Theomarchy & Principalities, y#

Geotheology: Reclaiming the Sacred Landscape of Thought#

The idea of geotheology, a study of how geography and theology intertwine, offers profound generativity for understanding human spirituality and its connection to space, place, and direction. Unlike geopolitics, which divides and manipulates the Earth’s surface into zones of power and influence, geotheology opens a contemplative dialogue about how landscapes shape our sense of the divine and how religious narratives, in turn, remap geography. This vision of geotheology is not only a means of exploring ancient traditions but also a framework for examining the challenges of modernity and even the possibilities of a future beyond Earth.

Sacred Orientations and the Geometry of Faith#

One of the most universal elements of human spirituality is its orientation toward specific directions. Many cultures and religions place the East at the heart of their cosmological framework. For Christians, the East symbolizes the resurrection, with early church altars facing the rising sun to anticipate the return of Christ. Muslims direct their prayers toward Mecca, but for vast populations in the Americas and Europe, this means turning east. Hindus rise early to greet the sun as Surya, performing the Surya Namaskar, while Buddhist stupas and Zen temples are often built to align with the morning light. The significance of direction, then, becomes more than practical—it becomes theological, a sacred geometry etched into human rituals and beliefs.

Yet sacred orientations do not stop with the East. Other directions hold their own theological weight: westward movements in Christian pilgrimages echo Christ’s journey toward Jerusalem, while Indigenous peoples often conceive of the four cardinal directions as embodying spiritual forces in balance. Geotheology, as a field, would map these directional theologies across cultures, offering a comparative framework to understand the ways in which humanity’s spiritual aspirations have been shaped by their horizons.

Fig. 1 Geotheology. Barry Aron Vann is an American author, speaker and retired Dean of Behavioral and Social Sciences at Colorado Christian University. A prolific writer, Vann has published on a wide range of geographic topics. He is most noted for his work in environmental perceptions and religious geography, in particular themes in which religious beliefs are associated with forming environmental perceptions and politicized regions such as Northern Ireland and the American Bible Belt. The conceptual framework Vann uses to analyse the relationship between belief systems and spaces, including nations and towns is called geotheology (the general relationship between the worship of the divine and spaces, including nations). Source: Wikipedia#

Landscapes of Revelation: Mountains, Rivers, and Deserts#

The Earth’s physical features—mountains, rivers, deserts—play a pivotal role in shaping religious narratives. The stark beauty of Mount Sinai in the Abrahamic traditions stands as a site of revelation, its rugged isolation symbolizing direct contact with the divine. Similarly, the Jordan River becomes a threshold between the wilderness and the promised land, while deserts feature prominently as spaces of testing and spiritual renewal, from the forty years of wandering in Exodus to Jesus’ forty days of fasting.

Geotheology would explore not just the symbolism of these landscapes but their lived reality. How does the daily sight of the Nile shape a people’s conception of abundance and order? How do the Himalayan peaks, looming over Hindu and Buddhist traditions, inspire the idea of transcendence? These are not mere metaphors but reflections of the human need to locate the sacred in the physical world.

Pilgrimage and the Sacred Journey#

Pilgrimage, as a practice, represents one of the most direct intersections between geography and theology. From the Hajj to Mecca to the Camino de Santiago, the physical act of moving toward a sacred destination is often seen as a metaphor for the soul’s journey toward enlightenment or salvation. But pilgrimage also transforms the landscape itself. Roads, markers, and monuments become embedded with meaning, turning mundane geography into a spiritual map.

Geotheology could examine how these sacred journeys function not just in traditional settings but in contemporary contexts. For instance, what does a pilgrimage look like in a hypermodern, globalized world? Can a journey to Silicon Valley be seen as a pilgrimage to a technological “Mecca,” or does the sacredness of pilgrimage require a certain timelessness?

Geotheology in the Anthropocene: Environmental Theology#

As humanity grapples with climate change and environmental degradation, geotheology offers a framework to reimagine our relationship with the natural world. Sacred groves, rivers, and mountains once revered as divine are now threatened by industrialization and exploitation. How can theology respond to the Anthropocene, an era in which humans have become a geological force?

Environmental theology, as a branch of geotheology, might draw on Indigenous cosmologies, which often see the Earth itself as alive and sacred. For example, the Maori concept of whenua (land) as both physical ground and ancestral connection challenges Western notions of land as property. Similarly, the Hindu reverence for the Ganges, despite its current pollution, suggests a potential for combining spiritual reverence with ecological action.

Beyond Earth: Geotheology on Mars#

Perhaps the most exciting frontier for geotheology lies not on Earth but in space. As humanity begins to explore Mars and other celestial bodies, new theological questions emerge. How would religions adapt to a world without the familiar cycles of sunrise and sunset? Would a Martian day, lasting 24.6 hours, disrupt the rhythms of prayer for Muslims, Jews, and others whose practices are tied to earthly time? Would the absence of traditional landscapes—mountains, rivers, forests—diminish the sense of the sacred, or would humanity find new ways to sacralize the Martian desert?

Mars could also inspire theological innovation. Imagine a Martian pilgrimage, where the act of journeying across barren plains mirrors the spiritual isolation of the soul seeking connection. Or consider the possibility of creating Martian temples, designed not to align with earthly cardinal directions but with constellations or other celestial phenomena visible from Mars. These questions force us to reimagine the relationship between faith and geography in ways that are both thrilling and unsettling.

Virtual Geotheology: Sacred Spaces in the Digital Age#

As the physical and virtual worlds increasingly overlap, geotheology must also grapple with the idea of sacred spaces online. Could a virtual Mecca, where millions of Muslims gather in a shared digital experience, hold theological meaning? Would a virtual Jerusalem, rendered in immersive detail, inspire the same reverence as the physical city?

