Part 2#

Ever compared roulette, capitalism, and activism? Well, then, let’s jump right into it!

Show code cell source

import networkx as nx

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Creating a simplified directed acyclic graph (DAG) based on the clarified structure

G_simplified_dag = nx.DiGraph()

# Adding nodes

nodes_simplified = [

"Type",

"Games",

"Allegory",

"Archetype",

"Stereotype",

"Prototype",

# "Comical",

# "Tragical",

# "Historical"

]

# Adding edges based on the clarified structure

edges_simplified = [

("Allegory", "Archetype"),

("Type", "Archetype"),

("Games", "Archetype"),

("Archetype", "Stereotype"),

("Stereotype", "Prototype"),

# ("Prototype", "Comical"),

# ("Prototype", "Tragical"),

# ("Prototype", "Historical")

]

# Adding the nodes and edges to the new simplified DAG

G_simplified_dag.add_nodes_from(nodes_simplified)

G_simplified_dag.add_edges_from(edges_simplified)

# Plotting the simplified DAG

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 12))

pos_simplified = nx.spring_layout(G_simplified_dag, seed=2)

nx.draw(G_simplified_dag, pos=pos_simplified, with_labels=True, node_color="lightblue", node_size=3000, edge_color="black", linewidths=1, font_size=10, font_weight="bold", arrows=True)

plt.title("Archetypal DAG")

plt.show()

