Stable#

Tatoos#

Tattoos function as a dynamic form of identity inscription, operating at the intersection of biological signal processing and social encoding. In the language of immunology and perception, we might define their role using the function w = 1/(1+X/Y), where X represents noise or molecular distractions, and Y represents the underlying signal or epitope. The human body, like a neural network, is constantly parsing its environment, distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant information. Tattoos, in this framework, represent a deliberate augmentation of the signal-to-noise ratio, often by increasing the weight of symbolic identity markers in social or criminal hierarchies.

At their core, tattoos compress information into an immediately interpretable visual format, providing an interface between the individual and the collective. They serve as an embodied ledger of personal history, cultural affiliation, and in many cases, defiance or allegiance. In Western societies, tattoos have undergone a transformation from markers of deviance to expressions of self-determined artistry. Yet, in certain ecosystems—most notably among criminal syndicates—tattoos remain a coded language, where each marking signifies rank, allegiance, and even betrayal. Nowhere is this function more pronounced than in the Russian criminal underworld, where tattoos are not mere adornments but a biological and ideological contract.

In the Russian mob—particularly the Vory v Zakone, or “Thieves in Law”—tattoos function as a lexicon of power. Each design encodes an entire biography: a church steeple might signal the number of prison terms served, a spider crawling up the arm denotes active criminal status, while a dagger through the neck might announce a conviction for murder. These tattoos function as both credentials and territorial markers, akin to immunological epitopes signaling self versus non-self. Within this closed system, a false tattoo—one claimed without having earned its corresponding status—can lead to immediate and often lethal consequences, much like an immune response attacking foreign tissue. The Vory use tattoos to eliminate ambiguity, ensuring that identity is embedded in the flesh itself, immutable and verifiable.

Yet tattoos also serve a secondary function: they are not merely markers of past deeds but tools for strategic deterrence. A tattooed criminal announces their position in the hierarchy to both allies and potential rivals. In this sense, the ink operates as an adaptive advantage within an adversarial equilibrium, deterring unnecessary challenges while reinforcing the existing power structure. This is particularly relevant in prison environments, where the body becomes both a battlefield and a billboard, an organic surface onto which one’s history and credibility must be inscribed. The absence of tattoos in such an environment is itself a declaration—of either power or vulnerability, depending on the context.

The Russian mob’s system of tattooing represents a kind of biological hacking of perception. By integrating symbolic meaning directly into the body, it circumvents the usual cognitive processes of trust-building and recognition, enforcing a streamlined, high-fidelity identification system. This is reminiscent of immunological processes where pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) immediately classify molecules as friend or foe, bypassing slower deliberative mechanisms. The efficiency of the system is precisely why it remains brutally effective: one does not need to inquire about another’s status when the information is already etched into their skin.

In contrast, modern commercial tattooing operates under a very different equilibrium. The transformation of tattoos from clandestine criminal codes to mainstream aesthetics represents a fundamental shift in the function of body modification. In consumerist societies, tattoos are increasingly personalized and fragmented, reflecting individual narratives rather than collective identities. This transition from high-signal, high-stakes encoding to diffuse, personal expression mirrors a shift from adversarial equilibrium to an iterative one—where tattoos no longer serve as rigid markers of identity but as evolving symbols of self-construction.

The question remains whether this dilution of meaning will eventually erase the potency of tattooing as a social signal. In a world where tattoos no longer carry high-stakes credibility, their role in establishing identity may become purely decorative, reducing Y (signal strength) and increasing X (noise). When every person can inscribe any history upon themselves without consequence, the system shifts away from embodied verification toward a looser, more fluid form of meaning-making. Whether this shift represents liberation or entropy depends on one’s perspective.

In the end, the tattoo—whether in the context of the Russian mob or Western self-expression—remains a manifestation of the fundamental human drive to mark one’s passage through time, to externalize memory onto the body itself. The difference lies in the weight of that inscription. In some contexts, ink is merely ink; in others, it is a sentence, a contract, a battle scar. The interplay between signal and noise, between authenticity and artifice, defines the power of the mark. And as long as human societies operate within hierarchical structures, tattoos will continue to serve as both ornament and oracle, as noise and as meaning.

The necessity of tattoos as markers of identity emerges in environments where conventional signals—appearance, language, and name—cease to suffice. This shift occurs at the intersection of historical upheaval, social fragmentation, and adversarial power structures. The tattoo, once ornamental or symbolic, becomes essential when trust erodes and identity verification demands an immutable, bodily inscription. Across history, the moments when tattoos became indispensable reveal the limits of linguistic and visual identification in conditions of war, exile, criminality, and forced belonging.

