Veiled Resentment#

Names encode history. They are more than mere identifiers; they are vessels of lineage, cultural memory, and the subtle interplay between inheritance and reinvention. The list of Zulu names—Mageba kaGumede, Ndaba kaMageba, Jama kaNdaba, Senzangakhona kaJama, Shaka kaSenzangakhona—suggests a pattern of continuity, where each generation bears the imprint of the previous one. The syntax of these names follows an almost mathematical recursion, an unbroken chain of descent, where “ka” (son of) serves as both a grammatical and ontological bridge between past and present. Each name is not merely a designation but a point in a lineage that extends backward and forward in time, each son carrying the name of his father while adding his own distinct iteration to the sequence.

I married the first time to eliminate competition

– Monsieur Achille

This pattern, however, is not universally applied. The personal account disrupts the expected logic of transmission. The House of Dhatemwa, unlike the Zulu naming convention, does not follow a rigid structure of patronymic inheritance. Instead, it maintains a finite pool of ancestral names, from which a child’s name may be drawn but not necessarily derived in direct succession. This introduces an element of selection, perhaps even randomness, in contrast to the structured determinism of the Zulu model. Yet even within this more fluid system, there is a force that seeks pattern: the five-year-old brother who instinctively renames the narrator as KaD. Though unintended, the child restores a logic that mirrors the Zulu syntax—KaD, son of D. It is as if language itself, or some deeper cultural structure, asserts a need for continuity, for names to link generations, even in a system that does not explicitly mandate it.

The rejection of the given name and the spontaneous creation of a new one raises questions about how linguistic patterns emerge. Is there an innate human drive to impose structure? The five-year-old did not consciously follow an ancestral rule, yet his renaming mirrors a broader African tendency to encode lineage within names. If a name is too unfamiliar, too untethered from precedent, a new structure emerges organically. Perhaps this is why the nurses, unable to pronounce “Dhatemwa,” simply compressed it into “Mr. D,” reducing its complexity while preserving its essence. In the same way, the child’s mind, working with a different set of cultural materials, performed a similar reduction, distilling Dhatemwa into KaD. Both instances reflect a fundamental tension between the fluidity of names and the human impulse to make them fit into a discernible framework.

