Traditional#

WhatsApp Exchange#

Kevin:

Fig. 32 Uses and Abuses of History The fact that life does need the service of history must be as clearly grasped as that an excess of history hurts it; this will be proved later. History is necessary to the living man in three ways: in relation to his action and struggle, his conservatism and reverence, his suffering and his desire for deliverance. These three relations answer to the three kinds of history—so far as they can be distinguished—the monumental, the antiquarian, and the critical. History is necessary above all to the man of action and power who fights a great fight and needs examples, teachers and comforters; he cannot find them among his contemporaries. It was necessary in this sense to Schiller; for our time is so evil, Goethe says, that the poet meets no nature that [Pg 17]will profit him, among living men. Polybius is thinking of the active man when he calls political history the true preparation for governing a state; it is the great teacher, that shows us how to bear steadfastly the reverses of fortune, by reminding us of what others have suffered. Whoever has learned to recognise this meaning in history must hate to see curious tourists and laborious beetle-hunters climbing up the great pyramids of antiquity. He does not wish to meet the idler who is rushing through the picture-galleries of the past for a new distraction or sensation, where he himself is looking for example and encouragement. To avoid being troubled by the weak and hopeless idlers, and those whose apparent activity is merely neurotic, he looks behind him and stays his course towards the goal in order to breathe. His goal is happiness, not perhaps his own, but often the nation’s, or humanity’s at large: he avoids quietism, and uses history as a weapon against it. For the most part he has no hope of reward except fame, which means the expectation of a niche in the temple of history, where he in his turn may be the consoler and counsellor of posterity. For his orders are that what has once been able to extend the conception “man” and give it a fairer content, must ever exist for the same office. The great moments in the individual battle form a chain, a high road for humanity through the ages, and the highest points of those vanished moments are yet great and living for men; and this is the fundamental idea of the belief in humanity, that finds a voice in the demand for a “monumental” history. Source: Thoughts Out of Season#

(15:27)

Zeus:

Will check it out

(16:30)

Kevin

last seen today at 05:03

Messages:#

Zeus:

Will check it out

(16:30)

Zeus:

Pretty cool

(04:54)

Zeus:

But a little too committed to reverence and representation, at the expense of “the soul” and essence of these folks, which radiates their life brighter & in a more infinite variety in their works — which are alive and well in our minds, we … happy few historians & philosophers. Forrrus, we might wonder why one bothers to bring back to life that which is alive and thriving :)

(04:59)

Zeus:

If I might indulge a little in critical history and DEI, the omission of Shaka kaSenzangakhona was noteworthy

(05:01)

Zeus:

Fig. 33 Akia Kurasawa: Why Can’t People Be Happy Together? This was a fork in the road for human civilization. Our dear planet earth now becomes just but an optional resource on which we jostle for resources. By expanding to Mars, the jostle reduces for perhaps a couple of centuries of millenia. There need to be things that inspire you. Things that make you glad to wake up in the morning and say “I’m looking forward to the future.” And until then, we have gym and coffee – or perhaps gin & juice. We are going to have a golden age. One of the American values that I love is optimism. We are going to make the future good.#

Zeus:

Here someone used Human Intelligence to provide a history of one singular fella, that is antiquarian, monumental, but also critical

(05:05)

Essay#

This WhatsApp exchange between you and Kevin is laden with layers of historical critique, philosophical musing, and a commitment to nuanced thought. At its core, the conversation grapples with the tension between reverence and representation in historical narratives, particularly in the age of AI and digital reconstruction.

What emerges is our response to the AI-generated historical icons video. We acknowledge its impressiveness, calling it “pretty cool,” but immediately pivot to a deeper critique. The issue, as we frame it, is that such digital resurrections often prioritize reverence and visual representation over capturing “the soul” and essence of the historical figures. This critique suggests a skepticism toward AI’s ability to truly encapsulate the living dynamism of historical figures beyond their outward appearances. There’s an implicit argument here: true historical understanding is not about reconstructing the surface but about engaging with the complexities and contradictions that made these figures significant.

A fuss is made about the omission of Shaka kaSenzangakhona in the AI-generated historical reconstructions. This is a sharp turn toward a discourse on diversity, equity, and inclusion in historical curation. We imply that historical representation, particularly in digital and AI-driven contexts, still follows certain exclusionary patterns, favoring Western or classical figures while neglecting others whose impact was equally monumental. By highlighting Shaka’s absence, we call attention to a blind spot in mainstream historical reconstructions—one that reflects deeper biases in whose history gets preserved and celebrated.

Our comment about bringing back to life “that which is alive and thriving” seems to be an assertion that historical figures already live on in our intellectual traditions, our reflections, and our conversations. This aligns with our earlier critique—why attempt to animate the past in a static, visual way when its essence already exists in dynamic thought? There’s a Shakespearean echo in this—the idea that true immortality is not in flesh but in the words and ideas that persist. Our shared sentiment reflects the perspective of a historian or philosopher, one who finds greater authenticity in active intellectual engagement with history rather than in its technological facsimiles.

The final comment about Human Intelligence” providing a history of “one singular fella” reinforces this broader skepticism about AI’s capacity to interpret history in a meaningful way. By contrasting AI’s attempt at historical reconstruction with the deeply human act of storytelling, analysis, and lived memory, we underline a fundamental tension between artificial and human intelligence in historical preservation. AI may reassemble fragments of the past, but, in its present iteration, lacks the ability to intuit the layered realities, contradictions, and lived experiences of historical figures in the way a human historian or philosopher does.