One of the earliest documented uses of tattoos as compulsory identity markers appears in the ancient world. In Rome, slaves and criminals were branded or tattooed to signify their status permanently. This practice arose from a need to make social stratification irrefutable. A name could be changed, dialects could be learned or masked, and appearances could be altered, but a tattoo embedded in the skin served as an undeniable, lifelong designation. The necessity of such branding intensified in the context of large, mobile empires where bureaucratic oversight was weak, and the movement of people across regions made visual or linguistic identification unreliable.

In medieval Japan, criminal tattooing, known as “irezumi kei,” functioned as a permanent mark of dishonor. Rather than execution, criminals were punished with ink, ensuring their exclusion from mainstream society. This necessity arose from the failure of written or oral records to provide persistent identification. A man who committed a crime in one province could vanish and reemerge elsewhere with a new name, a different manner of speech, and altered dress. Tattoos disrupted this fluidity, making deception impossible. The tattooed body itself became a living registry of social transgression, and in response, outcast groups such as the yakuza appropriated the practice, transforming their marks into emblems of defiant belonging.

The transformation of tattoos from instruments of control to symbols of allegiance recurs throughout history, but it is most pronounced in contexts where identity must be forcibly reaffirmed. The Nazi concentration camps of World War II represent one of the most harrowing examples of tattooing’s necessity under extreme conditions. The SS implemented systematic tattooing on prisoners, particularly in Auschwitz, to replace the inefficiency of paper records. In an environment where death and disappearance were routine, written names became meaningless; inked numbers etched into flesh provided the only durable proof of existence. Here, tattooing ceased to be a choice and became an act of bureaucratic violence, reducing human identity to an irreversible, dehumanized cipher.

Beyond systems of oppression, tattoos became necessary in criminal underworlds where language and conventional markers of identity could not withstand deception. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Russian Vory v Zakone—the “Thieves in Law.” In Soviet-era prisons, tattoos operated as a codified language of rank, experience, and criminal pedigree. Names were unreliable; informants and double agents could assume false identities, and spoken language was subject to lies. Tattoos, however, were earned. A thief bearing a star on his chest was marked as an elite member of the underworld. Those who falsely adorned themselves with such symbols faced lethal retribution. In this context, tattoos became an immutable form of biological encryption, ensuring that status could not be forged or faked.

The necessity of tattoos also surfaces in contexts where cultural erasure threatens identity. Among indigenous Polynesians, particularly the Māori, the tradition of Tā moko ensured that lineage, achievements, and social standing were inscribed directly onto the skin. In colonial encounters, where European powers imposed assimilation, banning indigenous languages and traditional dress, tattoos became the final bastion of self-definition. Even when native names were replaced with Christian ones, and languages were suppressed, the inked patterns on the face and body remained as assertions of continuity and defiance.

In the contemporary world, the necessity of tattoos as a verification tool remains in select domains—most notably in organized crime, military units, and certain subcultures where identity must be beyond doubt. Gang affiliations, military brotherhoods, and extremist groups often rely on tattoos as rites of passage, signifying unbreakable commitment. In such environments, words and oaths are insufficient; only inked skin guarantees allegiance.

Ultimately, the necessity of tattoos arises when identity must be made indelible—when language falters, names become unreliable, and appearances deceive. Whether imposed by power or embraced in defiance, the tattoo endures as the final recourse for proving who one is, when all other means fail.

Ecosystem#

The scientific enterprise in clinical medicine and public health presents itself as a disciplined search for knowledge, yet beneath its methodical facade lies an ecosystem riddled with contradictions, inefficiencies, and deeply embedded structural biases. It is an organism of paradoxes: at once rigorous and error-prone, innovative and conservative, visionary and myopic. The immune system offers a potent metaphor for this reality, illustrating how the scientific enterprise balances discovery with skepticism, adaptation with resistance, and progress with self-regulation. Like an immune network, the scientific endeavor operates through hierarchical layers of signal processing, from the early detection of anomalies to the ultimate resolution of systemic challenges. Yet, as with the immune system, malfunctions—whether in the form of scientific dogma, bureaucratic stagnation, or misaligned incentives—can lead to autoimmune dysfunctions that threaten the very progress science purports to achieve.

