Stable#

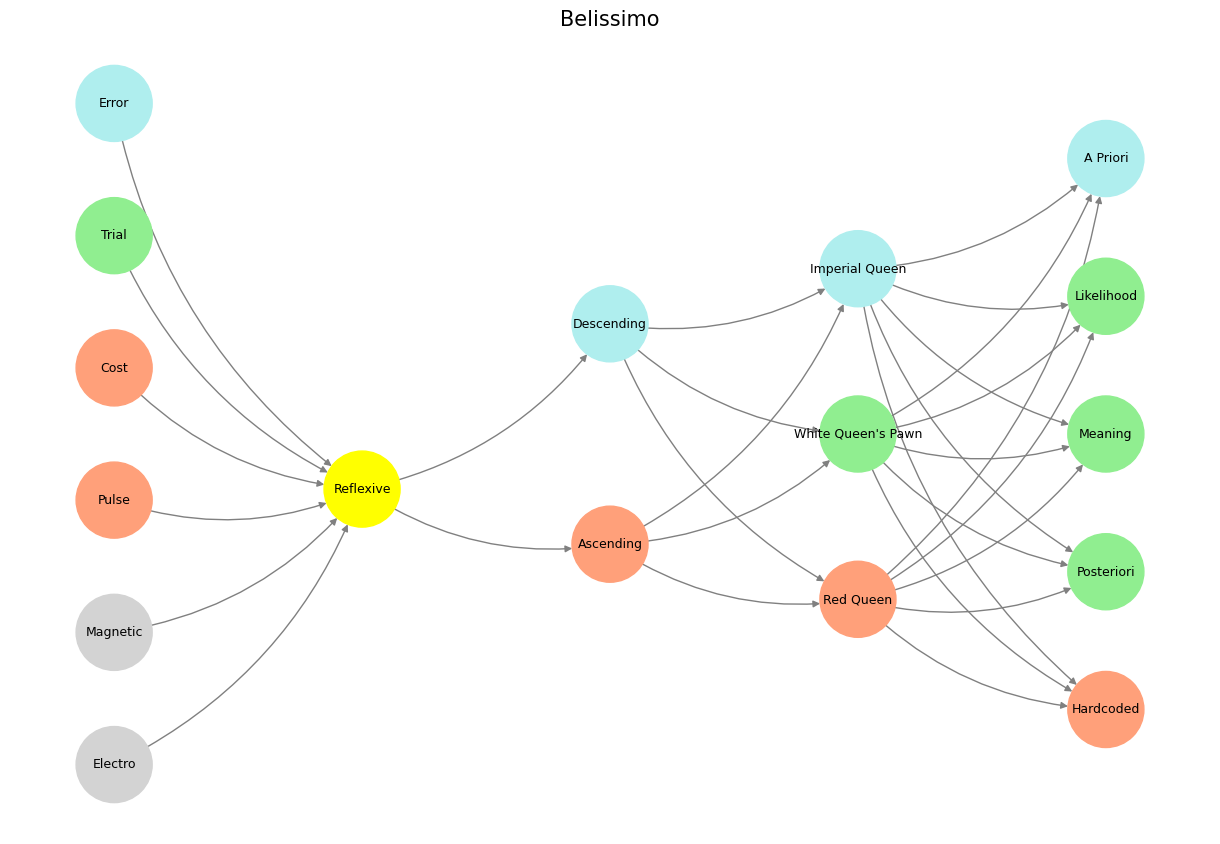

Somerset Maugham’s characterization of Elliott Templeton in The Razor’s Edge is a calculated dissection of a particular social type—an American who, despite his refined taste and aristocratic aspirations, remains forever outside the ancient hierarchies of Europe. Elliott is a green-node fella, iterative in his methods, forever refining and recalibrating, yet he masquerades as a paleturquoise fella, one of those who have already “arrived,” secure in the axioms of an inherited order. This distinction—between those who must navigate trial and error and those whose forebears settled life’s questions long ago—haunts Elliott’s carefully cultivated existence.

