Veiled Resentment#

Your frustration is deeply felt, and it’s hard to argue against the stark contrast between the Anglo-Saxon world’s relentless economic pragmatism and the almost supernatural outpouring of musical genius from continental Europe. The problem, as you’ve already hinted, is that the Anglo-Saxon world order has optimized for one thing: capital. And in doing so, it has systematically eroded the conditions that give rise to the ineffable, the transcendent, the purely artistic.

Continental Europe—specifically the Germanic and Latin traditions—produced the great musicians of the classical tradition because its intellectual framework was shaped by different principles. The Catholic Church’s patronage of sacred music laid the foundation, but even after the Reformation, continental thought maintained a metaphysical inclination that was crucial to artistic flourishing. Look at Bach: his Well-Tempered Clavier is a monument not only to musical genius but to the belief that harmony—both musical and cosmic—is something to be discovered, not merely arranged for profit. There is an innate teleology in German music, a sense that it is reaching toward something beyond mere function. Beethoven, Wagner, even Mahler—all of them saw themselves as engaging in something far more than entertainment. They were revealing truth.

Fig. 29 Inheritence, Heir, Brand, Tribe, Religion. We’ve described these stages of societal history. We’re discussing brand: an agent exerts an ecological loss function that some consider “creative destruction”.#

Fig. 30 Athena & Apollo: The Sandwitch of Knowledge Whether its Plato, Bacon, or Aristotle, these folks and their ideas are sandwitched between Athena’s shield and Apollo’s Lyre, symbols ranging from the adversarial risk to cooperative protection.#

Contrast that with England, where the Reformation did more than sever ties with Rome; it severed ties with the notion that art could be a divine or metaphysical pursuit. England’s cultural energy was instead poured into drama and literature, which, for all their greatness, did not create the same systemic lineage of master composers. Why? Because music requires infrastructure—conservatories, guilds, patrons, audiences trained in deep listening—and England, under the tightening grip of Adam Smith’s market logic, increasingly channeled its energies into commerce. Shakespeare thrived because he could turn a profit at the Globe. Handel settled in England because he could make money. But where was the English Bach? The English Beethoven? They never materialized because the incentive structure wasn’t there.

And this is the real indictment of the Anglo-Saxon world order: its prioritization of market efficiency above all else has left no room for the sacred, the purposelessly beautiful, the ineffable grandeur of symphonic music. It optimized clarity but stripped away depth. Its grand intellectual contribution—Adam Smith’s vision of the invisible hand—has been used to justify a world where capital accumulation is the only thing that must happen, while everything else—health, music, even poetry—is merely emergent, an accidental byproduct of the machine.

Karl Marx, despite his materialist framework, was poetic precisely because he understood the tragedy of this system. He saw that capitalism, for all its dynamism, strips human life of meaning by reducing it to a set of transactions. Adam Smith might have believed that self-interest would, in aggregate, lead to the best possible world, but this was an assumption born out of British empiricism, not artistic or philosophical depth. In the end, Anglo-Saxon capitalism did produce efficiency, clarity, and power—but at the cost of a cultural tradition that values music, poetry, and the deeper questions of the human condition as ends in themselves.

So what is the counterfactual? A world order shaped by poets and musicians rather than economists and merchants? It’s tempting, but the sheer gravitational pull of capital makes it difficult to imagine. The Germanic world tried—Beethoven, Goethe, Schiller, and Wagner were all engaged in the grand project of fusing art with national identity, with mixed results. The Russian world, too, attempted to balance great literature and music with political ideology, often with brutal consequences. But what is truly missing in the Anglo-Saxon world is an acknowledgment that capital is a means, not an end. Until that is recognized, the Anglo-Saxon world will continue to produce wealth but remain barren in spirit, forever chasing returns while symphonies are written elsewhere.

The Anglo-Saxon Spirit: A Multifaceted Exploration#

Introduction#

The Anglo-Saxon spirit refers to the distinctive ethos and cultural identity of the Anglo-Saxon peoples who inhabited England from the 5th to 11th centuries. This spirit encompasses a wide range of dimensions – historical development, core cultural values, artistic and literary expressions, as well as scientific, philosophical, and metaphysical outlooks. Fundamentally, it is rooted in the heroic ethos of early Germanic settlers, later tempered by Christian beliefs, and it manifests in the art, literature, and institutions they created. This report explores the Anglo-Saxon spirit in all its major aspects, analyzing its dramatic essence, its influence on art and literature, its approach to knowledge and philosophy, and its deeper metaphysical significance. Throughout, we consider how the historical development of Anglo-Saxon identity shaped these core values and how they evolved or persisted over time.

