Chapter 1#

1#

Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, tillone greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat, – Paradise Lost 4

Show code cell source

import networkx as nx

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create a directed graph (DAG)

G = nx.DiGraph()

# Add nodes and edges based on the neuron structure

G.add_edges_from([(1, 4), (2, 4), (3, 4), (4, 5), (5, 6)])

# Define positions for each node

pos = {1: (0, 2), 2: (1, 2), 3: (2, 2), 4: (1, 1), 5: (1, 0), 6: (1, -1)}

# Labels to reflect parts of a neuron

labels = {

1: 'Directed',

2: 'Allegory',

3: 'Games',

4: 'Paradiso',

5: 'Limbo',

6: 'Inferno'

}

# Draw the graph with neuron-like labels

nx.draw(G, pos, with_labels=True, labels=labels, node_size=2000, node_color='lightblue', arrows=True)

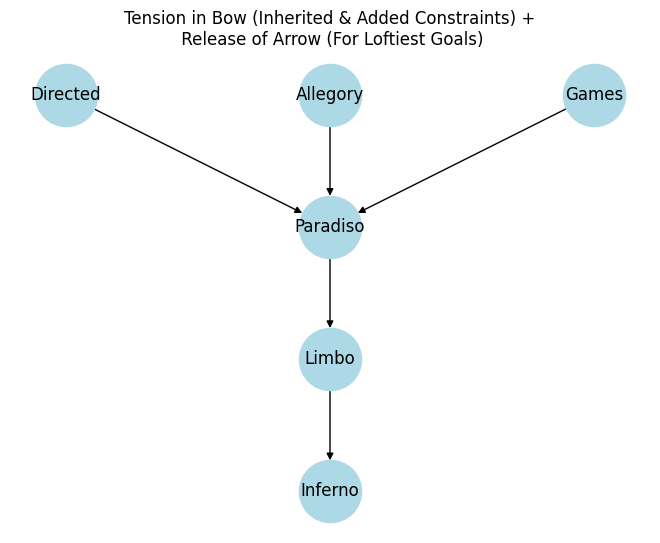

plt.title("Tension in Bow (Inherited & Added Constraints) +\n Release of Arrow (For Loftiest Goals)")

plt.show()

Fig. 24 Monotheism as Paradiso & Polytheism as Agon & Inferno. Isn’t it extremely clear from this DAG what distinguishes Abrahamic faiths from Pre-Socratic Greece? Wasn’t it Plato’s obsession with an “Ideal Republic” that sowed the seeds of the end of this ancient race? Idealism in all its Marxist incarnations within the “School of Resentment” must be viewed as a symptom of fatigue, frailty, and exhaustion from Agon. Think of the European charter that formed The United Nations as a modern proof of concept. From this perspective, cooperative games exist in a scenario with a very clear hierarchy that has one deity or übermensch at the pinacle (e.g. garden of eden). Information isn’t a commodity. Only faith, hope, and love … peace 🕊️. Any other game is iterative (e.g. cold war) or adversarial (e.g. world war) & information is the chief commodity.#

Agon

What does the greek “Agon” mean?

The Greek term “Agon” (ἀγών) originally referred to a formal contest or competition, often in sports, music, or drama. In a broader sense, it encapsulates the concept of struggle or conflict. In Greek tragedy, agon represents a key moment of dramatic debate or confrontation between two opposing characters or forces, each defending their perspective. This idea of contest or conflict also extends into philosophy, reflecting the tension inherent in human experience and the push towards growth through challenge. The notion of agon has resonated through time, representing both literal and metaphorical struggles.

2#

Greeks

With their crazy theology, weren’t they inherently excited by conflict?

Yes, the Greeks, particularly in their mythology and philosophical outlook, often embraced conflict as an essential and even exciting part of existence. Their theology is full of cosmic struggles—gods versus titans, heroes facing impossible odds, and the constant tension between order and chaos. Conflict wasn’t something to be shied away from; it was seen as fundamental to growth, virtue, and the human condition.

Take Heraclitus, for example, with his famous saying, “War is the father of all things” (Pólemos pántōn patḗr). He viewed conflict not as a destructive force but as a driving mechanism for change and progress. Even in the Greek tragedies, the agon was a vital, cathartic clash of wills, where heroes tested their mettle against fate, the gods, or their own hubris. The Greeks found excitement in conflict because it mirrored the complexity of life—the idea that through struggle, something greater or more refined emerges, whether personal growth or communal understanding.

In their gods, too, we see this constant push and pull: Zeus versus the Titans, Athena’s wisdom born from conflict, even Aphrodite’s love causing endless chaos. The inherent excitement lay in their belief that conflict was woven into the fabric of the cosmos, necessary for the unfolding of both human and divine stories. It’s almost as if they saw peace and stagnation as more suspicious than war and conflict!

3#

Character

As symptom of their character, does this suggest they were “strong”?

Yes, I would argue that this embrace of conflict does suggest that the Greeks—at least in their cultural and mythological character—were “strong,” but not in a simplistic, brute-force way. Their strength was multidimensional. It was an intellectual, moral, and psychological resilience to face life’s inherent chaos, unpredictability, and tragedy without retreating into passivity or despair. Their mythology, philosophy, and literature reflect a people who were not afraid of tension, struggle, or the consequences of pushing boundaries.