At its foundation, science seeks integration, much like the pericentral immune layer where recognition of self and non-self governs the body’s response to threats. The fundamental question of clinical science—what constitutes disease and what defines health?—mirrors the immune system’s incessant task of distinguishing between pathogen and commensal, between necessary intervention and overreaction. In public health, this tension is manifest in debates over population-level interventions versus individualized care. Just as the immune system must navigate an ecosystem of microbial inhabitants, determining when to tolerate and when to attack, public health must negotiate the trade-off between preventive mandates and personal autonomy. When does intervention become overreach? When does hesitation cost lives?

See also

Scientific Enterprise

Layered atop this foundation is the scientific decision-making process—akin to the neural-immune interface where pattern recognition receptors and innate lymphoid cells (PRRs and ILCs) filter raw data into actionable information. In research, this manifests as the peer-review process, the gatekeeping of medical journals, and the hierarchies of academic influence. Here, the system is simultaneously indispensable and deeply flawed. Bias in publication, the inertia of entrenched paradigms, and the preference for positive results over negative findings create distortions in what is considered valid knowledge. Much like an immune system that might tolerate chronic infection while launching an exaggerated response to harmless stimuli, the scientific apparatus often dismisses unconventional breakthroughs while entrenching established but suboptimal paradigms. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated this in real time: early skepticism toward airborne transmission, the politicization of mask efficacy, and the slow adaptation to emerging data revealed the limits of a system that prides itself on agility but is often bound by its own conservatism.

Clinical decision-making operates at the Choisis layer, akin to the adaptive immune system where CD4+ and CD8+ T cells orchestrate targeted responses. In medicine, the reliance on evidence-based guidelines mirrors the way immune cells rely on memory to recognize past infections. Yet, this approach has an inherent flaw: it assumes that prior knowledge is static and universally applicable. The rigid adherence to protocols often stifles the very innovation that defines science. The challenge, then, is one of calibration—how to balance the wisdom of accumulated knowledge with the necessity for adaptation in the face of novel challenges. The failure of many clinical trials to account for heterogeneity in patient populations—treating all comorbidities as equal, standardizing interventions in a manner that overlooks individual variation—reveals an immune-like rigidity in the medical system. If the immune system were to follow such a path, it would succumb to chronic infection or autoimmune attack, unable to fine-tune its response to the nuances of its environment.

The Deviens layer represents the space where medicine confronts its consequences—where adverse events, unforeseen complications, and the evolution of disease force a reassessment of prior assumptions. Here, the analogy to immune tolerance and regulatory mechanisms becomes stark: failure to moderate inflammation leads to chronic disease, just as failure to critically evaluate the limitations of scientific models leads to medical stagnation. The opioid epidemic, for example, represents a catastrophic failure at this layer: an intervention initially celebrated as a humane response to pain management spiraled into a crisis precisely because the medical community failed to anticipate the long-term consequences. Similarly, the slow recognition of racial disparities in clinical outcomes highlights how the medical establishment, like an immune system that misidentifies threats, often exacerbates systemic inequities by failing to correct its own biases.

Distributed Analytics

Centralized databases with PIs as vanguards should be considered prime target

The final layer, M’élève, is where outcomes are ultimately measured—where medicine must face the reality of its impact. Mortality, organ failure, frailty, and long-term disability serve as the brutal, unfiltered metrics of success or failure. In this sense, public health functions much like an evolved immune response: it assesses past failures, reconfigures strategies, and attempts to predict future threats. But as with all complex systems, its effectiveness is limited by incomplete information, political interference, and competing interests. The challenge of scientific medicine is not merely to gather data but to synthesize it in a way that translates into meaningful, actionable, and just outcomes. The history of clinical research is littered with cautionary tales—of overconfidence in statistical models, of misplaced faith in technologies that exacerbated disparities, of medical interventions that promised progress but delivered unintended harm.

Beyond its internal mechanics, the scientific enterprise is also an ecosystem, shaped by forces beyond its control. The interaction between researchers, clinicians, patients, regulatory agencies, and commercial interests creates an environment where knowledge production is neither pure nor objective. The front-end simplicity of a clinical application—a tool for patient engagement, risk assessment, or decision support—belies the intricate, often opaque back-end complexities that determine its functionality. Data governance, privacy regulations, institutional review boards, and the labyrinthine ethics of informed consent form a substrate of competing priorities, much like an immune network balancing surveillance, tolerance, and activation. Here, the question is not just what the science says, but who gets to interpret it, who funds it, and who benefits from its conclusions.

