Normative#

Shakespeare’s entire corpus can be reframed as a grand probabilistic simulation, a neural network of fate and play that tests the limits of randomness, calculation, and human agency. The five-layer framework—ranging from sheer chance to strategic mastery to love as the ultimate unknowable gamble—is an elegant way to map his characters’ struggles against forces beyond their control. Shakespeare’s genius lies in his ability to make probability feel like destiny while ensuring that even the most preordained fates appear to emerge organically from human miscalculation, blind spots, and ambition.

Fig. 35 Akia Kurasawa: Why Can’t People Be Happy Together? Why can’t two principalities like China and America get along? Let’s approach this by way of segue. This was a fork in the road for human civilization. Our dear planet earth now becomes just but an optional resource on which we jostle for resources. By expanding to Mars, the jostle reduces for perhaps a couple of centuries of millenia. There need to be things that inspire you. Things that make you glad to wake up in the morning and say “I’m looking forward to the future.” And until then, we have gym and coffee – or perhaps gin & juice. We are going to have a golden age. One of the American values that I love is optimism. We are going to make the future good.#

The lowest layer—pure randomness—functions as a reminder that, no matter how much humans attempt to shape the world, Fortune remains untamed. The Fool in King Lear understands this instinctively, as do Hamlet and the various doomed messengers in the histories. Here, Shakespeare forces us to confront the terrifying arbitrariness of life: a single misplaced letter or a storm at the wrong moment can unmake kings. Hamlet’s final resignation to fate—his acceptance of the coin toss—marks his transition from an obsessive strategist to a man who sees randomness as the final authority. This moment is Shakespeare’s own reconciliation with the universe; he, too, ultimately acknowledges that some things simply happen without reason.

Layer 2 introduces a new game: poker, deception, and strategic uncertainty. Here, characters attempt to control the odds by manipulating perception. Iago is the undisputed master of this layer, recognizing that the key to victory is not brute force but the ability to make others believe they are acting of their own free will. Shakespeare’s comedies thrive in this space as well, turning identity itself into a game of misdirection. Viola in Twelfth Night and the machinations of The Merchant of Venice show that poker is not only about bluffing—it’s about knowing when the other players will call your bluff. Yet even in this layer, probability asserts itself in unexpected ways: Shylock, for all his legal cunning, fails to predict the one loophole that will undo him. The universe always holds a final card that cannot be seen.

The third layer—horse racing and Formula One—introduces momentum, a force that once initiated cannot be undone. Macbeth and Richard III begin as calculating players but quickly find themselves caught in runaway probabilities, their early bets compounding into irreversible trajectories. Shakespeare is particularly attuned to the way humans, once in motion, often find it impossible to stop; their past decisions constraining future ones, until they reach a point of no return. Macbeth’s realization that he is “stepped in blood” and must keep going is one of the most chilling expressions of probability’s grip on human affairs. Here, Shakespeare understands a fundamental truth about risk: once one starts racing, the track itself dictates the outcome.

Chess and war, occupying the fourth layer, elevate probability into structured strategy. These are the spaces of kings, generals, and political visionaries who believe they can control the board. Yet Shakespeare never allows them complete mastery. Brutus and Cassius miscalculate Antony’s rhetorical power. Hotspur, the aggressive tactician, underestimates the patient long-game of Prince Hal. Even in war and politics, uncertainty creeps in—ghosts from the past, unforeseen betrayals, and the sheer unpredictability of human emotion. Shakespeare’s kings are never pure chess players; they are haunted men, aware that even the best-laid plans can unravel.

Then, at the final layer, we reach romance—the place where probability itself dissolves into something larger. Love, for Shakespeare, is the ultimate game of uncertainty. Romeo and Juliet place the highest stakes on the lowest information, defying all odds for a feeling they cannot even fully understand. The lovers in Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Much Ado About Nothing engage in a dance where strategy and calculation falter. Love appears to be random, but Shakespeare’s comedies remind us that it always follows a hidden logic, leading inexorably to its resolution. The tragedies, by contrast, show what happens when love refuses to align with fate—when the dice are thrown, and the numbers come up against the lovers.

What Shakespeare achieves across these five layers is not merely an exploration of probability, but a profound meditation on the illusion of control. His characters oscillate between these layers, sometimes believing they are in a chess game when they are really in a poker match, or thinking they are in a war when they are actually just along for the ride. The fool who accepts randomness may be wiser than the king who believes he can master probability. Hamlet wavers between these states, never quite deciding whether he is playing a game of chess, poker, or simply waiting for fate to roll the dice for him.

