Veiled Resentment#

The “play within the play” in Henry IV, Part 1—where Hal and Falstaff take turns role-playing King Henry IV—lays bare one of the most fascinating (and comedic) acts of usurpation in Shakespeare: Falstaff’s attempt to symbolically seize the throne, not through war or conspiracy, but through sheer charisma and improvisation.

When Falstaff and Hal act out the confrontation between father and son, Falstaff first plays King Henry, chiding Hal for his debauchery. But then, in a moment of meta-theatrical brilliance, he switches roles and plays Hal himself, making a bold claim for his own legitimacy:

“Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world!”

It’s a direct challenge to the narrative of the play itself. Henry IV’s entire arc is about securing power after usurping Richard II, and Hal’s journey is about proving himself worthy of the crown. But Falstaff is suggesting something radical—that the kingdom could belong to him instead. He is, in essence, attempting to rewrite the script, claiming a form of rule over Hal’s heart and even over England itself, not through noble birth or military conquest, but through wit, indulgence, and the sheer force of his larger-than-life personality.

This is a different kind of usurpation—not one based on violence or law, but on subversion and seduction. Falstaff is the ultimate populist, the man who wins over the commoners in the taverns of Eastcheap, the one who could rule, if only the world were different. And for a brief moment, in this “play within the play,” he does. He creates a vision of England where the king is not a distant, brooding figure obsessed with legitimacy, but a laughing, wine-soaked rogue who embodies life itself.

Fig. 22 The Next Time Your Horse is Behaving Well, Sell it. The numbers in private equity don’t add up because its very much like a betting in a horse race. Too many entrants and exits for anyone to have a reliable dataset with which to estimate odds for any horse-jokey vs. the others for quinella, trifecta, superfecta. The eternal recurrence of the same, as Nietzsche framed it, unfolds a cosmos devoid of beginning or end, an architecture where every output node circles back as input to an identical iteration, endlessly. In such a framework, the demand for moral purpose dissolves into absurdity. The cosmos, infinite in time and space, operates beyond binaries of good and evil, refusing to submit its vastness to human conceits of narrative closure. Yet Goethe’s defiance of moral demands, while celebrating the autonomy of the artist, rings hollow when confronted with the persistent itch for a conclusion, as Anthony Capella’s narrator discovers. To demand purpose from art, perhaps, is not to ruin it, but to humanize it, to tether infinite loops of meaning to a finite self yearning for understanding. In rejecting moral purpose, we may resist simplifying complexity, but we also risk severing art from its audience—an audience that, like Capella’s Victorian memoirist, craves resolution, even if only to satisfy itself. And so, while Nietzsche’s cosmos tumbles through its eternal recurrence, it must tolerate those who insist on finding lessons, a phenomenon less a contradiction than an inevitable consequence of human architecture mirroring the infinite. What have we learned? Perhaps only that the output of one iteration can be both conclusion and renewal, endlessly oscillating between the finite and the infinite.#

But Hal, deep down, knows this usurpation cannot last. The entire point of Henry IV is that Hal must abandon Falstaff—banishing him, quite literally, to become the king he is destined to be. The “play within the play” foreshadows the real moment of rejection in Henry IV, Part 2, when Hal, now Henry V, publicly renounces Falstaff with the devastating words:

“I know thee not, old man.”

Falstaff’s attempt at usurpation—his dream of ruling through mirth rather than might—fails, because history does not allow for kings like him. The world of Shakespearean history is one where legitimacy must be won through force, bloodlines, and sacrifice. But in that one scene, in the flickering firelight of the tavern, Falstaff does usurp Henry IV—if only for a moment, if only in play.

It is the tragedy of Falstaff that he believes his performance might become reality. But kingship, unlike theater, does not reward improvisation.