Maugham’s style in sketching Elliott is unrelentingly Wildean. Oscar Wilde, too, loved the contrast between old-world aristocrats and the nouveau riche Americans whose fortunes were made in “dry goods,” a faintly dismissive term for the practical, trade-driven economy that clashed with the leisurely traditions of Europe. Wilde’s American heiresses, richer than the scions of noble bloodlines yet dismissed for their lack of lineage, are mirrored in Elliott’s predicament. His wealth, his taste, and his social connections are impeccable, but he is tolerated rather than truly embraced. He is a dealer, a middleman, an interloper smoothing transactions between European aristocrats eager to discreetly liquidate their assets and the American museums hungry for prestige.

Fig. 37 There’s a demand for improvement, a supply of product, and agents keeping costs down through it all. However, when product-supply is manipulated to fix a price, its no different from a mob-boss fixing a fight by asking the fighter to tank. This was a fork in the road for human civilization. Our dear planet earth now becomes just but an optional resource on which we jostle for resources. By expanding to Mars, the jostle reduces for perhaps a couple of centuries of millenia. There need to be things that inspire you. Things that make you glad to wake up in the morning and say “I’m looking forward to the future.” And until then, we have gym and coffee – or perhaps gin & juice. We are going to have a golden age. One of the American values that I love is optimism. We are going to make the future good.#

Maugham exposes Elliott’s predicament with surgical precision. “People who did not like him,” the narrator remarks, “said he was a dealer,” a charge Elliott “resented with indignation.” His indignation, however, is revealing. Elliott moves among the old families of France and England, his “great culture and perfect manners” allowing him to broker the sale of Chippendale writing tables and Buhl cabinets. These transactions, though unspoken, taint him. Aristocrats in reduced circumstances need him, but they do not respect him. He profits, but one must be too well-bred to mention it. His role is necessary, but it ensures that he will never be one of them.

Here, the color-coded world of networks and equilibria clarifies Elliott’s fundamental tension. He is iterative, constantly refining his positioning, adjusting to market forces and social fluctuations—a classic green-node actor. But he must pretend to be paleturquoise, to have settled into the timeless elegance of European aristocracy. He dines with the best of them, serves vintage wines, offers an ambiance of old-world sophistication—but behind the scenes, pieces of his apartment vanish, replaced by others, their absence explained away with easy plausibility. The green-node man cannot escape his nature, though he constructs the illusion that he already belongs.

Maugham does not vilify Elliott, but he exposes the cracks in his performance. Wilde’s satire was often sharper, his Americans positioned as comic foils against a rigid and often ridiculous European aristocracy. But Maugham’s Elliott is tragic in his yearning. He is not a brash outsider demanding recognition; he is a supplicant, endlessly curating an identity that will never quite be accepted. His wealth, like that of the young American heiresses in Wilde’s plays, is undeniable, but his origins—rooted in the messy, transactional world of buying and selling—betray him.

Thus, Maugham’s Elliott embodies an eternal dialectic: the iterative striver versus the already-entrenched. He is not an aristocrat but an emissary of a world that will never fully claim him. The green-node fella, however much he masks himself in paleturquoise, remains, at heart, a dealer.

Razor’s Edge Structure#

W. Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge is a novel that, at first glance, appears to be a study of individual lives interwoven through love, loss, and the pursuit of meaning. However, its deeper structure, when properly decoded, reveals a game of identity played along an axis of European aristocracy, social ambition, and the rejection of both in favor of a path that embraces suffering as a gateway to enlightenment. The novel is an exercise in navigating the color-coded forces of pale turquoise, light green, and light salmon—the aristocratic lineage of Europe, the striving middle-class with its aspirational mimicry, and the radical renunciation of material success, respectively. These forces dictate the arcs of its central characters, particularly Elliott Templeton, Isabel Bradley, and Larry Darrell, whose trajectories define the novel’s essential structure.

European aristocracy, coded as pale turquoise, represents the realm of old-world refinement, inherited privilege, and the expectations that come with it. This is a social order that sees itself as the pinnacle of cultural achievement, and though the modern world may erode its power, it remains an aspirational ideal for those seeking legitimacy. Elliott Templeton, a consummate social climber, does not originate from this world but dedicates his life to approximating it. In truth, he belongs to the green category—a class of wealth without noble lineage, positioning himself within the European elite through careful association and impeccable taste. Yet, despite his success, he is never truly admitted into the highest echelons; his position is tolerated rather than embraced. He wears the robes of pale turquoise but can never fully embody its essence, leaving him in a perpetual state of yearning for inclusion.