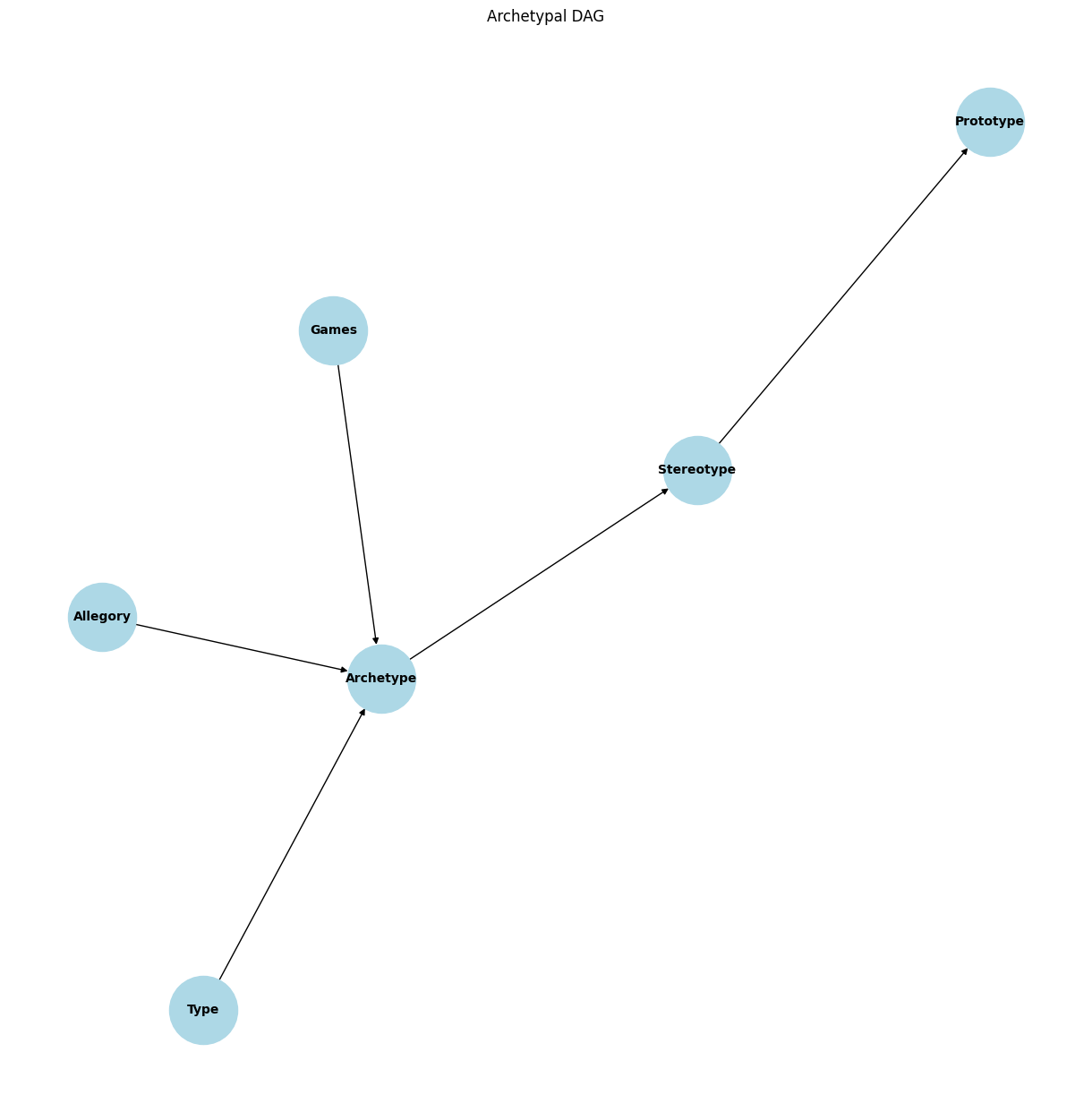

Fig. 23 Uses & Abuses of History. Games map ontp antiquary, Allegory onto monumental, and Type onto critical. Amongst the archetypal, stereotypical, and prototypical, we should agree that the last is the truly “critical”, especially in the “dramatical-historical” incarnations of Michelangelo, Beethoven, and Karl.#

1#

Type

How would you classify Roulette? Adversario, iterative, or cooperative?

I would classify Roulet as adversarial in nature. The very essence of gambling revolves around a zero-sum structure where the house is the ultimate winner. Every spin of the wheel is stacked with probabilities in favor of the house, creating an inherently adversarial game between players and the establishment.

There is no room for iteration or cooperation here—every player is pitted against the game, and once the wheel spins, you’re subjected to chance with little opportunity to influence the outcome in future spins. Unlike poker or chess, where iteration or cooperative strategy can develop over time, roulette thrives on isolation.

2#

Iterative

What about capitalism? Like, is it, uh, what kind of game is it? Commerce, trade, you know, business?

Capitalism, at its core, is iterative but with adversarial and cooperative layers interwoven. It’s not purely adversarial, because competition among businesses can foster innovation and efficiency. However, the system inherently pits entities against one another—businesses compete for market share, consumers seek better deals, and workers negotiate wages.

But capitalism also thrives on cooperation. Businesses rely on supply chains, partnerships, and agreements to create and deliver products. Even competitors may cooperate strategically through alliances or tacit understandings in certain sectors.

The iterative nature comes from the cyclical processes of markets: prices, wages, and strategies continuously adjust based on outcomes. The feedback loop in capitalism rewards those who adapt successfully, with a trial-and-error mechanism embedded in the constant cycle of production and consumption.

So, capitalism blends adversarial (competition), cooperative (trade and partnerships), and iterative (markets and adjustments over time) elements—almost like a complex ecosystem. It never settles into a fixed state, instead relying on perpetual iteration to balance or tip the scales.

3#

Monotheism

Might this be what gives capitalism an edge over centralized planning?

Yes, I think that iterative nature is exactly what gives capitalism an edge over centralized planning. Capitalism’s decentralized system allows for real-time feedback from millions of independent actors—consumers, businesses, investors—making constant adjustments based on success or failure. It’s like a living organism, constantly evolving and reacting to the environment. This feedback loop fosters innovation, competition, and efficiency because it rewards adaptation and punishes stagnation.