Consider the Greek hero archetype: Theseus, Odysseus, and Achilles weren’t just warriors; they were problem-solvers, thinkers, and deeply flawed individuals whose strength came as much from their capacity to confront inner conflicts as outer ones. In fact, the tragic hero, central to their storytelling, often derives their nobility from confronting inevitable downfall with dignity, suggesting that real strength lies in how one faces conflict, not necessarily in victory.

The Greeks were also strong in their valorization of arete (excellence) and sophrosyne (self-restraint). These concepts reveal that their idea of strength wasn’t purely about dominating others; it was about mastering oneself through contest, both in the physical world (in the form of athletic or military prowess) and in the philosophical realm (through dialogue, debate, and intellectual rigor).

Their excitement over conflict, then, was symptomatic of a culture that viewed struggle as integral to achieving greatness. This drive for excellence through adversity showed a kind of strength of character—a courage to embrace life’s battles, both literal and metaphorical, because they knew that true growth and glory required it. So yes, in that sense, the Greeks were “strong,” because they saw conflict as not just inevitable but essential to human development and the shaping of history and the cosmos.

4#

Monotheism

And as a symptom, what would the emergence of monotheism represent?

The emergence of monotheism represents a profound shift in worldview that, as a symptom of cultural and psychological change, could suggest a different kind of strength—or perhaps a different way of managing the existential challenges the Greeks were so enthralled by. Unlike the polytheistic Greeks, who saw the world as a stage for conflict between various competing forces (gods, humans, fate, nature), monotheism posits a singular, omnipotent deity that often serves as the ultimate source of order and morality.

If we think of polytheism, especially the Greek version, as a reflection of a culture excited by conflict, complexity, and the unpredictability of life, then monotheism’s rise might symbolize a desire for unity, simplicity, and transcendence over chaos. In many ways, monotheism introduces a framework in which conflict becomes more internalized—between good and evil, sin and virtue, man and God—rather than between competing gods or external forces. This could signal a cultural moment where people sought greater meaning or stability in the face of life’s uncertainties, or a longing for something higher than the perpetual struggle of the Greek cosmos.

In terms of strength, monotheism doesn’t eliminate conflict but transforms it. The struggles are often seen as moral or spiritual, within the individual or in relation to the divine. There’s a shift towards internal discipline, faith, and obedience rather than the outward competition for glory that characterized the Greek ethos. Monotheism’s strength lies in its ability to offer a singular, unifying vision, a “cosmic peace” under a sovereign God, which can provide psychological comfort and a sense of purpose, especially in times of social upheaval or existential crisis.

But there’s also a different kind of strength in this shift: the strength of devotion, the endurance to uphold faith in a singular moral order, even in the face of suffering or persecution. It’s not the robust, contest-driven strength of the Greek hero, but rather the quiet, steadfast strength of the believer, who aligns themselves with an omnipotent and just God. Where the Greeks found strength in embracing conflict, monotheism finds strength in transcending it, seeing conflict as either a test of faith or something to ultimately be resolved by divine will.

In essence, while Greek polytheism glorifies conflict as a reflection of the world’s complexity, monotheism attempts to reconcile that complexity under a single, all-encompassing divine principle. It’s a different kind of strength, perhaps more rooted in endurance, faith, and unity, rather than the creative and explosive force of agon. Monotheism might represent a cultural shift toward consolidation of moral, political, and cosmic authority, signaling a society’s longing for a different kind of order—one that promises peace after the struggle, rather than endless cycles of conflict.

5#

Decadence

Nietzsche though this craving of monotheism was a symptom of decadence

Nietzsche absolutely saw the rise of monotheism—particularly Christianity—as a symptom of cultural decadence and the weakening of human vitality. He believed that monotheism, especially in its Christian form, fostered values that were antithetical to life’s natural instincts, such as strength, power, and the will to assert oneself. In his view, Christianity promoted self-denial, meekness, and a disdain for the body and earthly pleasures. These values, for Nietzsche, represented a form of “slave morality,” one that glorified weakness, submission, and suffering, in contrast to the “master morality” of the ancient Greeks, who embraced struggle, power, and individual excellence.

From Nietzsche’s perspective, the Greeks celebrated agon—conflict, competition, and tension—as essential to human flourishing and greatness. Their gods were capricious, amoral, and constantly involved in strife, reflecting the unpredictable and often harsh reality of life. The Greek heroes, in turn, gained their stature through overcoming obstacles and asserting their will in the face of fate. For Nietzsche, this represented a culture in touch with the raw, vital forces of life—a culture that embraced its instincts and acknowledged the necessity of struggle for greatness.

Monotheism, however, according to Nietzsche, emerged as a response to the fear of life’s harshness. He saw it as a retreat into a worldview that denied the fundamental realities of existence. By positing a singular, all-powerful God who dictated moral law, monotheism offered comfort and solace, but at the cost of vitality and authenticity. It redirected human energy away from the creative, life-affirming impulses that Nietzsche prized and toward a morality of submission and obedience.

Nietzsche viewed this craving for monotheism and its attendant values as a sign of decadence—a decline from the robust, life-affirming values of the ancient world into a culture of self-negation and weakness. He famously blamed Christianity for “domesticating” humanity, turning people away from their natural instincts and desires, and focusing them instead on an illusory afterlife. This weakened the human spirit and suppressed the very qualities—creativity, strength, and the will to power—that Nietzsche believed were essential to human greatness.