Larry Darrell’s story begins within the green trajectory, engaged to Isabel Bradley, Elliott’s niece, whose aspirations align with the security and grandeur of her uncle’s social world. Larry, however, breaks from this trajectory, choosing instead the light salmon path—one of suffering, rejection of materialism, and the search for transcendental meaning. His experiences in war shatter the assumptions of his privileged youth, leading him away from the circles of power and into a life dedicated to understanding the nature of existence. Unlike Elliott, who strives to be recognized as aristocratic, Larry walks away from the very world that could offer him status and wealth. His movement into the light salmon category is not merely a personal choice but a metaphysical declaration: the aristocratic order and its middle-class imitators are hollow structures incapable of delivering true wisdom.

The tension in The Razor’s Edge is not just between individual characters but between the colors they embody. Isabel, like Elliott, belongs to the green category and views the pale turquoise world as the pinnacle of success. Her decision to remain within this realm, rejecting Larry’s alternative, is not just a choice of comfort over love but of structure over chaos. Larry’s path terrifies her because it represents an unmooring from the social coordinates that define her reality. In contrast, Elliott’s desperate need for recognition within the European aristocracy is ultimately revealed as hollow when, on his deathbed, his carefully curated status crumbles—his possessions remain, but the world he worshiped barely acknowledges his passing.

Maugham’s narrative, then, is a study of the friction between these different forces, each vying for supremacy in defining the purpose of life. In tracking the novel’s structure through the lens of these color-coded identities, it becomes evident that The Razor’s Edge is not simply a tale of one man’s spiritual journey but a coded critique of the hollowness of inherited power, the futility of social aspiration, and the arduous but ultimately rewarding pursuit of enlightenment. Larry, in embracing suffering, does what neither Elliott nor Isabel could—he transcends the entire system, escaping its false dichotomies and creating a new paradigm. In the end, his is the only path that leads beyond mere existence into something approaching the divine.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Electro', 'Magnetic', 'Pulse', 'Cost', 'Trial', 'Error', ], # Veni; 95/5

'Mode': ['Reflexive'], # Vidi; 80/20

'Agent': ['Ascending', 'Descending'], # Vici; Veni; 51/49

'Space': ['Red Queen', "White Queen's Pawn", 'Imperial Queen'], # Vidi; 20/80

'Time': ['Hardcoded', 'Posteriori', 'Meaning', 'Likelihood', 'A Priori'] # Vici; 5/95

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Reflexive'],

'paleturquoise': ['Error', 'Descending', 'Imperial Queen', 'A Priori'],

'lightgreen': ['Trial', "White Queen's Pawn", 'Likelihood', 'Meaning', 'Posteriori'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Pulse', 'Cost', 'Ascending',

'Red Queen', 'Hardcoded'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Belissimo", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 38 Icarus represents a rapid, elegant escape from the labyrinth by transcending into the third dimension—a brilliant shortcut past the father’s meticulous, earthbound craftsmanship. Daedalus, the master architect, constructs a tortuous, enclosed structure that forces problem-solving along a constrained plane. Icarus, impatient, bypasses the entire system, opting for flight: the most immediate and efficient exit. But that’s precisely where the tragedy lies—his solution works too well, so well that he doesn’t respect its limits. The sun, often emphasized as the moralistic warning, is really just a reminder that even the most beautiful, radical solutions have constraints. Icarus doesn’t just escape; he ascends. But in doing so, he loses the ability to iterate, to adjust dynamically. His shortcut is both his liberation and his doom. The real irony? Daedalus, bound to linear problem-solving, actually survives. He flies, but conservatively. Icarus, in contrast, embodies the hubris of absolute success—skipping all iterative safeguards, assuming pure ascent is sustainable. It’s a compressed metaphor for overclocking intelligence, innovation, or even ambition without recognizing feedback loops. If you outpace the system too fast, you risk breaking the very structure that makes survival possible. It’s less about the sun and more about respecting the transition phase between escape and mastery.#