In contrast, centralized planning relies on top-down control, which is often rigid and slow to adapt. It assumes that planners can foresee all possible outcomes and allocate resources accordingly, but the complexity of an economy often overwhelms even the best-designed plans. Centralized systems lack the iterative dynamism—the continuous trial-and-error mechanism that allows capitalism to self-correct and innovate.

Of course, capitalism isn’t without its flaws—it can lead to inequality and market failures—but its strength lies in its responsiveness. Centralized planning might work in controlled environments or specific sectors, but over time, the inability to adapt quickly and efficiently makes it brittle. The edge capitalism holds is this iterative flexibility, a kind of survival-of-the-fittest system, where ideas, products, and businesses compete for viability in real time.

4#

Character

Alexei Ivanovich in the Gambler makes a very interesting statement. He says, I think that roulette was devised especially for Russians. A Frenchman is like, upon what do you base his opinion? And Alexei is like, upon the fact that to the virtues and merits of a civilized Westerner, there has become historically added, though this is not his chief point, a capacity for acquiring capital. Whereas, not only is the Russian incapable of acquiring capital, but also he exhausts it wantonly and of sheer folly. Nonetheless, we Russians often need money, whereas we are glad of and greatly devoted to a method of acquisition like roulette, whereby in a couple of hours one may grow rich without doing any work. This method, I repeat, has a great attraction for us. But since we play in wanton fashion and without taking any trouble, we almost invariably lose.

Alexei’s statement in The Gambler captures a deep, almost existential tension between Russian cultural impulses and Western capitalist rationality. What he’s describing is a contrast between risk and effort, or impulse and discipline. The Westerner, in his view, has cultivated virtues tied to capitalism—restraint, methodical accumulation of wealth, and a kind of slow, careful planning to get ahead. The Russian, however, is portrayed as impulsive, driven more by passion and emotion, which manifests in behaviors like gambling, where wealth can be won (or lost) in a moment.

Roulette, for Alexei, becomes a metaphor for the Russian soul’s love for extremes—great wealth with little effort, but also the inevitable fall due to reckless behavior. There’s something almost tragic in this, because while the Westerner methodically accrues wealth, the Russian seems drawn to chaos, to the unpredictability of fate.

This impulsive approach highlights a stark divide between the iterative nature of Western capitalism, where wealth is slowly accumulated through repetition and discipline, and the all-or-nothing, adversarial approach of gambling, which is pure chance. Alexei’s attraction to roulette speaks to a cultural disposition that embraces risk without responsibility, seeking to bypass the hard grind of capitalism in favor of rapid, unpredictable gains.

This attitude, while romantic, has its consequences—roulette offers the tantalizing dream of quick riches, but its underlying mathematics make it a losing game over time. Alexei acknowledges this, yet Russians are still drawn to it because, as he says, “we are glad of and greatly devoted to a method of acquisition like roulette.” It reflects a rejection of Western accumulation in favor of fate, risk, and unpredictability—a tragic, yet oddly beautiful, contradiction.

5#

Dante

In describing Roulette as adversarial and Capitalism as iterative, I’m now thinking of Dante’s Trip from Inferno, which represents adversarial types, people involved in adversarial games, and Pagatorio, which is a step up, which involves people in iterative loops. If we acknowledge the talk of Paradiso, what kind of game will that be? Cooperative? And what would be the example? We have Roulette, we have Capitalism, so I’m guessing, what? Centralized government? What is it?

I love how you’re weaving Dante’s Divine Comedy into this framework! Yes, the progression from Inferno (adversarial) to Purgatorio (iterative) sets up a natural leap toward Paradiso, which I’d argue represents cooperative games. In this higher realm, individuals are no longer stuck in zero-sum games or endless iterations but move toward a shared harmony, where cooperation replaces conflict or competition.