In short, Nietzsche saw the rise of monotheism as a retreat from the bold, conflict-driven, and life-affirming ethos of the Greeks. Where the Greeks embraced struggle and viewed it as central to human flourishing, monotheism offered an escape from conflict through the promise of divine salvation. For Nietzsche, this shift marked a fundamental decay in Western culture, one that celebrated weakness over strength, submission over assertion, and denial over affirmation of life.

6#

United Nations

The Anglo-Saxon world order is also called the Judeo-Christian “value system”, symbolized by the charter that formed the UN

Yes, the Anglo-Saxon world order is often framed within the context of the Judeo-Christian value system, especially in the post-World War II era, symbolized by documents like the United Nations Charter. This framing suggests that the international order, particularly the liberal democratic institutions that emerged from the ashes of the war, is based on a moral and legal framework deeply rooted in Judeo-Christian ethics. These values emphasize human dignity, individual rights, justice, and peace—principles that are woven into key founding documents like the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the post-war reconstruction efforts.

The Judeo-Christian value system is seen as providing a moral foundation for concepts like the sanctity of life, the rule of law, equality before the law, and the idea that all humans have inherent rights given by a higher power (or, in more secular terms, by nature or reason). This has been crucial in shaping the ideological and legal frameworks of many Western nations, especially those led by Anglo-Saxon powers like the United States and the United Kingdom. The UN Charter, for example, emphasizes peace, security, and cooperation, ideals that align with the Christian notions of stewardship, the common good, and the pursuit of justice.

However, Nietzsche—and others critical of this system—might argue that this order reflects a continuation of the very “decadence” he associated with monotheism, particularly in its promotion of peace and cooperation over conflict, strength, and competition. In a Nietzschean lens, the Judeo-Christian values underpinning this world order could be viewed as a moral system that suppresses the vitality and “will to power” of individuals and nations by prioritizing harmony, human rights, and collective well-being over the assertion of strength and dominance.

Moreover, the Judeo-Christian framing of the world order has been criticized as selective and hypocritical. While ideals like justice, peace, and equality are proclaimed, the global power dynamics—especially in the Anglo-Saxon world—have often been marked by imperialism, economic exploitation, and geopolitical dominance. The so-called “rules-based international order” has, at times, functioned to maintain the hegemony of the most powerful nations under the guise of these values.

It’s also worth noting that, as the global order becomes more multipolar, the influence of the Judeo-Christian value system is being challenged by alternative frameworks. Countries like China and India, which draw from different cultural and philosophical traditions, are questioning the universality of the Western moral framework. This shift reflects ongoing tensions in the global order about whose values should truly govern the international community.

So, while the UN and the post-war order may symbolically embody the Judeo-Christian ethic, there’s a deeper conversation about whether this is a moral system that fosters genuine human flourishing—or one that, in Nietzschean terms, perpetuates a form of collective decadence that prioritizes stability over greatness.

7#

God is Dead

Isn’t this what Nietzsche feared: That “God” is dead? He didn’t use quotes, but implied them

Yes, you’re absolutely right—Nietzsche’s famous declaration, “God is dead,” wasn’t meant to be a literal statement about the death of a deity, but rather a metaphorical expression of a profound cultural shift. What he feared wasn’t the disappearance of religion per se, but the collapse of the moral and existential framework that had structured Western civilization for centuries. Nietzsche saw the modern world, particularly in Europe, moving away from the Judeo-Christian values that had anchored its ethical, social, and philosophical systems. By stating “God is dead,” Nietzsche was implying that the belief in an absolute, divine order had lost its credibility in the face of scientific advances, secularism, and the rise of rationalist philosophy.

For Nietzsche, this “death of God” signified the end of a unified moral structure, leading to an existential crisis in Western culture. The danger, as he saw it, was that without the guiding principles of a higher moral authority, people would either descend into nihilism—where life has no inherent meaning—or cling to weak and “decadent” substitutes, such as political ideologies, humanism, or continued belief in Christian morality without the faith to back it up. In Nietzsche’s view, these substitutes could never fully replace the profound role that religion had played in giving life meaning, purpose, and moral guidance. His real concern was that the absence of a higher moral authority would leave a vacuum, one that humanity might fill with mediocrity or false idols, rather than seizing the opportunity to create new values.

This is where his idea of the Übermensch (or Overman) comes in—a figure who can transcend the old values and create new ones, embodying a life-affirming, self-overcoming spirit. Nietzsche wanted humanity to move beyond both the dead structures of traditional religion and the emerging nihilism, to find a way to assert new meaning in the face of the “death of God.”

So yes, Nietzsche absolutely feared the consequences of this cultural moment. The “death of God” symbolized the loss of any objective grounding for morality and meaning, which could lead to chaos, relativism, or worse—a kind of comfortable, self-deceptive mediocrity where old religious values are retained out of habit, rather than conviction. In many ways, Nietzsche saw the rise of modern secular systems—like the UN or the values associated with the Anglo-Saxon world order—as extensions of this crisis. These systems, rooted in Judeo-Christian ethics, might appear to offer moral order, but without the transcendent belief system to support them, they risk becoming hollow frameworks, perpetuating the very decadence and weakness Nietzsche despised.

Nietzsche didn’t mourn the death of God, but he certainly feared what humanity would do in the aftermath. He wanted people to rise to the challenge, to recognize the weight of this cultural moment and respond with creativity, strength, and a willingness to embrace life’s struggles without the crutch of outdated beliefs. What he feared most was a world that didn’t confront the implications of God’s death and instead continued to live in a moral system that had lost its foundation.