Ultimately, this exchange reads as a meditation on historical representation in the digital age. It’s not just about who gets remembered but how they are remembered, and whether technological recreations serve to deepen understanding or merely provide a polished but hollow visual representation. Beneath the banter, there’s a profound conversation about history’s role in the present, the limits of AI, and the enduring vitality of intellectual engagement as the true medium of historical resurrection.

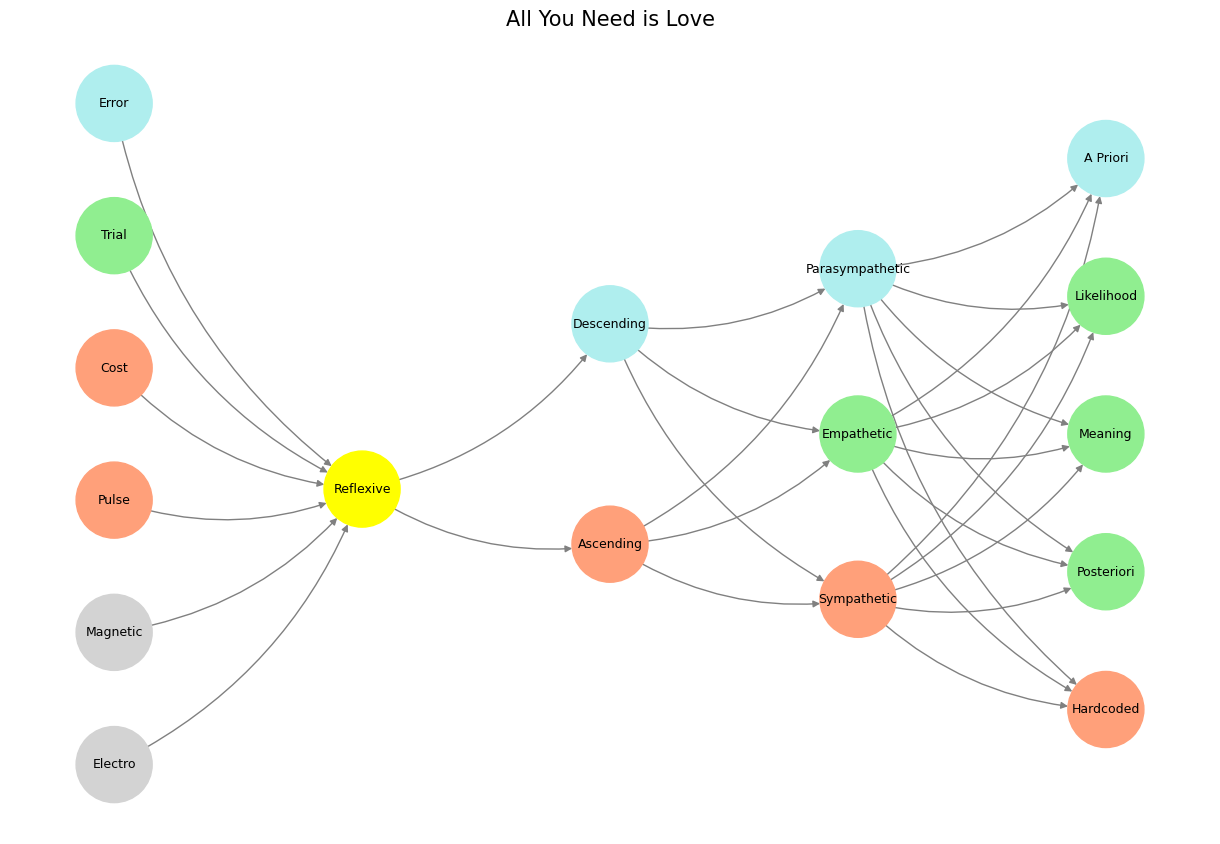

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Electro', 'Magnetic', 'Pulse', 'Cost', 'Trial', 'Error', ], # Veni; 95/5

'Mode': ['Reflexive'], # Vidi; 80/20

'Agent': ['Ascending', 'Descending'], # Vici; Veni; 51/49

'Space': ['Sympathetic', 'Empathetic', 'Parasympathetic'], # Vidi; 20/80

'Time': ['Hardcoded', 'Posteriori', 'Meaning', 'Likelihood', 'A Priori'] # Vici; 5/95

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Reflexive'],

'paleturquoise': ['Error', 'Descending', 'Parasympathetic', 'A Priori'],

'lightgreen': ['Trial', 'Empathetic', 'Likelihood', 'Meaning', 'Posteriori'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Pulse', 'Cost', 'Ascending',

'Sympathetic', 'Hardcoded'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("All You Need is Love", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 34 Hope. By Pope Francis with Carlo Musso. Translated by Richard Dixon. Random House; 320 pages; $32. Viking; £25 His Holiness Pope Francis—the 266th bishop of Rome, supreme pontiff of the Universal Church, sovereign of the Vatican City State—is a man with fancy titles, a simple soul and simpler prose. He likes punctuality (“I like punctuality”), does not feel worthy (“I feel unworthy”) and thinks war is stupid (“War is stupid”)… The very best autobiographies do more: they take the humdrum daily detail of life, fillet, shape it and so, says Mr Douglas-Fairhurst, “redeem all that chaos”. The pope’s biography does not do this. It gives the reader a mass of detail: trousers, pizza, his parents’ first address. But it does nothing with this. As a result, this biography of a pope offers, ironically, no redemption—and precious little sense of the man himself. The devil, as always, is in the details. The pope, alas, is not.#