Freedom in Fetters#

Names are patterns, but they are also cadences. A name is not merely a static token of inheritance but a transition, a movement from one state to another, much like the cadences that structure music and language. If we see emotions as nodes and cadences as the edges between them, then naming is a kind of prosody, a rhythmic modulation that bridges past and present, structure and transformation. The five-year-old, without formal training in linguistics or machine learning, enacted something primal: he took an existing name and reconfigured it, preserving its core while reshaping its form. The question is whether this transformation was driven by an innate linguistic faculty, as Noam Chomsky might argue, or whether it was an emergent adaptation shaped by the accumulation of linguistic data, as Geoffrey Hinton’s neural networks would suggest.

They’ve discovered a much more deadly weapon of destruction–the wisecrack

– Somerset

Chomsky, in his decades-long battle against empiricist models of language acquisition, insists that human beings do not learn language from data alone. He proposes an innate faculty, a universal grammar embedded within the mind, which allows us to generate and comprehend language even in the absence of sufficient exposure to structured input. A five-year-old does not need exhaustive examples of naming conventions to invent KaD from Mr. D. The transformation arises not from raw statistical probabilities but from an underlying structure within the mind itself, an internal syntax that organizes language into recognizable forms even when the specific input is novel. The Zulu naming pattern—Mageba kaGumede, Ndaba kaMageba, Jama kaNdaba—reflects precisely this kind of internal structuring, a recursive syntax that seems to encode lineage through an implicit rule-based system. The five-year-old, without needing explicit instruction, re-created a similar structure. If this act of renaming is the product of an innate grammar, it lends weight to Chomsky’s argument: structure is not imposed from without, but generated from within.

Hinton, by contrast, would see this transformation as an instance of pattern recognition refined through exposure. The mind, like a neural network, is continuously updating its internal weights based on prior experience. The child may not have had an explicit training set of thousands of names, but he had been immersed in language, attuning to the statistical distributions and phonetic rhythms of naming conventions. The shift from Mr. D to KaD might then be interpreted as an extrapolation from available linguistic data, a probabilistic leap rather than an innate structural rule. Unlike Chomsky’s universal grammar, which is preconfigured, Hinton’s model assumes that meaning and structure emerge through layers of weighted associations, adjusted iteratively through exposure and feedback.

Yet, if all life is cadence, as you propose, then perhaps this debate is itself a false dichotomy. A cadence is not a rigid structure nor a purely statistical artifact—it is a movement, a transition from one state to another, from one name to another, from one generation to the next. The cadence from D to KaD is not merely an inheritance of phonemes, nor is it a blind stochastic reweighting of linguistic probabilities. It is an act of modulation, a shift in register that captures something deeper than either Chomsky’s innate grammar or Hinton’s learned patterns: it captures flow. This is what makes names different from fixed tokens. They are not inert markers but dynamic bridges, constantly reformulated through the interplay of structure, adaptation, and context.