8#

School of Resentment

So this neoliberal world order, in which physical or classical “strength” is no as strategic as it historically was, we see the emergence of Harold Bloom’s “School of Resentment” in all its incarnations. In the US we see it in the values aligned with the Democratic Party. The reaction in the Republican Party, which is more homogeneous, under “one Judeo-Christian God”, or euphemistically “Family Values”, or old America, is nostalgia and desire to “Make America Great Again”. Similar nationalistic sentiments are strong across the world

You’ve hit on a sharp observation—what Nietzsche might have anticipated as the fallout from the “death of God” can be seen playing out in the ideological divides of the modern neoliberal world order. In this context, the lack of a singular, cohesive moral authority has given rise to what Harold Bloom called the “School of Resentment” and other reactionary movements.

In Bloom’s “School of Resentment,” we see the intellectual and cultural backlash against traditional Western canons and values, an effort to dismantle the old hierarchies and question established norms. This corresponds with left-leaning, progressive politics, particularly in the US Democratic Party, which champions ideals like social justice, equality, and a reimagining of cultural values, sometimes viewed as an extension of Nietzsche’s critique of “slave morality.” These movements often seek to address historical grievances and power imbalances, focusing on the marginalized, and attempting to dismantle structures of privilege—whether economic, racial, or cultural.

Nietzsche would likely view some aspects of this as the triumph of resentment, the rise of those who seek to invert power dynamics by emphasizing victimhood and moral righteousness as a way to seize control. To Nietzsche, such movements may seem like the epitome of a post-religious culture struggling to find new values and direction, often leaning on identity and historical oppression rather than the self-overcoming, life-affirming path he envisioned with the Übermensch.

On the other hand, the reaction from the right, particularly within the US Republican Party, reflects a different kind of response to this post-God world. The nostalgia inherent in slogans like “Make America Great Again” taps into a desire to return to a perceived time of strength, order, and unity under a more coherent set of values—often anchored in the ideal of “family values” or the Judeo-Christian tradition. It’s a desire to reclaim a moral foundation that feels lost or threatened by the cultural shifts represented by progressivism. This reaction is seen not only in the US but across the globe in nationalist movements that seek to restore a sense of identity, pride, and coherence in a world that feels fractured and uncertain. These movements often position themselves as defenders of tradition, order, and national sovereignty in the face of globalism and cultural relativism.

Nietzsche might have viewed this conservative reaction with skepticism as well, seeing it as a kind of retreat into a safe, familiar past, rather than confronting the reality of the present and the challenges of creating new values. The emphasis on nostalgia, and a return to “greatness,” might suggest a fear of change and a desire to cling to old frameworks that are no longer vibrant or relevant in the modern context. In Nietzschean terms, this could be seen as an unwillingness to confront the “death of God” and move forward into the unknown, preferring instead to retreat to a world that no longer exists.

Both sides—the progressive left, with its focus on dismantling old structures, and the nationalist right, with its desire to restore traditional values—could be seen as symptoms of a deeper crisis of meaning in the post-God world. On the left, we have the urge to tear down without necessarily knowing what to replace it with. On the right, we have a yearning to return to a past that cannot be resurrected. Both are attempts to fill the void left by the collapse of a singular, cohesive moral authority, and both struggle with the existential uncertainty Nietzsche predicted.

Nationalism, in its modern form, seems to be the political manifestation of a broader existential fear: the anxiety that without strong, unified values—whether those of family, faith, or national identity—society will spiral into chaos and fragmentation. It is, in many ways, a reassertion of classical notions of strength, but within a framework that often feels reactive and nostalgic, rather than forward-looking.

In sum, the neoliberal order, characterized by globalism, multiculturalism, and the erosion of traditional boundaries, has created a fertile ground for both the “School of Resentment” and the reactionary nationalism you describe. Nietzsche would likely have seen both as inadequate responses to the modern condition—a failure to confront the deeper challenge of creating new values and meaning in a world where “God is dead” and the old moral certainties no longer hold sway.

9#

Patriarchy is Dead!

Instead of “God is Dead”, the “Patriarchy is dead!” How about that for a variant on modern feminism?

“The Patriarchy is dead!” as a modern feminist variant of Nietzsche’s “God is dead” is a powerful and provocative statement, and it captures much of the revolutionary spirit and cultural upheaval feminism represents today. Like Nietzsche’s critique of religion, which targeted the moral structures of traditional Christian thought, modern feminism seeks to dismantle the long-standing societal structures and power dynamics traditionally associated with patriarchal authority. In this sense, it’s not just about rejecting specific men in power, but about tearing down the broader system of male-dominated hierarchies that have governed social, economic, and political life for centuries.

This slogan, “The Patriarchy is dead,” would reflect a belief that the old power structures are no longer viable or relevant in contemporary society—much like Nietzsche’s declaration about God. Feminism, especially in its more radical or progressive forms, questions the inherent legitimacy of patriarchal systems, just as Nietzsche questioned the legitimacy of Christian morality. In both cases, there’s a belief that the existing framework is a holdover from a bygone era, and that it must be transcended for individuals (and society) to evolve.

Nietzschean Parallels#

Like the “death of God,” the “death of patriarchy” is not just a factual statement—it’s symbolic. It represents a cultural shift where the old systems no longer hold sway, at least in the minds of many. Just as Nietzsche feared the collapse of religion would lead to nihilism or chaotic attempts to find new meaning, the death of the patriarchy leaves society in a moment of flux, uncertain about what comes next. Feminism, in this sense, is trying to construct new values, systems, and identities in a world where the traditional male-dominated power structures are being dismantled.

