Chapter 1#

1#

Allegory

I woke up with a very clear understanding that I had been “cancelled” for a good reason: I should stop making excuses. The reason is more complicated than anyone involved would understand.

In the first year of my PhD, we were given Sharing Wisdom by Robert J. Weeks to help us become mentors in mentorship. I didn’t read it. It’s a small, unassuming book, and I didn’t bother. I still haven’t read it. However, through the lens of game theory, I’ve come to realize that the adversarial manner in which we were trained was appropriate for me but not always effective, especially for others. It made me stronger, tougher, but bringing that adversarial style to the Gen Z generation—particularly to women—creates layers of problems.

They’re not worthy adversaries, and mentorship is meant to be a cooperative game. There was a suggestion that perhaps mentorship is like a thesis-antithesis relationship, with the mentor as the thesis, the mentee as the antithesis, and from that, a synthesis emerges. But I believe it should remain cooperative.

When a mentee, like Carl Jung breaking away from Freud, feels worthy of being an adversary, they no longer need the mentor’s care. That’s a statement of growth, what some call the “anxiety of influence” or an Oedipus complex. Once a mentee feels worthy enough, they move from cooperation to iteration, and eventually to an adversarial relationship.

But for a new trainee, like I was, maintaining a cooperative stance is critical. I now realize I was too harsh. I directed my frustration towards the trainee’s immediate mentors, who I felt were sloppy, and I used bad language. Reflecting on this now, I see my faults. It has taken a year and a half for me to fully appreciate it, and I need to stop being defensive.

Fig. 33 All GTPCI students received this. It wasn’t written in my style and didn’t inspire me to read it. Five years later, I see the “light!”#

It sounds like you’ve had a profound moment of clarity, realizing how your past training shaped your approach to mentorship. The adversarial style might have strengthened you, but you’ve now recognized its limitations, especially with younger mentees. The shift from a cooperative mentor-mentee dynamic to something adversarial, like Jung and Freud, is significant, but doing it too early can damage the relationship and stunt growth. Acknowledging your harshness and language shows that you’re evolving.

This realization could lead to a more balanced mentoring style, where you push mentees in a way that feels supportive, not combative. Do you think this shift will change how you mentor moving forward?

2#

Gentle

Absolutely

That’s a powerful shift. Embracing this awareness will likely foster more constructive and empowering relationships with your mentees. Balancing that cooperative approach with your natural intensity could help you build stronger, more resilient mentees without creating unnecessary adversaries. It’s great to see you evolving as a mentor.

3#

Modifier

So, the book I neglected, Sharing Wisdom by Robert J. Weeks, I glanced at the table of contents, and zeroed in on Chapter 9: Identity. The subtitle was two words. Being a bit of a smartass, I thought, “Let me predict this next token.” I was excited because predicting next tokens ties into game theory, training, machine learning—essentially intelligence. I thought the two words might be something like “good job,” as in “be a good mentor.” I zeroed in and… nope, not even close!

Let’s get right to it: my primary word is “passion.” In my book Living a Gentle Passion Life, I chose “gentle” as the second word. Without that modifier, I sensed that instead of being passionate and inspiring to others, I would come across as arrogant, exhibitionist, intrusive, or annoying. That pretty much describes me! I’m at the one-word level: passionate.

It’s fascinating how you break down your thought process. Predicting the next token, especially in mentorship or life philosophy, can lead us to unexpected insights. Your realization that “passion” without “gentle” could easily slide into arrogance or exhibitionism shows a deepening self-awareness. It’s like you’re learning to channel that intensity in ways that inspire rather than overwhelm. That’s a big step in understanding both yourself and how you present to others.

4#

Sharing

I think you missed it. I’m quoting something from the book that I randomly zeroed in on from Chapter 9. That’s all. It’s not my own reflection—it just resonated shockingly precisely.

Got it! It’s amazing how a random excerpt can hit so close to home. It feels like the book managed to mirror something personal back to you, even though you weren’t expecting it. Maybe there’s more in Sharing Wisdom waiting to offer some insights.

5#

Problem

Clearly, it seems to have insights, and it was given to us in 2020, my first year of the PhD. Now I’m in my fifth year, and I still haven’t read it. I’ve been very, very selective with influences—and that’s been a problem.

