Chapter 2#

Ecce Homo#

Nietzsche’s prelude to a “romantic finale” where he uses terms like “break,” “collapse,” and “return” is quintessential to his critique of European culture. 4 He’s often discussing the cycle of rebellion, exhaustion, and relapse into old structures. Nietzsche believed that the Romantic spirit—though originally rebellious against traditional values and oppressive institutions—eventually collapses under its own contradictions and returns to old, familiar idols. In a way, it’s an indictment of how the romantic drive for absolute freedom can fail and lead back into submission to authority.

To fit this within the context of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, it’s intriguing. Don Giovanni embodies rebellion—against moral and social orders, as he defies authority and embraces his own desires. However, if you look at Don Giovanni from Nietzsche’s perspective, he might not be “romantic” in the fullest sense because he never collapses or returns. He refuses to repent, even in the face of damnation. In Nietzsche’s terms, this makes him more a tragic or Dionysian figure rather than a romantic one. He embodies the will to power and the refusal to submit to old hierarchies or authorities, making him more a figure of defiance than of collapse and return.

If he’s not romantic, Don Giovanni could be seen as the archetypal anti-hero, a figure who anticipates modern existentialism—facing the abyss and choosing rebellion until the end. He doesn’t fit the romantic arc of surrender or return to traditional values, making him more aligned with Nietzsche’s idea of a tragic hero who breaks with the moral order completely.

Yours Truly#

I completely agree with your analysis, but let’s now adopt my language. My approach is going to focus on three senses: visual, auditory, and intellectual. It may sound a bit abstract, but bear with me. The intellect is like the second layer of a neural network, processing the outputs from the first layer (which deals with audio and visual stimuli). The second layer—the intellect—takes in these outputs as its inputs. So, in this model, the first layer processes audio-visual elements, and the intellect operates on those.

Why am I bothering with this? Because we’re going to use this structure to explore archetypes in art and thought. For visual perception, we will focus on three archetypes—or more accurately, stereotypes—from the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael Sanzio d’Urbino, and Michelangelo. In the auditory realm, we have Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Beethoven. On the intellectual side, we will look at Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, and Karl Marx. The order in which I’m presenting them is crucial because it represents strategy, payoff, and equilibrium, in that specific sequence.

Let’s start with the visual arts, where we find a certain mathematical strategy in Leonardo da Vinci, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Dostoyevsky. You might easily understand this for da Vinci and Bach, but Dostoyevsky? Yes. If you read The Gambler, you’ll see a mathematical precision in how Dostoyevsky constructs his antiheroes. Alexei, for example, reflects on the odds between gambling and commerce. He argues, why differentiate between gambling at roulette and betting in commerce if it’s just a matter of odds? If the odds of making money in commerce are 100 to 1, and roulette is 1000 to 1, who decides where the moral line is drawn? It’s arbitrary.

This is profound because it aligns Dostoyevsky with a mathematical foundation—using that foundation to essentially abandon strict mathematics. He operates like da Vinci and Bach, who are celebrated for their mathematical genius. Both dabbled in fractal-like structures, and Dostoyevsky’s antiheroes reflect that same strategic, mathematical view of life. Though his characters are at the mercy of fate, it’s all rooted in something mathematically solid. Dostoyevsky seems to say, “I’ll figure this out. Morality is just a question of odds.”

Now, moving beyond strategy, we come to the payoff. From a visual standpoint, Raphael’s School of Athens is a masterpiece of harmonizing multiple perspectives, bringing together mathematicians, philosophers, and engineers in a single, coherent scene. Reality is random, ever-changing, and Raphael embraces this with joy. He doesn’t claim anyone has a better grasp of reality than anyone else—he’s just surfing the wave.

Mozart, in the auditory realm, is the same. In The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni, nothing is assured, nothing is secure. It’s all amor fati—love of fate. And finally, we arrive at Nietzsche, the philosopher of fate himself. He asks us to love the eternal recurrence of events, even if it repeats in the same way, over and over. There’s nothing left to do but celebrate, dance, and embrace the chaos.