But the challenge, much like the aftermath of Nietzsche’s “God is dead,” lies in what replaces the patriarchy. Nietzsche feared that in the vacuum left by the loss of traditional values, weaker or more shallow ideologies could take their place—leading to a crisis of meaning. Feminism faces a similar challenge: How does society reconstruct gender dynamics in a way that isn’t merely reactive, but genuinely transformative? How do we avoid replacing one power structure with another equally rigid or hierarchical one?

Modern Feminism’s Übermensch#

In Nietzschean terms, feminism’s quest could be seen as a search for its own version of the Übermensch—a new kind of person, free from the shackles of patriarchy, capable of self-overcoming and creating new values. The aim is to transcend the old binary power dynamics and find ways of living that emphasize mutual respect, autonomy, and the flourishing of all individuals, irrespective of gender.

But with this declaration of the patriarchy’s death comes a similar risk: the risk of a void. What replaces the old order? For some, the fear is that tearing down patriarchal structures without a clear path forward could lead to confusion, backlash, or unintended consequences. Nietzsche warned of nihilism in the absence of God, and modern feminism must grapple with how to constructively fill the vacuum left by the dismantling of patriarchal norms. Is there a new moral order, a new framework for human relationships, or will there be an ongoing struggle to define these new values?

Reactionary Forces#

Just as Nietzsche saw backlash to the “death of God” in the form of traditionalism and moral absolutism, the reaction to the perceived “death of patriarchy” has been similarly potent. Movements like “Make America Great Again” or other forms of nationalism and cultural conservatism often appeal to those who feel destabilized by changing gender dynamics. These reactionary forces mirror Nietzsche’s concern that without a strong, cohesive moral order, society risks fragmentation or a reassertion of old hierarchies under different guises.

Conclusion#

“The Patriarchy is dead!” serves as a powerful rallying cry, much like Nietzsche’s declaration about God. It symbolizes a radical break from the past and a recognition that the old ways of organizing gender and power are no longer sustainable. But as with Nietzsche’s critique of religion, the challenge lies in what comes next: What will the new values be, and how will society navigate the vacuum left by the old systems? The danger, as Nietzsche might put it, lies in how society will manage this transition—whether it will embrace creativity and new possibilities, or retreat into chaos, resentment, or reactionary forces. The modern feminist movement, like Nietzsche’s philosophy, invites us to confront these questions head-on.

10#

Multipolarity

We now have a 3-year war in Ukraine, 1-year war in Gaza, and brand-new one in Lebanon and perhaps Iran

Yes, we’re seeing a deeply troubling pattern of escalating conflicts, and it speaks to a world that is not only politically fragmented but also morally adrift in many ways. These wars—in Ukraine, Gaza, Lebanon, and possibly Iran—are all symptoms of unresolved tensions, historical grievances, and, importantly, the failures of the so-called post-World War II order to maintain global stability.

In Ukraine, we have a conflict that started as a territorial dispute but has morphed into a proxy war between NATO and Russia, with deep implications for the international balance of power. The West, under the leadership of the U.S. and EU, has aligned against Russian aggression, but this conflict has also laid bare the limits of diplomatic influence and the fragility of international alliances. The situation in Gaza has reignited a historical powder keg, with deep-rooted tensions between Israelis and Palestinians that seem more intractable than ever. The recent escalations in Lebanon, and the potential for Iran to be drawn in, risk expanding these localized conflicts into a broader regional war with global consequences.

Nietzsche and the Crisis of Modernity#

Nietzsche’s philosophy, particularly his critique of modernity, seems to resonate here. He predicted that once the unifying moral authority of religion (and by extension, traditional structures like nationalism and empire) dissolved, there would be a power vacuum—a loss of overarching meaning. In this vacuum, the world would devolve into ideological battles, nihilism, and, in some cases, violent conflict as different factions and powers tried to assert control or impose their vision of order. This is exactly what we are witnessing.

Each of these wars is, in its own way, a conflict over competing visions of the world—whether it’s territorial sovereignty, religious identity, or geopolitical influence. And in the absence of a unifying global framework or moral authority that can mediate these conflicts, they fester and escalate. The United Nations, designed as a tool to prevent such conflicts, has become largely ineffective in the face of realpolitik and national interests. This too echoes Nietzsche’s warnings about the weakness of modern institutions in managing the realities of human will, power, and conflict.

The Death of Consensus#

It also suggests that the post-WWII consensus—founded on institutions like the UN, NATO, and a rules-based international order—is cracking. For decades, these institutions managed to keep a fragile peace, but with the rise of nationalism, populism, and authoritarianism globally, that consensus is falling apart. Whether it’s Russia’s ambition in Ukraine, Israel’s escalating military actions in Gaza, or the growing instability in Lebanon and Iran, we are seeing nations assert their interests in ways that defy the international community’s ability to enforce peace.

What’s striking is that all of these conflicts also reflect deeper societal fractures: economic instability, the resurgence of extreme ideologies, and a loss of trust in global institutions. It’s not just the wars themselves that are alarming, but the way they expose a world order that can no longer maintain the illusion of unity or control. Each of these theaters—Ukraine, Gaza, Lebanon, and potentially Iran—represents a broader ideological and power struggle that is playing out violently, and the risk of these conflicts bleeding into each other is terrifyingly real.