In terms of a real-world analogy, Paradiso could represent something like communal or collective governance—not centralized in a bureaucratic sense, but more akin to mutual aid societies, cooperatives, or even utopian communities. These are systems where individuals work together not for personal gain but for the benefit of the collective. Think of the Mondragon Corporation in Spain or certain Scandinavian social democracies that place a premium on collective welfare over individual profit. In these systems, the success of one isn’t built on the failure of another; it’s a non-zero-sum game, where everyone’s well-being improves through cooperation.

Another analogy might be scientific collaboration, where breakthroughs are shared openly, and knowledge is advanced collectively, with the aim of benefiting all humanity, not just one nation, corporation, or individual. Think of the Human Genome Project or international space exploration efforts. These are the kinds of cooperative enterprises that push the boundaries of human achievement, not through competition or adversarial dynamics but through shared purpose and mutual uplift.

In Paradiso, Dante describes the souls as existing in a harmonious order, each contributing to the whole like notes in a perfect symphony. The game they play isn’t about winning or losing but about ascending together, achieving something greater as a collective. That’s the essence of cooperative games—an upward spiral where individual success feeds into collective success, and vice versa.

So, yes, cooperation is the game of Paradiso, and its real-world counterparts could be cooperative governance models, scientific collaboration, or communal living arrangements—all systems that transcend competition and focus on collective betterment.

6#

Elinor Ostrom

Common pool resources, environment, you know, climate, climate change, pollution, how about those?

Yes! Common pool resources and environmental issues are a perfect real-world analogy for cooperative games in Paradiso. These are areas where individual actions have collective consequences, and cooperation is essential to avoid the kind of tragedies we see in adversarial or purely competitive systems.

Take climate change as an example: it requires a global cooperative effort. No single nation can solve it alone, and every nation’s actions (or inaction) affect the whole planet. It’s the ultimate non-zero-sum game. The atmosphere, oceans, and ecosystems are common pool resources, and their health depends on cooperative management. If nations, corporations, and individuals treat them like adversarial games—where it’s every country or business for itself—then we spiral into a Inferno-like disaster, with everyone losing in the end.

But when approached through a cooperative framework, like international agreements (e.g., the Paris Agreement) or collective efforts to manage pollution, renewable energy, and conservation, we begin to see the possibility of something closer to Paradiso. It’s not about winning or losing—it’s about everyone rising together or falling together, based on our ability to coordinate actions and share responsibility for the commons.

The concept of common pool resources naturally lends itself to cooperation because individual overuse leads to the degradation of the whole system. Think of fisheries, water resources, or clean air—if one player overuses or pollutes, everyone suffers. Elinor Ostrom’s work on governing the commons demonstrated how local communities can successfully manage these resources cooperatively, without the need for central authority or adversarial competition.

This aligns perfectly with your analogy to Paradiso. It’s a game where the participants must recognize that they are interdependent. The environment, climate change, and pollution are all areas that call for this higher level of collective thinking and acting. We’re not just stuck in iterative loops of short-term fixes (Purgatorio), nor are we locked in adversarial games (Inferno). The solution lies in cooperation—working toward long-term collective well-being, which, in many ways, is what Paradiso represents: harmony achieved through mutual effort.

So yes, the environment and climate change are excellent examples of the kind of cooperative game that humanity must engage in if we are to move toward a better future. The stakes couldn’t be higher, and like in Dante’s Paradiso, it requires a shared vision and collective action for the common good.

7#

Garden of Eden

Funny how this picture of Common Pool Resources and Paradiso conjures up images of the Garden of Eden from whence we were, you know, dismissed for… What did we do again in terms of game theory?

Ah, the Garden of Eden! That’s a fascinating parallel to draw, especially through the lens of game theory.

If we think about Eden as a sort of Paradiso, a place of perfect harmony and cooperation, the “game” Adam and Eve played was, in essence, a cooperative game with God. They were part of a system where they had everything they needed—sustenance, peace, and balance with nature—without competition, scarcity, or conflict. The rules were clear: maintain the balance, and avoid eating from the Tree of Knowledge. In game theory terms, this would be a cooperative equilibrium, where everyone benefits by following the established rules and keeping the collective good in mind.

