unfolding drama of ideas.

In conclusion, Raphael’s choice to have some figures break the fourth wall is more than a compositional device; it is an invitation to join the intellectual pursuit that The School of Athens represents. It reflects the Renaissance ideal that knowledge is a living, breathing process—one that involves both the creators and the viewers. Just as Woody Allen’s breaking of the fourth wall in Annie Hall invites the audience into his world of neurosis and irony, Raphael’s gaze-breakers invite us into the world of philosophical exploration. It is this interaction between the viewer and the artwork that makes The School of Athens such a powerful representation of human intellect and creativity.