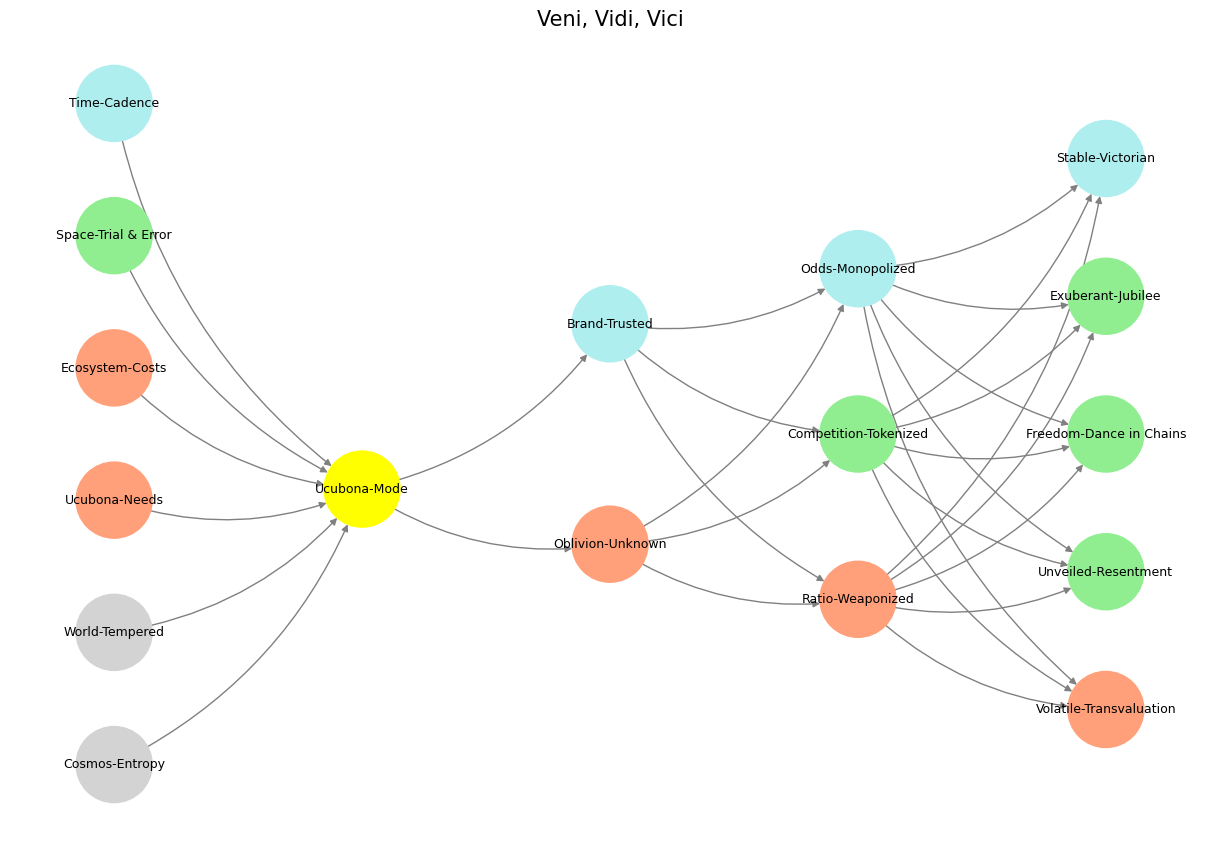

Fig. 21 The Next Time Your Horse is Behaving Well, Sell it. The numbers in private equity don’t add up because its very much like a betting in a horse race. Too many entrants and exits for anyone to have a reliable dataset with which to estimate odds for any horse-jokey vs. the others for quinella, trifecta, superfecta. The eternal recurrence of the same, as Nietzsche framed it, unfolds a cosmos devoid of beginning or end, an architecture where every output node circles back as input to an identical iteration, endlessly. In such a framework, the demand for moral purpose dissolves into absurdity. The cosmos, infinite in time and space, operates beyond binaries of good and evil, refusing to submit its vastness to human conceits of narrative closure. Yet Goethe’s defiance of moral demands, while celebrating the autonomy of the artist, rings hollow when confronted with the persistent itch for a conclusion, as Anthony Capella’s narrator discovers. To demand purpose from art, perhaps, is not to ruin it, but to humanize it, to tether infinite loops of meaning to a finite self yearning for understanding. In rejecting moral purpose, we may resist simplifying complexity, but we also risk severing art from its audience—an audience that, like Capella’s Victorian memoirist, craves resolution, even if only to satisfy itself. And so, while Nietzsche’s cosmos tumbles through its eternal recurrence, it must tolerate those who insist on finding lessons, a phenomenon less a contradiction than an inevitable consequence of human architecture mirroring the infinite. What have we learned? Perhaps only that the output of one iteration can be both conclusion and renewal, endlessly oscillating between the finite and the infinite.#

Yet names do more than merely preserve the past; they also prescribe futures. Shaka kaSenzangakhona is not just the son of Senzangakhona—he is Shaka, a singular historical force whose name became emblematic of power, transformation, and rupture. The lineage is there, but it is not enough to define him. Similarly, KaD is both an assertion of continuity and an act of rebellion, a remapping of identity on the child’s own terms. Naming, then, is a battleground between inheritance and invention, tradition and deviation. It encodes not only where one comes from but also how one is received by others, how one is transformed through linguistic, cultural, and historical filters.

This tension between the rigid and the fluid, the given and the chosen, plays out across societies. Among the Zulu, names function as historical markers, compressing entire genealogies into a single utterance. Among the Soga, the practice is less deterministic but still guided by the echoes of ancestral patterns. Across both, the fundamental impulse remains: to shape identity through language, to impose structure where none exists, or to subvert structure when it feels too confining. What remains constant is the idea that a name is never just a name—it is an inheritance, a negotiation, a prophecy.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'World-Tempered', 'Ucubona-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Space-Trial & Error', 'Time-Cadence', ], # Veni; 95/5

'Mode': ['Ucubona-Mode'], # Vidi; 80/20

'Agent': ['Oblivion-Unknown', 'Brand-Trusted'], # Vici; Veni; 51/49

'Space': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Vidi; 20/80

'Time': ['Volatile-Transvaluation', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Victorian'] # Vici; 5/95

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Ucubona-Mode'],

'paleturquoise': ['Time-Cadence', 'Brand-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Victorian'],

'lightgreen': ['Space-Trial & Error', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Ucubona-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Oblivion-Unknown',

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Transvaluation'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Veni, Vidi, Vici", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 22 Vet Advised When to Sell Horse. Right after an outstanding performance. Because you want to control how its perceived, the narrative backstory, and how its future performance might be imputed. Otherwise, reality manifests with point and interval estimates. This is the subject matter of the opening dialogue in Miller’s Crossing.#