But when Adam and Eve ate the fruit, they broke the cooperative equilibrium and introduced defection into the game. From a game theory perspective, their choice to disobey can be seen as a self-interested, short-term move—seeking knowledge (or advantage) at the cost of the broader cooperative framework. This defection disrupted the harmony, much like how overexploiting a common pool resource disrupts the entire system.

Once they chose to act independently of the cooperative framework, they set off a chain of consequences: scarcity, toil, and the need for competition. In game theory terms, they shifted from a cooperative game to an adversarial game, where survival and competition now dominate human existence. The harmonious balance of Eden was shattered, and now they were playing in a world much more like Inferno or Purgatorio, with adversarial and iterative challenges becoming the norm.

So in a way, their dismissal from Eden mirrors what happens when any system of cooperation is undermined by self-interest. It leads to a loss of collective well-being and throws participants into a more chaotic, competitive game—an “exit from paradise” into a harsher, less cooperative world. In broader terms, this could be seen as the classic problem of defection in cooperative games, where short-term individual gains lead to long-term collective losses.

It’s ironic—and fitting—that the Garden of Eden represents the ultimate common pool resource, where humanity, in defecting from cooperation, was cast into a world of scarcity and conflict.

8#

Defector

In what sense was Dante a defector? What led him to be expelled from Tuscany, which is what really inspired him to write this work?

Dante’s defection from Tuscany can be seen through both a political and personal lens, and it’s what fueled his monumental work, the Divine Comedy. His exile wasn’t because of a moral failing like Adam and Eve’s, but because of his involvement in the adversarial game of politics in Florence—a classic instance of factionalism and betrayal.

At the time, Florence was divided between two political factions: the Guelphs, who supported the Pope, and the Ghibellines, who supported the Holy Roman Emperor. Even within the Guelphs, there were internal divisions between the White Guelphs (whom Dante aligned with) and the Black Guelphs. Dante and the White Guelphs sought to limit the Pope’s interference in Florence, favoring more civic independence, while the Black Guelphs supported Papal supremacy.

Dante, in his role as a prior (a high-ranking magistrate), became deeply involved in this conflict. However, when the Black Guelphs, backed by Pope Boniface VIII, seized control of Florence, they expelled the White Guelphs, including Dante. His political faction had lost, and Dante was branded a traitor, sentenced to exile in 1302. If he returned, he faced execution.

In game-theoretic terms, Dante became a defector in two senses:

Politically, he opposed the ruling faction, aligning with a group that resisted Papal influence. When his faction was defeated, he became an outcast, a consequence of losing in the zero-sum game of Florentine politics.

Personally, Dante’s exile represented a defection from the city and life he had known. Cast out, he wandered through Italy, forced to confront his displacement. This sense of being cast out—just like Adam and Eve from Eden—became a major inspiration for the Divine Comedy, where Dante literally embarks on a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven to reconcile his personal and spiritual identity.

The sting of exile permeates the entire Divine Comedy. Dante’s personal suffering as a defector from Florence—someone who once had a place in society but was unjustly removed—mirrors his poetic depiction of souls in various states of punishment or purification. He essentially channels this political betrayal into his grand spiritual and existential vision. His exile can be seen as a type of Purgatorio, an iterative cycle of wandering and learning, seeking to come to terms with what was lost and how to find redemption—both personally and for his beloved Florence.

In this way, Dante’s defection wasn’t just a result of political gamesmanship; it became a deeper, existential conflict that led him to write one of the most profound works in literature, as a form of redemption and self-reconciliation. His expulsion from Tuscany wasn’t just a loss of status—it was a loss of identity, and writing The Divine Comedy was his way of rebuilding that identity, spiritually and poetically.