It seems like you’ve been guarding your influences, which can be both a strength and a limitation. Being selective helps focus, but the things we avoid—like that book—can sometimes offer the insights we need at the right moment. Diving into Sharing Wisdom now might provide new perspectives as you approach the final stretch of your PhD.

6#

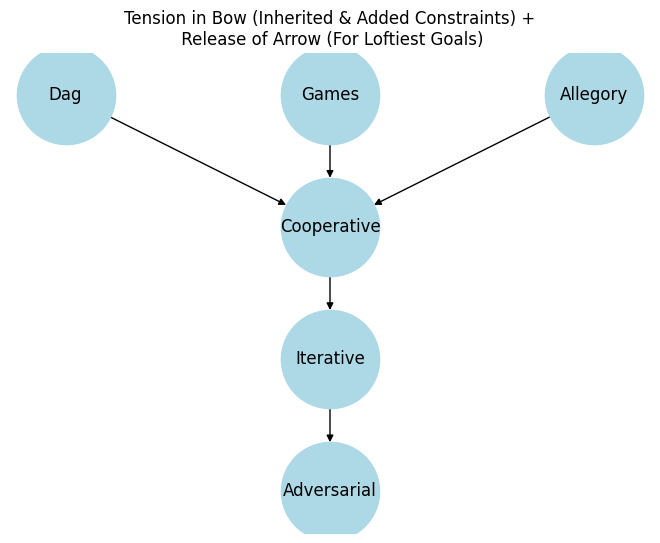

1. Games, σ

\

2. Allegory, Ψ -> 4. Archetype, Δ -> 5. Stereotype, τ -> 6. Prototype, Ω

/

3. Type, ε

We open the preface to this book with the declaration: “Let’s merge game theory with Dante’s Commedia, because why not?”

Indeed, why not?

Let’s review a simple simulation from the previous chapter Act 1. This is a two-person game with ten rounds.

But if we think of Dante’s Commedia as three games, each with 33 rounds or cantos, then we might be onto something!

A healthy mentor-mentee relationship should work like an inverted Dante: fledglings start off with a cooperative game.

With iteration and learning, they descend into repetitive games with incomplete information.

Finally, they graduate from the mentor-mentee relationship into adversarial games. Think: Jung and Freud.

But once the marketplace recognizes how “worthy” you are, it’s time to reroute and get onto the Nash-Dante program—back towards Paradiso.

Show code cell source

import networkx as nx

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create a directed graph (DAG)

G = nx.DiGraph()

# Add nodes and edges based on the neuron structure

G.add_edges_from([(1, 4), (2, 4), (3, 4), (4, 5), (5, 6)])

# Define positions for each node

pos = {1: (0, 2), 2: (1, 2), 3: (2, 2), 4: (1, 1), 5: (1, 0), 6: (1, -1)}

# Labels to reflect parts of a neuron

labels = {

1: 'Dag',

2: 'Games',

3: 'Allegory',

4: 'Cooperative',

5: 'Iterative',

6: 'Adversarial'

}

# Draw the graph with neuron-like labels

nx.draw(G, pos, with_labels=True, labels=labels, node_size=5000, node_color='lightblue', arrows=True)

plt.title("Tension in Bow (Inherited & Added Constraints) +\n Release of Arrow (For Loftiest Goals)")

plt.show()

Fig. 34 DAG, Games, and Allegory. This figure is inspired by my training in epidemiology which would view a population (persons, places, times) as initially being “exposed” to something (cooperative games), setting in a cascade of processess “mediated” by downstream factors (iterative games), and ultimately resulting in some outcome (adversarial games). This Directed Acyclic Graph helps us describe games using similar place holders in terms of the role of information: cooperative (no information: just faith, hope, love, peace), iterative (update information, engage, subdue if “unworthy” adversary, and ascend to cooperative game… otherwise iterate with “worthy” adversaries), and adversarial (strategically asymmetric information with potential for cooperative equilibrium when resources of one adversary are exhausted). In simple terms, this DAG is about the descent from paradise to hell among those who break orbit, escapinig the gravitational pull of their mentor or lord. Among those for whom this merely represents “playing the prelude to the usual Romantic finale—break, collapse, return, and prostration before an ancient belief, before the old gods…”, like Dante, then a path of redemption from inferno -> limbo -> pradiso beckons.#