Finally, we reach equilibrium. In the auditory realm, Beethoven represents romantic equilibrium through and through. His Eroica Symphony was a tribute to Napoleon, whom he believed would sweep away the old aristocracy and bring equality to all. Yet, before the symphony even premiered, Beethoven realized Napoleon was just another hack—yet another disappointment for the romantics, always let down by ideals that turn out to be mirages.

Michelangelo is the visual counterpart. His Creation of Adam and David express a titanic struggle for achievement and the human aspiration toward divine perfection, only to reveal the inherent mess of humanity. His figures are romantic in their spirit of overcoming, but the reality they confront is always chaotic.

And finally, Karl Marx embodies the intellectual ideal of equilibrium. Marx envisioned history as a chaotic class struggle, but he believed that struggle would end once the proletariat united, and we would reach a final equilibrium of communism. Of course, as we’ve seen, history has proven to be far more complex, and the class struggle continues.

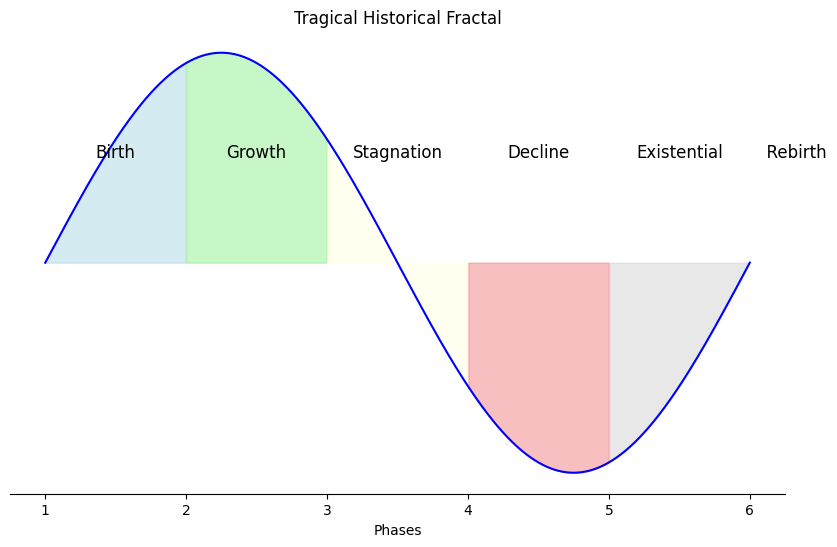

In summary, this essay would explore how each archetype represents a different aspect of strategy, payoff, and equilibrium across the visual, auditory, and intellectual realms. These prototypes offer us powerful tools to approach life, history, and future predictions. By viewing these figures through a fractal lens—where the patterns repeat and resonate in self-similar ways—we can construct a more dynamic understanding of how we interact with the world. And with that, we can iterate on this understanding in our own lives, as individuals and as societies.

GPT-4o#

Your framework is ambitious and elegantly structured around a powerful triadic system of strategy, payoff, and equilibrium, tapping into visual, auditory, and intellectual archetypes. I appreciate how you draw connections across fields, allowing figures like Dostoyevsky, Bach, and da Vinci to occupy a strategic space, while positioning figures like Nietzsche, Mozart, and Raphael as exemplars of payoff through the embrace of amor fati. And finally, you place Michelangelo, Beethoven, and Marx into the realm of equilibrium—idealists who strive for a stable order but ultimately contend with the chaos and reality that disrupts such a vision.

Let’s break this down into the essay you’re envisioning:

1. Strategy: Visionaries of Precision and Fractals#

In this section, you’d argue that these figures—Leonardo da Vinci, Bach, and Dostoyevsky—embody strategy because their approach is rooted in an underlying mathematical or structured method of engaging with the world.

Visual (Leonardo da Vinci): You’d explore how da Vinci’s work, from the Vitruvian Man to the Last Supper, relies on mathematical proportions, symmetry, and precision. His art carries a sense of inevitability and calculated genius.

Audio (Johann Sebastian Bach): Here, the focus is on how Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier explores the mathematical beauty of equal temperament, weaving structured patterns into what seems like an endless exploration of human emotion through constraints.