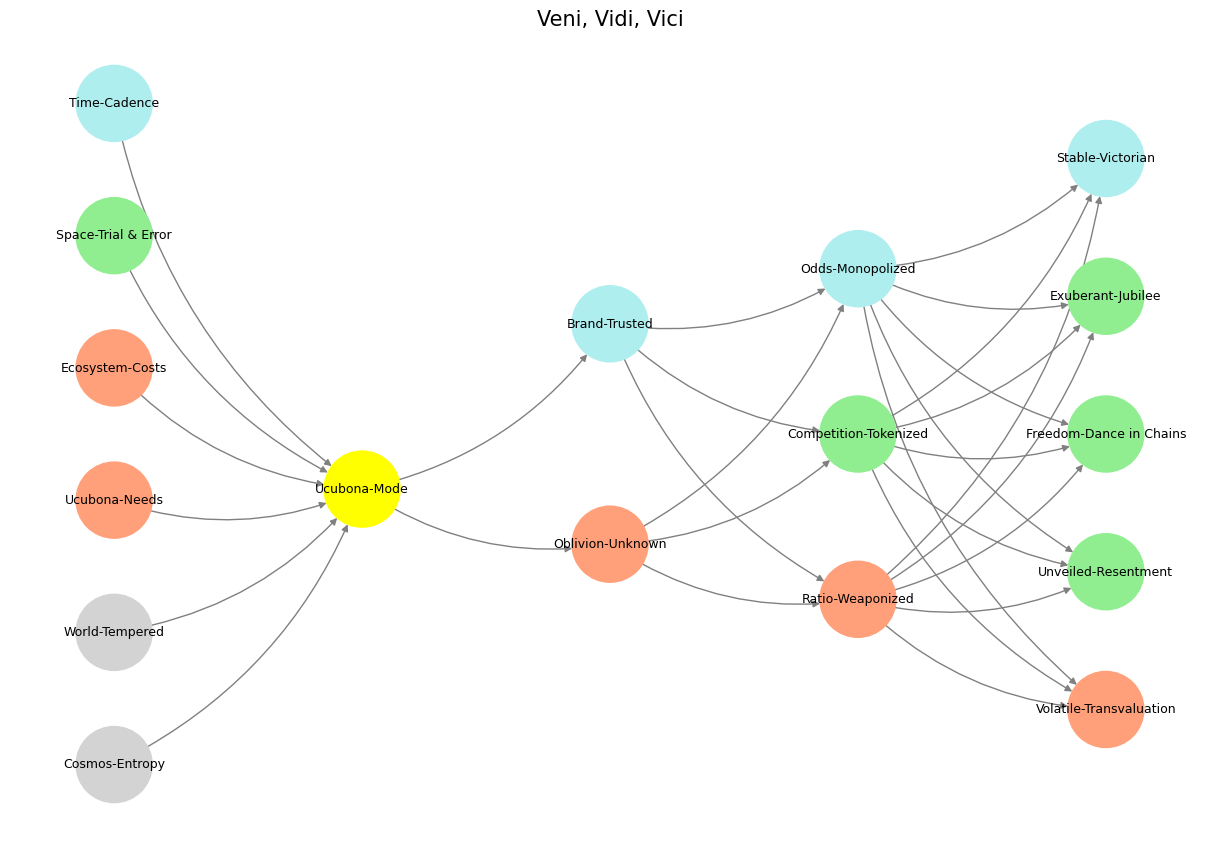

Fig. 24 The Next Time Your Horse is Behaving Well, Sell it. The numbers in private equity don’t add up because its very much like a betting in a horse race. Too many entrants and exits for anyone to have a reliable dataset with which to estimate odds for any horse-jokey vs. the others for quinella, trifecta, superfecta#

Zulu names encode this cadence at the generational scale: Mageba begets Ndaba, Ndaba begets Jama, Jama begets Senzangakhona, Senzangakhona begets Shaka. Each transition is both an act of preservation and transformation. The Soga practice, which does not adhere to strict linear inheritance but operates within a finite ancestral pool, introduces another type of cadence—one that cycles rather than follows a strict generational chain. The child’s renaming of his brother, then, is not simply a random act but a reenactment of these broader linguistic and cultural cadences, a microcosm of how inheritance itself oscillates between continuity and mutation.

If we take seriously the idea that emotions are nodes and cadences are the edges between them, then naming is a form of emotional cadence as well. The act of naming—or renaming—is never neutral. It carries with it connotations, affect, and social implications. The nurses at Akameda County, unable to pronounce Dhatemwa, stripped it down to Mr. D. A child, with a different set of heuristics, rebuilt it as KaD. These transformations are not just linguistic—they are affective, social, and deeply personal. They mark shifts not just in phonetics but in identity, in the way one is perceived and received by others. A name, then, is a conduit for cadence—not only across sounds, but across generations, across emotions, across the structures that define and redefine us.

So where does this leave the grand debate between Chomsky and Hinton? The truth is, language is neither purely innate nor purely learned; it is both, because it is cadence. There is a structure—yes—but that structure is not static. It modulates, shifts, and reinvents itself through use. The Zulu lineage system follows a recursive rule, but within that rule, transformation occurs. The Soga naming system operates on a different principle, but within its cycle, there is still a logic. And in the small but profound act of a child reshaping a name, we see both pattern and deviation, both the structure of inheritance and the freedom to alter it. Naming, like language itself, is a negotiation between what is given and what is made anew.

Chomsky is 97 and still arguing because the question remains open-ended, as all questions about cadence must be. The cadence of language, of inheritance, of identity—these are not static constructs but living processes. Just as KaD was an emergent name, so too is our understanding of language and thought ever-emergent, oscillating between the known and the unknown, between structure and transformation. In this sense, cadence is not just a feature of language—it is the very principle by which thought itself moves.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'World-Tempered', 'Ucubona-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Space-Trial & Error', 'Time-Cadence', ], # Veni; 95/5

'Mode': ['Ucubona-Mode'], # Vidi; 80/20

'Agent': ['Oblivion-Unknown', 'Brand-Trusted'], # Vici; Veni; 51/49

'Space': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Vidi; 20/80

'Time': ['Volatile-Transvaluation', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Victorian'] # Vici; 5/95

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Ucubona-Mode'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time-Cadence', 'Brand-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Victorian'],

'lightgreen': ['Space-Trial & Error', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Ucubona-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Oblivion-Unknown',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Transvaluation'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Veni, Vidi, Vici", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

#

Fig. 25 From a Pianist View. Left hand voices the mode and defines harmony. Right hand voice leads freely extend and alter modal landscapes. In R&B that typically manifests as 9ths, 11ths, 13ths. Passing chords and leading notes are often chromatic in the genre. Music is evocative because it transmits information that traverses through a primeval pattern-recognizing architecture that demands a classification of what you confront as the sort for feeding & breeding or fight & flight. It’s thus a very high-risk, high-error business if successful. We may engage in pattern recognition in literature too: concluding by inspection but erroneously that his silent companion was engaged in mental composition he reflected on the pleasures derived from literature of instruction rather than of amusement as he himself had applied to the works of William Shakespeare more than once for the solution of difficult problems in imaginary or real life. Source: Ulysses#