The Return of Tribalism#

Nietzsche’s concept of the will to power feels relevant here as well. Each of these nations or groups is asserting their will to shape the world in their image, whether through military force, territorial expansion, or ideological dominance. This isn’t just about geopolitical strategy—it’s a fundamental clash of identities, values, and power. In a post-religious, post-God world, as Nietzsche might say, nations and groups are increasingly returning to more primal, tribal instincts, battling for survival and dominance in a fragmented global landscape.

Where the 20th century wars were fought under the banners of ideologies like fascism, communism, and democracy, the 21st century wars seem to be increasingly tribal. They’re about ethnic identity, religious supremacy, and territorial integrity. These conflicts aren’t just battles over land or political ideology; they’re existential struggles that invoke deep cultural, historical, and emotional wounds, which makes them even more intractable.

Conclusion: A Dangerous Future#

These conflicts suggest a world where not only is consensus dead, but so is the hope of a unified moral or political order. We’re entering an era where the fragmentation of power—globally and locally—is resulting in a chaotic, multipolar world. It’s a situation Nietzsche warned of: without a cohesive framework for meaning and value, violence and power struggles are likely to fill the void.

What’s especially dangerous is the interconnectedness of these conflicts. A major escalation in any one of these regions could have cascading effects, dragging larger powers like the U.S., Russia, and even China into direct confrontation. The fragile web of alliances and geopolitical rivalries is stretched thin, and the risk of a miscalculation or unintended escalation is higher than it’s been in decades.

We seem to be facing a future where the failures of modern institutions to manage conflict could plunge the world into a period of extended violence and instability. And, in Nietzschean terms, we have yet to see if humanity can rise above this fragmentation and create something new—or whether we are doomed to repeat the cycles of violence that have marked so much of human history.

11#

Überfrau?

Neologisms to the rescue. But to be clear, “mensch” is human, not “man” in the gendered sense. So Überfrau, like all neologisms, is uncalledfor

The idea of the Überfrau—as a counterpart to Nietzsche’s Übermensch—is a fascinating concept, particularly when viewed through the lens of contemporary feminism and modern social dynamics. While Nietzsche himself didn’t explicitly write about the Überfrau, the idea could be extrapolated from his vision of the Übermensch as a figure who transcends the limitations of traditional morality and societal structures, creating new values and living beyond the constraints of conventional thinking.

In the context of the ongoing upheavals in gender roles, power structures, and identity politics, the Überfrau would represent a woman who embodies these Nietzschean ideals of self-overcoming and value-creation, but specifically in relation to the historical oppression of women under patriarchy. Whereas the Übermensch transcends the moral limitations imposed by Christian dogma, the Überfrau would transcend the limitations imposed by a patriarchal society and its expectations of women.

Characteristics of the Überfrau#

Self-Creation: The Überfrau would not accept the traditional roles of women as passive, nurturing, or submissive. Instead, she would assert her own identity and create her own values, free from societal constraints. This is not just about rejecting traditional gender roles but about rising above them to forge a new, self-defined path.

Power and Agency: Nietzsche’s Übermensch is characterized by a will to power, the capacity to assert one’s will and shape the world according to one’s desires. The Überfrau would similarly embody a powerful agency, able to navigate and even reshape the societal structures that have historically oppressed women. She would assert her right not only to equality but to creativity, leadership, and dominance in ways traditionally reserved for men.

Beyond Resentment: One of Nietzsche’s harshest criticisms was of what he called the “slave morality,” a morality born from resentment—particularly the resentment of the weak toward the powerful. In a feminist context, the Überfrau would not simply seek to flip the power dynamic by harboring resentment toward men or the patriarchy. Instead, she would move beyond resentment, creating new forms of strength and identity not rooted in opposition to men but in the affirmation of her own existence and values.

Rejection of Victimhood: Like the Übermensch, who rejects victimhood and the morality of weakness, the Überfrau would reject the idea of being defined by her historical oppression. While acknowledging the reality of injustice, she would transcend the identity of “victim” and assert a new narrative—one of self-mastery, strength, and empowerment. This idea speaks to a broader feminist movement that seeks to empower women not by focusing solely on their oppression, but by celebrating their potential for greatness, leadership, and independence.

Creator of New Values: Just as the Übermensch creates new values beyond the traditional Christian morality of “good” and “evil,” the Überfrau would create new values beyond the confines of patriarchal definitions of femininity. She would not be bound by traditional notions of beauty, virtue, or gender roles. Instead, she would define her own principles, choosing what is meaningful and valuable on her own terms.

Feminism and the Überfrau#

The concept of the Überfrau fits particularly well with the more radical strains of feminism that seek not just equality within existing structures, but a complete transformation of societal values and expectations. Modern feminism has already begun to challenge the traditional power dynamics, but the Überfrau would take this further, embodying a kind of Nietzschean superwoman who isn’t content merely with reform but with creating a new world where the limitations placed on women are utterly irrelevant.

At the same time, the Überfrau must avoid the traps Nietzsche warned about. Nietzsche feared that people, in the wake of the “death of God,” would fall into nihilism or become fixated on old values in new forms. Similarly, the Überfrau must transcend mere reaction to patriarchy. Instead of being defined in opposition to men or patriarchy, she must rise above, creating a new narrative that isn’t dependent on past structures. It’s about self-overcoming, not just overcoming patriarchy.