Virtual geotheology could also explore how digital landscapes challenge traditional notions of sacred geography. For instance, does the absence of physicality in a virtual temple diminish its authenticity, or does the communal experience of shared prayer make it equally sacred? These questions blur the boundaries between geography, technology, and spirituality, offering fertile ground for theological reflection.

Toward a Manifesto for Geotheology#

Geotheology, as a discipline, has the potential to reshape how we understand the world and our place within it. By examining the intersections of geography and theology, it invites us to see the Earth—and beyond—not as inert matter but as a dynamic, sacred canvas on which human spirituality is inscribed. Whether we are mapping the sunrise rituals of ancient Japan, the pilgrimages of modern Muslims, or the potential for Martian theology, geotheology reminds us that the sacred is not confined to time or place. It is everywhere, waiting to be discovered, reimagined, and lived.

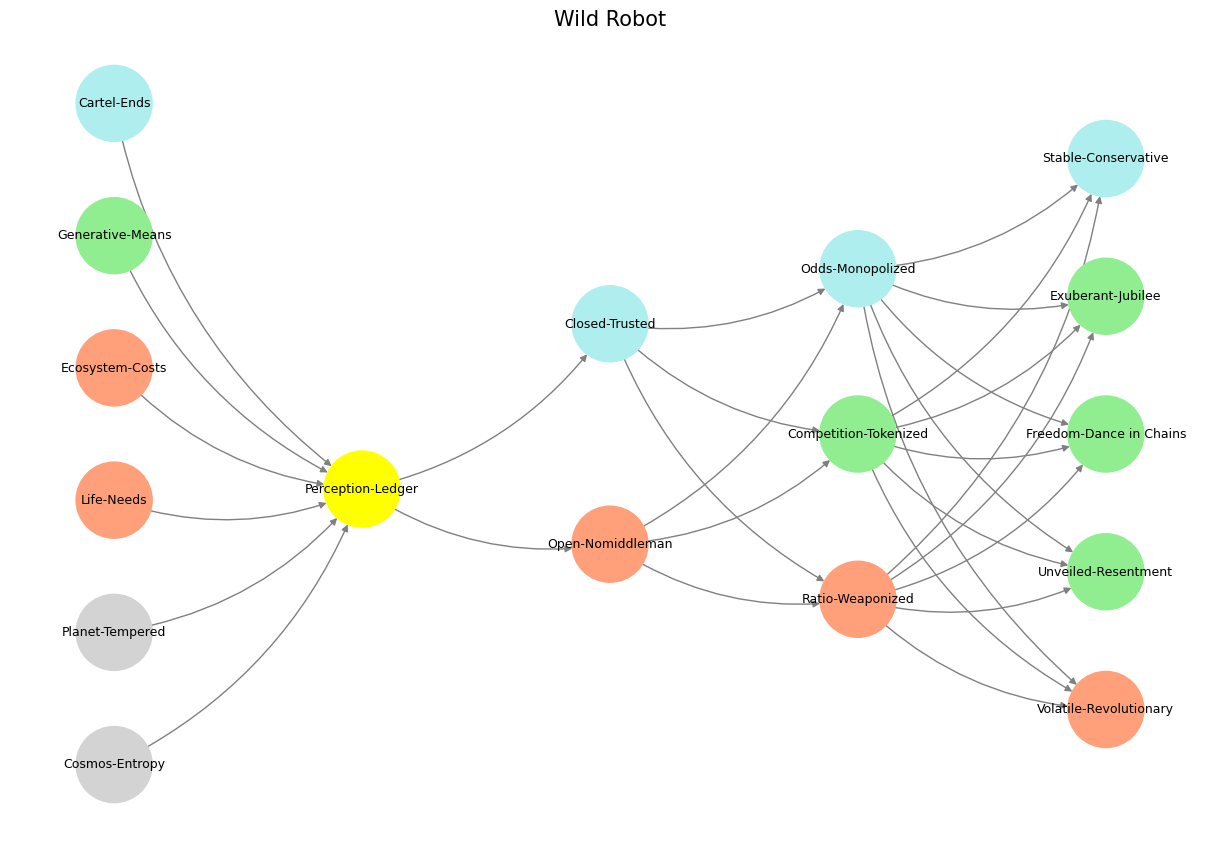

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'Planet-Tempered', 'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Generative-Means', 'Cartel-Ends', ], # Theomarchy

'Perception': ['Perception-Ledger'], # Mortals

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Fire

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Gamification

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Victory

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Perception-Ledger'],

'paleturquoise': ['Cartel-Ends', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Generative-Means', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Open-Nomiddleman',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Wild Robot", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 2 This book encapsulates the essence of ingenuity and progress—leveraging the cutting-edge tools of today to resolve humanity’s perennial challenges. It reflects an understanding of both innovation and resourcefulness, emphasizing the need to optimize what is already within our grasp– through the lens of “Wild Robot”. Theomarchy: A storm causes a Universal Dynamics cargo ship to lose ROZZUM robots, Mortals: which wash up on an uninhabited island. Fire: Only ROZZUM Unit 7134, nicknamed “Roz”, survives and is accidentally activated by wildlife. Gamification: Roz frightens the animals and injures herself while trying to help them, even after learning their language.Victory: Unable to find anyone needing her services, Roz signals for retrieval, but is struck by lightning and attacked by animals: While fleeing an aggressive grizzly bear, she accidentally crushes a goose nest, leaving one egg. Source: Wikipedia#