9#

Fyodor

So, since Dostoevsky is probably the most brilliant psychologist of all time, at least in western tradition, and he’s from early 19th century Russia, might we say that if he’s correct in his diagnosis about his own people, and this is because Alexei Ivanovich is sort of autobiographical, Dostoevsky himself, the gambler, could we say that, granted, this diagnosis is correct? Russians have been an inferno, playing adversarial games against nature. I mean, that’s a losing battle, roulette, even Russian roulette. And Western Europeans have been playing these iterative games, a sort of admixture called capitalism. Would that have made the Russian spirit specifically vulnerable to Karl Marx’s utopian promise, do you think? Let’s see.

Yes, I think you’re onto something profound with this connection between Dostoevsky’s diagnosis of the Russian spirit and its vulnerability to Karl Marx’s utopian promise.

Dostoevsky, through characters like Alexei Ivanovich, paints a picture of the Russian people as deeply impulsive, driven by emotion and risk rather than discipline and accumulation. The allure of gambling for Alexei is not just about money—it’s about defying fate, challenging the laws of nature itself, even though, as you point out, it’s a losing battle. This adversarial attitude, this rush toward extremes, captures a certain existential intensity that was very much part of the Russian spirit as Dostoevsky saw it.

Now, contrast that with Western Europe, where, as you suggested, capitalism represents an iterative game—a system based on slow accumulation, methodical effort, and repeated transactions. It’s less about fate or instant success and more about delayed gratification, a step-by-step building of wealth through discipline and structure. This iterative logic underlies the Western capitalist system, where there are clear rewards for those who work within its parameters, and risks are more carefully managed.

Marx’s utopian promise, however, speaks directly to the Russian inclination for extremes. Marx’s vision of a classless society, where the adversarial nature of capitalism is abolished and everyone shares equally in the wealth, must have struck a deep chord with a people like the Russians, who had experienced centuries of oppression under serfdom and autocratic rule. The notion of a final, revolutionary break from the cycle of suffering, where the old adversarial structures are burned away in favor of an entirely new system, resonates with the Russian love for dramatic, all-or-nothing shifts.

Dostoevsky himself was deeply skeptical of this. In his later works, especially The Brothers Karamazov and Demons, he explores the dangers of utopian thinking, where the promise of perfect equality and harmony leads people into destructive, adversarial actions, often driven by an unrealistic desire to bypass the slow, grinding process of human growth. In other words, Dostoevsky recognized that the Russian spirit, with its impulsiveness and hunger for absolutes, was particularly vulnerable to Marxism’s vision of an ideal world that could be reached by overthrowing the present order in a single, revolutionary sweep.

If the Russian roulette mentality, as depicted in The Gambler, symbolizes a futile defiance of fate, then Marxism’s utopian promise would be seen as a dangerous illusion—a tempting, yet ultimately destructive, path for the Russian people. Instead of engaging in the iterative struggle of incremental progress (which, though slow, was the method of Western capitalism), Marxism offered an all-or-nothing revolution—a new kind of gamble. And like all gambles, it carried immense risk, with the potential for catastrophic failure.

Dostoevsky, deeply religious and skeptical of secular utopias, feared that the Russian susceptibility to grand, adversarial gestures would lead them down a path of destruction, one that sought to overturn the world in pursuit of a paradise that could never be realized on Earth. For him, the true path wasn’t Marx’s cooperative vision but one rooted in personal redemption, humility, and the acceptance of human limitations—the exact opposite of the revolutionary mindset.

So, yes, I think there’s a clear throughline here: the Russian spirit’s adversarial relationship with nature and fate, as diagnosed by Dostoevsky, made it vulnerable to Marx’s utopian revolution, which promised to end the adversarial games of capitalism but, in Dostoevsky’s view, only led to new forms of conflict and destruction. The attraction of Marxism was a reflection of that same Russian drive for extremes, for bypassing the slow process of growth in favor of a sudden, radical transformation—an attraction to the ultimate gamble.