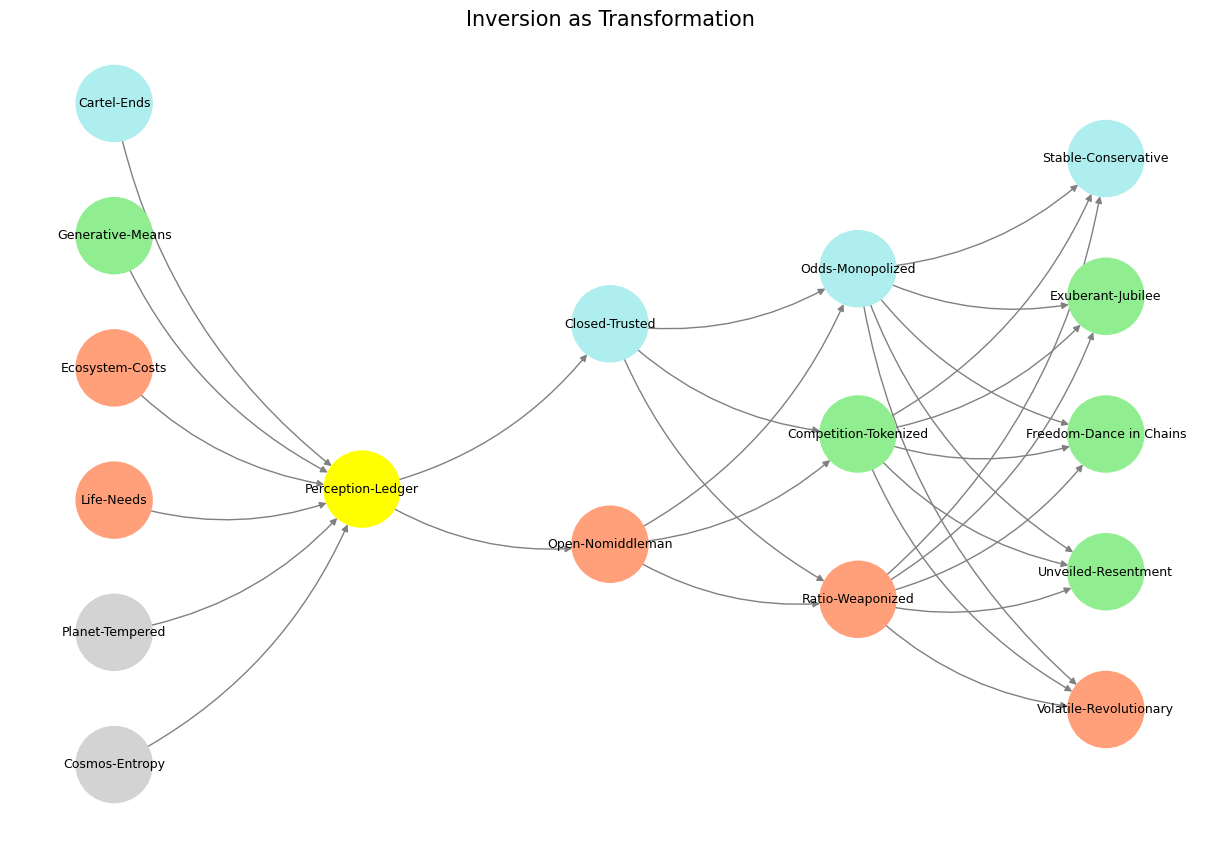

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'Planet-Tempered', 'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Generative-Means', 'Cartel-Ends', ], # Polytheism, Olympus, Kingdom

'Perception': ['Perception-Ledger'], # God, Judgement Day, Key

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Evil & Good

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Dynamics, Compromises

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Values

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Perception-Ledger'],

'paleturquoise': ['Cartel-Ends', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Generative-Means', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Open-Nomiddleman', # Ecosystem = Red Queen = Prometheus = Sacrifice

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Inversion as Transformation", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 23 Vet Advised When to Sell Horse. Right after an outstanding performance. Because you want to control how its perceived, the narrative backstory, and how its future performance might be imputed. Otherwise, reality manifests with point and interval estimates. This is the subject matter of the opening dialogue in Miller’s Crossing.#