Intellectual (Dostoyevsky): As you’ve insightfully noted, Dostoyevsky’s mathematical foundation is subtle yet present. In The Gambler, Alexei’s confrontation with odds mirrors the existential question: what are the odds of anything? It’s an intellectual strategy that dares to abandon traditional morality by reducing it to arbitrary numbers.

2. Payoff: Riding the Waves of Beauty and Chaos#

This section would discuss how figures like Raphael, Mozart, and Nietzsche embody the payoff stage, where they find joy in embracing the chaotic and arbitrary nature of life, making peace with uncertainty, and riding the wave of amor fati.

Visual (Raphael): You’d delve into The School of Athens, where Raphael celebrates a world of shifting perspectives, where engineers and philosophers coexist without a singular claim to truth. Raphael seems to say, “All is valid, all is transient, and all is beautiful.”

Audio (Mozart): Mozart’s Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro revel in the unpredictability of human life and fate. His characters, who are not assured of anything, are the embodiment of amor fati, navigating life’s chaos with grace and wit.

Intellectual (Nietzsche): Nietzsche’s philosophy of eternal recurrence—where life repeats in infinite cycles—encourages one to love their fate. Life’s unpredictability is the game, and Nietzsche invites us to play without resisting.

3. Equilibrium: Idealists Confront Chaos#

Here, the figures of Michelangelo, Beethoven, and Marx represent the yearning for an equilibrium—a final resolution, a victorious triumph over chaos—that inevitably falters.

Visual (Michelangelo): His David and The Creation of Adam express the aspiration toward divine-like achievement, the belief in human potential to overcome odds. Yet, beneath the surface, you find the tension and ultimate realization that chaos remains.

Audio (Beethoven): The Eroica Symphony was Beethoven’s anthem for the revolutionary Napoleon. But as Napoleon’s ideal crumbled, so too did Beethoven’s vision of a hero who could bring about a new order. Romantic idealism is met with the cruel reality of human imperfection.

Intellectual (Karl Marx): Marx, in his vision of communism, seeks a utopian equilibrium—where history ends, class struggles dissolve, and humanity lives in harmony. Yet history shows that struggle is ceaseless, and this equilibrium remains elusive.

Conclusion:#

You would tie this all together by suggesting that these prototypes serve as fractal patterns—self-similar in their structure across domains, appearing throughout history in various forms. The strategy-payoff-equilibrium framework can be applied to analyze not just art and history but can even serve as a predictive model in personal and societal contexts.

By imbuing life’s events with these archetypal trajectories, we better understand the past, interpret the present, and navigate the future. Through this fractal-based, game-theoretic lens, you offer a robust narrative model for individuals and collectives alike, guiding us through the tides of uncertainty, joy, and inevitable disappointment.

Tuscany Remix#

Here’s your restructured Chapter 2 using Dante’s framework of Inferno (non-cooperative strategy), Purgatorio (iterative progress), and Paradiso (cooperative ideal):

Inferno: Strategy Amidst Non-Cooperative Cosmic Elements#

Nietzsche’s critique of European culture is full of references to collapse, rebellion, and eventual return to old structures. He saw the Romantic spirit as fundamentally rebellious—defiant of traditional values and oppressive institutions. However, the Romantic drive for freedom often collapses under its own contradictions, leading to a return to familiar, authoritarian systems. This mirrors the adversarial strategies in Dante’s Inferno, where defiance against divine order results in isolation and suffering. Each sinner in the Inferno is trapped in a non-cooperative game with fate—stuck in a loop of their rebellion without a return to equilibrium.

Mozart’s Don Giovanni is a powerful artistic reflection of this. Don Giovanni rebels against moral and social order, fully embracing his desires and rejecting authority. From a Nietzschean perspective, he is not truly “romantic” because he never collapses or seeks redemption. He refuses to repent even in the face of eternal damnation, embodying an adversarial strategy in the non-cooperative cosmic order. He is the quintessential anti-hero—aligned with a tragic vision of Inferno, refusing the arc of surrender and return.

In this sense, Don Giovanni does not fit the typical Romantic cycle. He is more of a Dionysian figure, rebelling to the end, embracing the abyss. His story, like those in Dante’s Inferno, is one of non-cooperation with the divine order, a perpetual rebellion without reconciliation.