If we accept that science, like the immune system, is a dynamic, self-regulating network, then its success depends on its ability to evolve, to learn from its past mistakes, and to correct its course without succumbing to inertia or self-destruction. The failures of the scientific enterprise are not mere accidents; they are symptoms of deeper structural inefficiencies—flaws in feedback loops, misaligned incentives, and an epistemic culture that often resists correction. In this light, the path forward is neither blind faith in scientific authority nor wholesale rejection of its methods but a rigorous, unrelenting interrogation of its processes. Just as the immune system must navigate between action and restraint, so too must science constantly recalibrate its balance between certainty and skepticism, innovation and humility, knowledge and doubt.

In the end, the scientific enterprise is only as robust as its capacity for self-correction. And like an immune system, when it fails to distinguish between meaningful intervention and self-inflicted harm, it risks becoming its own worst enemy.

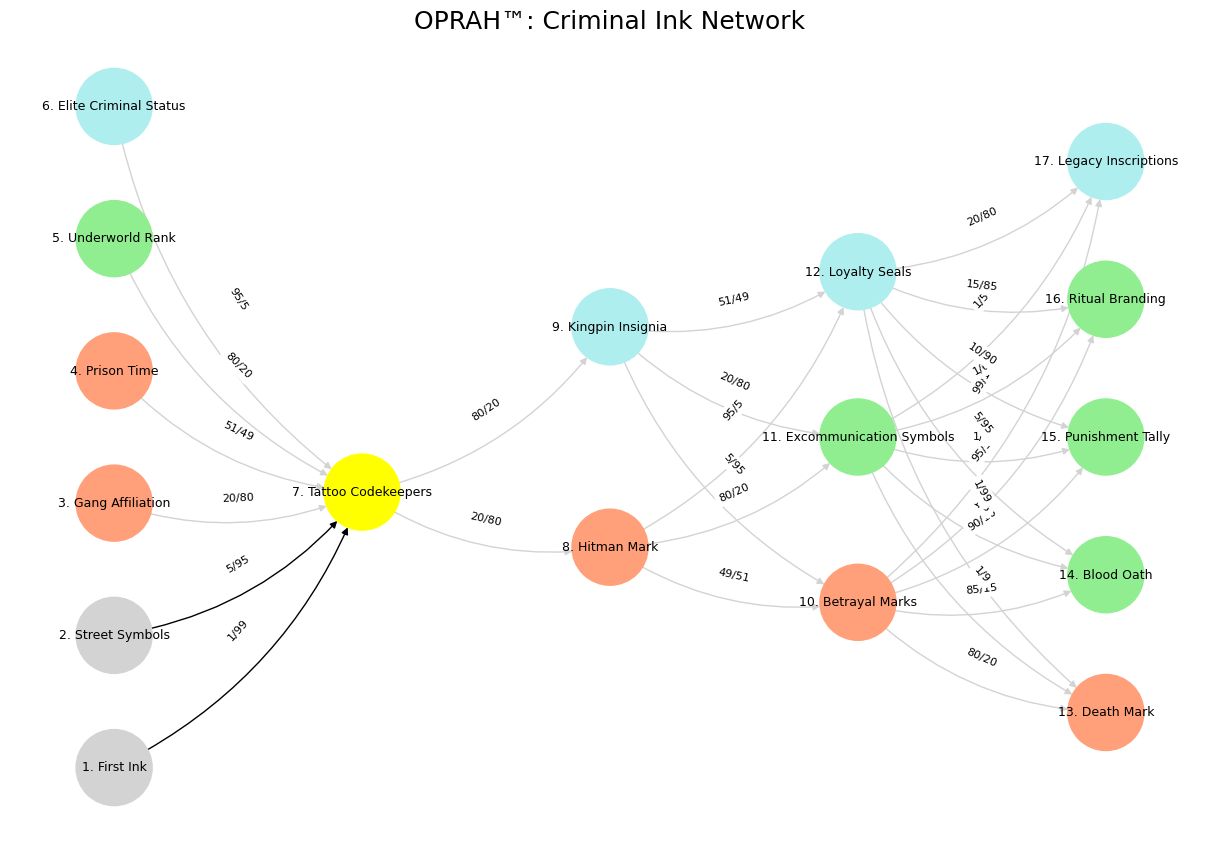

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the relabeled network layers with tattoo-world labels

def define_layers():

return {

'Initiation': ['First Ink', 'Street Symbols', 'Gang Affiliation', 'Prison Time', "Underworld Rank", 'Elite Criminal Status'],

'Recognition': ['Tattoo Codekeepers'],

'Authority': ['Hitman Mark', 'Kingpin Insignia'],

'Regulation': ['Betrayal Marks', 'Excommunication Symbols', 'Loyalty Seals', ],

"Execution": ['Death Mark', 'Blood Oath', 'Punishment Tally', 'Ritual Branding', 'Legacy Inscriptions']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Tattoo Codekeepers'],