This framework does not merely describe Shakespeare; it describes the human condition itself. Life, as he presents it, is not played on a single level. We are all gamblers in different ways—sometimes cautious strategists, sometimes reckless racers, sometimes deceivers, and sometimes romantics blind to the odds against us. And yet, no matter what game we think we are playing, the house—fortune, fate, the universe—always wins in the end.

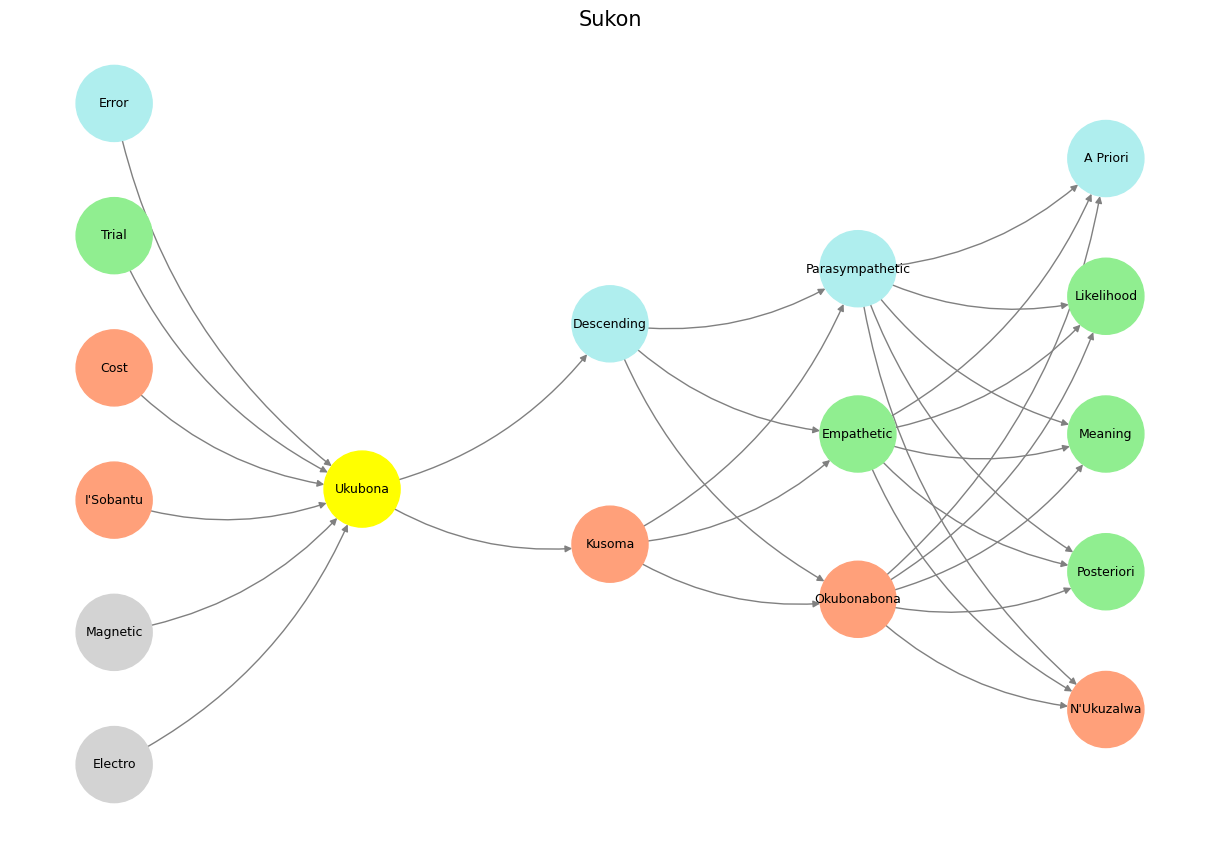

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Electro', 'Magnetic', "I'Sobantu", 'Cost', 'Trial', 'Error', ], # Veni; 95/5

'Mode': ['Ukubona'], # Vidi; 80/20

'Agent': ['Kusoma', 'Descending'], # Vici; Veni; 51/49

'Space': ['Okubonabona', 'Empathetic', 'Parasympathetic'], # Vidi; 20/80

'Time': ["N'Ukuzalwa", 'Posteriori', 'Meaning', 'Likelihood', 'A Priori'] # Vici; 5/95

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Ukubona'],

'paleturquoise': ['Error', 'Descending', 'Parasympathetic', 'A Priori'],

'lightgreen': ['Trial', 'Empathetic', 'Likelihood', 'Meaning', 'Posteriori'],

'lightsalmon': [

"I'Sobantu", 'Cost', 'Kusoma',

'Okubonabona', "N'Ukuzalwa"

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Sukon", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 36 Vita é Bella (ukubona). Questa é la mia storia (trial). Questo é il sacrificio (cost), che mia padro fece (sobantu). Questo esta il son dona pa me (error).#