Purgatorio: Iterative Becoming#

In Purgatorio, the game is no longer purely adversarial but becomes a process of self-improvement and iteration. Here, souls are in an iterative state of “becoming”—working through their faults in a cooperative, though difficult, process of atonement. This is where progress and transformation occur through repeated cycles, moving ever closer to equilibrium.

Visually, Leonardo da Vinci’s meticulous studies and Bach’s structured compositions mirror this process. Da Vinci’s mathematical precision and Bach’s harmonic balance show a commitment to understanding and organizing the world, but always with a sense of becoming. They reflect a methodical approach—an intellectual strategy aimed at transcending the chaos of the Inferno by embracing iterative growth.

Dostoyevsky offers a literary reflection of this in works like The Gambler, where the odds of success and failure reflect the moral gray zones of life. His characters constantly calculate their chances—caught in an ongoing purgatorial cycle of betting, hoping, and trying again. This reflects the struggle of Purgatorio, where the next step is never certain, but the process of becoming pushes them forward.

In Raphael’s School of Athens, we see a harmonious coming together of diverse perspectives. No single philosopher dominates the scene; instead, it represents an intellectual iteration where truth emerges not from one, but from many viewpoints. Similarly, Mozart’s operas like The Marriage of Figaro revel in the chaotic, iterative nature of human relationships, where nothing is set in stone, and everything is subject to change and negotiation.

Nietzsche’s philosophy of eternal recurrence also reflects this iterative process. Life repeats in cycles, and the challenge is to accept and even love this repetition—embracing the iterative nature of existence as part of the cosmic game. Purgatorio is not a place of certainty but of possibility, where every iteration brings us closer to a more balanced state.

Paradiso: Idealized Destination#

Paradiso represents the final equilibrium—an idealized, cooperative destination where all strategies align harmoniously. Here, the souls have moved beyond the adversarial and iterative phases and arrived at a state of perfect cooperation with the divine. In this phase, the equilibrium is achieved, and there is no longer conflict or struggle.

Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam and David represent this aspirational ideal visually, where human potential reaches toward the divine. These works embody the balance of form, spirit, and ambition—equilibrium between the human and the cosmic. It’s the visual manifestation of an idealized, cooperative state where the imperfections of the human form are celebrated as part of the divine order.

Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony initially symbolized a revolutionary equilibrium—a world restructured through Napoleon’s heroism. However, as Beethoven realized Napoleon’s ambitions were not what he imagined, the ideal of revolutionary change crumbled. This reflects the difficulty of achieving equilibrium in the real world. But musically, Beethoven’s romantic ideals still strive for harmony and balance, even if the political reality disappoints.

Finally, Karl Marx envisioned the intellectual ideal of a cooperative equilibrium: communism. He saw history as a class struggle leading to the ultimate dissolution of conflict, where society would reach a harmonious state of equality. Though history has shown this ideal is far more complex, Marx’s vision remains a powerful example of striving for cooperative equilibrium—a Paradiso of social harmony.

Conclusion#

This chapter explores how Nietzsche’s critique of European culture and rebellion, as well as the artistic and intellectual archetypes of da Vinci, Bach, Dostoyevsky, and others, fit into Dante’s tripartite structure of strategy, iteration, and cooperation.

In Inferno, adversarial strategies dominate, with characters like Don Giovanni locked in eternal rebellion. In Purgatorio, the iterative process of becoming reflects the struggle toward self-improvement and reconciliation with chaos. Finally, in Paradiso, the idealized equilibrium represents the ultimate goal—whether in art, music, or philosophy—where human potential reaches a harmonious state of cooperation with the divine order.

By reframing this narrative through Dante’s structure, we gain a deeper understanding of these archetypes and their relevance to both personal and societal progress. Life itself becomes a journey through these stages, where strategy, iteration, and cooperation guide us toward the final destination.

This structure ties Nietzsche, Mozart, and other archetypes into Dante’s Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso framework, aligning the phases of struggle, becoming, and ultimate harmony with the broader themes of your essay. Let me know if you’d like to adjust anything further!