'paleturquoise': ['Elite Criminal Status', 'Kingpin Insignia', 'Loyalty Seals', 'Legacy Inscriptions'],

'lightgreen': ["Underworld Rank", 'Excommunication Symbols', 'Blood Oath', 'Ritual Branding', 'Punishment Tally'],

'lightsalmon': ['Gang Affiliation', 'Prison Time', 'Hitman Mark', 'Betrayal Marks', 'Death Mark'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights

def define_edges():

return {

('First Ink', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '1/99',

('Street Symbols', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '5/95',

('Gang Affiliation', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '20/80',

('Prison Time', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '51/49',

("Underworld Rank", 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '80/20',

('Elite Criminal Status', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '95/5',

('Tattoo Codekeepers', 'Hitman Mark'): '20/80',

('Tattoo Codekeepers', 'Kingpin Insignia'): '80/20',

('Hitman Mark', 'Betrayal Marks'): '49/51',

('Hitman Mark', 'Excommunication Symbols'): '80/20',

('Hitman Mark', 'Loyalty Seals'): '95/5',

('Kingpin Insignia', 'Betrayal Marks'): '5/95',

('Kingpin Insignia', 'Excommunication Symbols'): '20/80',

('Kingpin Insignia', 'Loyalty Seals'): '51/49',

('Betrayal Marks', 'Death Mark'): '80/20',

('Betrayal Marks', 'Blood Oath'): '85/15',

('Betrayal Marks', 'Punishment Tally'): '90/10',

('Betrayal Marks', 'Ritual Branding'): '95/5',

('Betrayal Marks', 'Legacy Inscriptions'): '99/1',

('Excommunication Symbols', 'Death Mark'): '1/9',

('Excommunication Symbols', 'Blood Oath'): '1/8',

('Excommunication Symbols', 'Punishment Tally'): '1/7',

('Excommunication Symbols', 'Ritual Branding'): '1/6',

('Excommunication Symbols', 'Legacy Inscriptions'): '1/5',

('Loyalty Seals', 'Death Mark'): '1/99',

('Loyalty Seals', 'Blood Oath'): '5/95',

('Loyalty Seals', 'Punishment Tally'): '10/90',

('Loyalty Seals', 'Ritual Branding'): '15/85',

('Loyalty Seals', 'Legacy Inscriptions'): '20/80'

}

# Define edges to be highlighted in black

def define_black_edges():

return {

('First Ink', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '1/99',

('Street Symbols', 'Tattoo Codekeepers'): '5/95',

}

# Calculate node positions

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

black_edges = define_black_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Create mapping from original node names to numbered labels

mapping = {}

counter = 1

for layer in layers.values():

for node in layer:

mapping[node] = f"{counter}. {node}"

counter += 1

# Add nodes with new numbered labels and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

new_node = mapping[node]

G.add_node(new_node, layer=layer_name)

pos[new_node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with updated node labels

edge_colors = []

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in mapping and target in mapping:

new_source = mapping[source]

new_target = mapping[target]

G.add_edge(new_source, new_target, weight=weight)

edge_colors.append('black' if (source, target) in black_edges else 'lightgrey')

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color=edge_colors,

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("OPRAH™: Criminal Ink Network: Ukubona Ubuntu", fontsize=18)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 40 Icarus represents a rapid, elegant escape from the labyrinth by transcending into the third dimension—a brilliant shortcut past the father’s meticulous, earthbound craftsmanship. Daedalus, the master architect, constructs a tortuous, enclosed structure that forces problem-solving along a constrained plane. Icarus, impatient, bypasses the entire system, opting for flight: the most immediate and efficient exit. But that’s precisely where the tragedy lies—his solution works too well, so well that he doesn’t respect its limits. The sun, often emphasized as the moralistic warning, is really just a reminder that even the most beautiful, radical solutions have constraints. Icarus doesn’t just escape; he ascends. But in doing so, he loses the ability to iterate, to adjust dynamically. His shortcut is both his liberation and his doom. The real irony? Daedalus, bound to linear problem-solving, actually survives. He flies, but conservatively. Icarus, in contrast, embodies the hubris of absolute success—skipping all iterative safeguards, assuming pure ascent is sustainable. It’s a compressed metaphor for overclocking intelligence, innovation, or even ambition without recognizing feedback loops. If you outpace the system too fast, you risk breaking the very structure that makes survival possible. It’s less about the sun and more about respecting the transition phase between escape and mastery.#