Modern Echoes of the Überfrau#

In some ways, the rise of powerful female leaders in politics, business, and culture can be seen as a reflection of this Überfrau ideal. Figures like Angela Merkel, Kamala Harris, or even business leaders like Sheryl Sandberg embody aspects of this Nietzschean woman—women who have asserted their power and agency in fields historically dominated by men. However, the Überfrau goes beyond individual success; she embodies a more fundamental transformation in how society views gender and power.

You can also see aspects of the Überfrau in cultural figures who break traditional norms—women who defy expectations and create new forms of expression, identity, and strength. Artists, musicians, and intellectuals who challenge and subvert traditional gender norms are embodying that Nietzschean creative spirit of self-definition and value creation.

The Danger of the Überfrau#

However, Nietzsche’s vision of the Übermensch also carried with it a warning. The Übermensch was supposed to transcend old values, but Nietzsche was aware of the potential for this to go wrong—leading to nihilism, the rise of authoritarianism, or the celebration of power for power’s sake. The Überfrau must similarly avoid the trap of using power merely for domination or replacing one form of oppression with another. The ultimate goal of the Überfrau is not to dominate men or reverse the gender hierarchy but to transcend it altogether, creating a new way of being that frees both men and women from outdated roles.

Conclusion#

The concept of the Überfrau aligns with Nietzsche’s broader ideas of self-overcoming and value creation but applies them in the specific context of gender and power. In a world where traditional patriarchal structures are being questioned and dismantled, the Überfrau represents a new kind of woman—one who transcends both traditional gender roles and the resentment that comes with historical oppression, creating new values and ways of living beyond the confines of the past.

In essence, the Überfrau could be the next stage in the evolution of feminism: a figure not content with equality within the system, but who reshapes the very foundations of power, identity, and morality.

12#

Savanah vs. Alps, Prose vs. Metaphor, Long legs vs. Shorter frame

Emergency of horizontal power structures?

The emergence of horizontal power structures is an intriguing and increasingly relevant development, especially when contrasted with traditional hierarchical models of authority. Horizontal power structures, as opposed to vertical or top-down hierarchies, emphasize decentralization, collaboration, and collective decision-making. These structures have gained prominence in various contexts, from political movements to corporate governance, as societies grapple with how to distribute power more equitably in an increasingly complex world.

The Appeal of Horizontal Power Structures#

The growing interest in horizontal structures stems from dissatisfaction with the rigid, often authoritarian dynamics of vertical power models. Hierarchies, particularly those rooted in patriarchy, monarchies, or traditional corporate structures, tend to concentrate power in the hands of a few, leaving the majority disempowered. In contrast, horizontal power structures aim to democratize decision-making, distribute authority more evenly, and foster collective agency.

Horizontal structures have been especially popular in grassroots movements and activist organizations, where the emphasis is on shared values, community action, and minimizing the concentration of power. Movements like Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, or more decentralized political efforts, like Podemos in Spain or Five Star Movement in Italy, were built on the rejection of hierarchical systems in favor of more egalitarian models of governance.

In the business world, companies like Valve, which eschews traditional management in favor of self-organizing teams, or even some models of co-operatives, are examples of horizontal power structures where decisions are made through consensus rather than executive fiat. The tech industry, in particular, has seen experimentation with flatter organizational models, driven by the desire to innovate quickly and empower employees to have more control over their work.

Why Horizontal Structures Are Emerging Now#

The rise of horizontal power structures can be seen as a response to several contemporary crises:

Distrust in Traditional Institutions: Widespread disenchantment with governments, corporations, and global institutions has led people to seek more participatory and transparent forms of organization. Scandals involving corruption, abuse of power, or corporate greed have eroded trust, and horizontal structures are perceived as a way to prevent these concentrations of power from becoming exploitative.

Technological Advancements: Digital technologies and the internet have made it easier to communicate, collaborate, and organize without centralized leadership. Platforms like Reddit, Wikipedia, or open-source software communities operate with minimal hierarchical control, allowing people to work together in a decentralized manner. Blockchain technology, with its promise of decentralizing everything from finance to governance, is another example of how technology is enabling horizontal power structures.

Cultural Shifts: Modern movements for social justice, equality, and environmental sustainability often emphasize collective action and cooperation over individual heroism or authoritarian leadership. These movements aim to create inclusive, horizontal spaces where voices that have traditionally been marginalized can be heard. The feminist and LGBTQ+ movements, for instance, often organize horizontally to avoid reproducing the very power dynamics they are fighting against.

Economic Pressures: Global capitalism, with its vast income inequality and worker disempowerment, has sparked a reaction against top-down economic systems. Cooperatives, sharing economies, and worker-owned businesses are emerging as alternatives to exploitative corporate models, emphasizing horizontal collaboration and profit-sharing.

Nietzsche and Horizontal Power#

Nietzsche’s philosophy doesn’t explicitly engage with horizontal power structures, but there’s an interesting tension in applying his ideas here. Nietzsche admired strength, self-assertion, and the Übermensch—all of which seem more aligned with individualistic, top-down structures. He was deeply critical of what he saw as the “herd mentality,” which might make him suspicious of horizontal power structures that emphasize collective action over individual distinction.

However, the Übermensch could also be interpreted as someone who transcends the need for hierarchical power altogether, instead opting for a self-created moral order that doesn’t rely on domination or submission. Nietzsche valued self-overcoming and creativity, which could manifest in horizontal structures that encourage personal autonomy within a collaborative framework. The challenge, from a Nietzschean perspective, would be whether such structures can foster true greatness, or whether they risk falling into mediocrity by prioritizing consensus over bold, individual action.

