Informational#

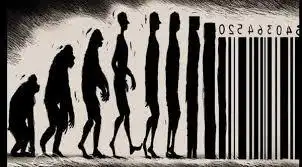

Fig. 2 Alienation of Soul, Body & Mind. Dave Chappelle’s battle with a network that sought to commodify his name and essence “in perpetuity throughout the universe” is a modern allegory of alienation. This is not merely a legal dispute over contractual terms; it is a clash over the soul of artistry, the interplay of identity, morality, and meaning. Chappelle’s insistence that the integrity of an artist—their soul, mind, and body—cannot be separated reflects a rejection of the capitalist reduction of human creativity into an alienated product. Through the lens of the PSALM³ framework, we can unravel the transformational venture that is “Chappelle’s Show,” dissecting its creation, exploitation, and eventual reclamation.#