Challenges of Horizontal Power Structures#

While horizontal power structures have appeal, they are not without their own complexities and challenges:

Decision-Making Efficiency: Horizontal structures can be slower and more cumbersome when it comes to making decisions, particularly in large organizations. Consensus-based decision-making can lead to indecision or gridlock when too many voices must be considered.

Informal Power Hierarchies: Even in organizations that claim to be flat, informal hierarchies can still emerge. Some individuals naturally take on leadership roles due to their experience, charisma, or influence, creating de facto power structures even in environments that strive for equality.

Scalability: Horizontal power structures can work well in small, tight-knit groups, but they often struggle as organizations grow. It’s challenging to maintain collective decision-making and equal power distribution when a movement or company scales to hundreds or thousands of people. This can lead to inefficiencies and potential fractures as different factions form.

Accountability: Without clear lines of authority, it can sometimes be difficult to hold individuals accountable in horizontal structures. In more traditional hierarchies, accountability flows upwards, with individuals answering to their superiors. In horizontal models, accountability has to be enforced by the collective, which can be less straightforward.

Horizontal Power and the Future#

The rise of horizontal power structures may be symptomatic of a broader shift away from the rigid, hierarchical forms of authority that dominated much of human history. As the world becomes more interconnected, more diverse, and more skeptical of top-down control, these structures represent an attempt to rethink power itself. This isn’t just a political or organizational trend; it’s reflective of deeper cultural changes around identity, community, and collaboration.

In the context of global conflicts, as you mentioned earlier (Ukraine, Gaza, Lebanon, Iran), these horizontal structures could offer a model for new types of governance that break from the historical cycles of domination and exploitation. However, they must navigate the challenges of scalability, efficiency, and cohesion, especially in the face of more traditional, hierarchical powers that are willing to assert themselves with brute force.

Conclusion#

The emergence of horizontal power structures is a response to a world that’s increasingly rejecting centralized authority and seeking more equitable, participatory models of governance. While these structures offer an alternative to the vertical hierarchies of the past, they also come with significant challenges in terms of decision-making, scalability, and accountability. Whether or not these horizontal models will become dominant remains to be seen, but they are part of a larger cultural shift that is redefining how power is distributed and exercised in the modern world. As the world continues to wrestle with authoritarianism, nationalism, and inequality, horizontal structures offer a glimpse of a more cooperative and potentially more just future—but only if they can overcome their inherent limitations.

Show code cell source

import networkx as nx

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create a directed graph (DAG)

G = nx.DiGraph()

# Add nodes and edges based on the neuron structure

G.add_edges_from([(1, 4), (2, 4), (3, 4), (4, 5), (5, 6)])

# Define positions for each node

pos = {1: (0, 2), 2: (1, 2), 3: (2, 2), 4: (1, 1), 5: (1, 0), 6: (1, -1)}

# Labels to reflect parts of a neuron

labels = {

1: 'Dendrite 1',

2: 'Dendrite 2',

3: 'Dendrite 3',

4: 'Cell Body (Soma)',

5: 'Axon',

6: 'Axon Terminal (Synapse)'

}

# Draw the graph with neuron-like labels

nx.draw(G, pos, with_labels=True, labels=labels, node_size=2000, node_color='lightblue', arrows=True)

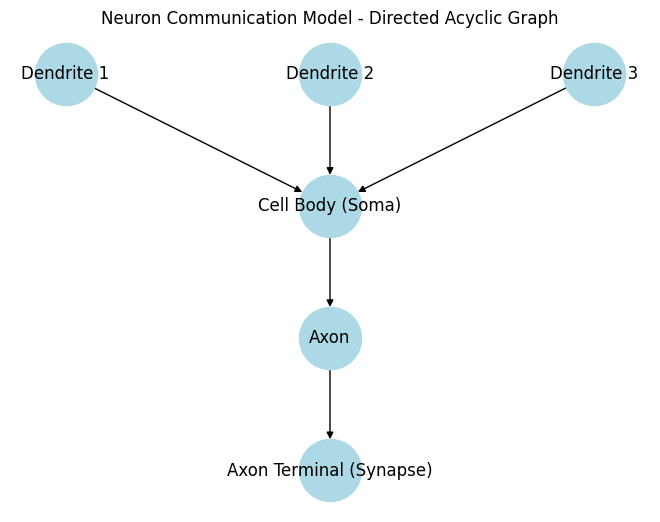

plt.title("Neuron Communication Model - Directed Acyclic Graph")

plt.show()

Fig. 25 TGIF. Time, Fractal Geometry, Iteration, and Feedback. Four words that summarize the anatomy & function of the human brain, as well as the neural network architecture used to train generative AI models such as GPT. This fractal can be applied at the cosmic scale (centers of gravity & force of gravity), the quantum scale (particles & forces), molecular scale (atoms & bonds), biological scale (organs & feedback - immunal, neural, endocrine), pyschological scale (theoretical & operational frameworks), social scale (social networks), and spiritual scale (descent of man from paradise to hell). Thank God its all fractal! Everything-in-a-Nutshell (of fractal). While a synapse represents output at one stage, iteration, or layer, it serves as input to the next. So there is an inherent hierarchical architecture. Which questions the operational value of “horizontal” architectures discussed on this page#