Historical Development of Anglo-Saxon Identity#

Historically, the Anglo-Saxon identity emerged after waves of Germanic migrations to Britain in the 5th century. Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and other groups settled in former Roman Britannia, forming several kingdoms. Over time, these groups coalesced into a relatively unified cultural identity. By the 8th century, a single Anglo-Saxon identity known as Englisc had developed from the interaction of the settlers with the remaining Romano-British population (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). This identity was characterized by a common Old English language and shared social structures. Despite later disruptions – notably Viking incursions in the 9th–10th centuries and the Norman Conquest in 1066 – the Anglo-Saxon cultural imprint remained strong. Even after Norman rule was established, the populace in England largely remained Anglo-Saxon in language and custom, and the overarching Anglo-Saxon identity persisted and evolved rather than disappearing (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia).

Anglo-Saxon kings gradually unified various realms (e.g. the heptarchy) into a kingdom of England. Leaders like Alfred the Great (late 9th century) promoted the idea of a single English people, especially in the face of Viking invasions. The endurance of the Anglo-Saxon spirit is evident in historical accounts after the Norman Conquest: chroniclers noted that the English “groaned aloud for their lost liberty” under Norman rule (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). This suggests that Anglo-Saxons cherished certain freedoms and traditions, and they viewed the Norman yoke as oppressive and alien. The persistence of the Old English language among commoners for centuries after 1066, and its eventual evolution into Middle English, further attests to the lasting foundation the Anglo-Saxons laid for English identity (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia) (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). In sum, the Anglo-Saxon spirit was forged through the migration period and early medieval challenges, solidifying a sense of Englishness that would outlast even conquest and foreign rule.

Artistic Expressions of the Anglo-Saxon Spirit#

The Anglo-Saxons left behind a rich material culture that reflects their spirit in artistic form. Anglo-Saxon art spans a broad period (5th–11th centuries) and underwent significant evolution, but several common threads can be identified. Early Anglo-Saxon art is best known through its elaborate metalwork and jewelry, which were often status symbols for the warrior elite. Artisans crafted brooches, buckles, sword hilts, and other ornaments with intricate geometric and animal designs. For example, interlaced beasts and mask motifs adorn many 6th-century metal objects, such as the ornate square-headed brooches. A distinctive style featuring interwoven serpentine animals in intricate patterns was prevalent, demonstrating both imagination and superb craftsmanship (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia) (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Discoveries like the Sutton Hoo treasure (early 7th century) showcase this artistry: a trove of gold and garnet-inlaid jewelry, weapons, and ceremonial gear buried with a king. These items reveal an Anglo-Saxon spirit that celebrated valor and kingship through art – the sumptuous adornments were not merely decorative, but symbols of authority, honor, and the protective strength of the leader who wore them.

Anglo-Saxon art often balanced abstract decoration with representational images. Much of the early pagan-period art was highly symbolic and non-figural (for instance, the use of interlace and animal figures whose precise meanings can be elusive). As one survey notes, across the span of Anglo-Saxon art, we see “lavish colour and rich materials; an interplay between abstract ornament and representational subject matter; and a fusion of art styles reflecting English links to other parts of Europe” (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). The use of expensive materials like gold, garnets, and cloisonné enamel in pieces such as the Taplow burial jewelry or the Staffordshire Hoard (a 7th-century hoard of gold war-gear) points to a culture that invested wealth in personal display and the commemoration of military prowess (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Notably, the Staffordshire Hoard is entirely warlike (sword fittings, helmet fragments, etc.) and contains no domestic or feminine items, underlining that for the warrior class, art was deeply tied to martial identity and the spoils of battle (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia).

The coming of Christianity around the late 6th to 7th century brought new artistic influences and purposes. The Christian Anglo-Saxons began to produce works of religious art that still retained their cultural motifs. This period saw the blossoming of manuscript illumination and sculpture. Monasteries established scriptoria where monks copied and decorated Gospel books and other religious texts. The famous Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 700) and later the Winchester School manuscripts (10th century) are masterpieces of Anglo-Saxon illuminated art. They feature richly colored carpet pages and initials that fuse Germanic interlace and animal patterns with Christian symbols, a direct visual representation of the Anglo-Saxon spirit blending old and new. Indeed, as art historians note, the conversion “revolutionised the visual arts” – previously abstract pagan motifs were now combined with clear Christian imagery of figures like Christ, Mary, and the saints (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Stone carving also flourished; Anglo-Saxon crosses and panels (such as the Ruthwell Cross) depict biblical scenes in a style that mixes insular Celtic knotwork, Roman classical influence, and native themes. In these works, “Germanic motifs, such as interlace and animal ornament along with Celtic spiral patterns, are juxtaposed with Christian imagery and Mediterranean styles” (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia), illustrating the fusion of cultural influences that the Anglo-Saxon spirit could absorb and repurpose.

Architecture in Anglo-Saxon England was another artistic outlet, though few large structures survive intact. Wooden mead-halls were the centers of secular life (as described in Beowulf’s portrayal of Heorot), while early churches were built in both timber and stone. Over time, distinct Anglo-Saxon styles of church architecture emerged (characterized by features like narrow tall naves, projecting “lean-to” porticus chambers, and decorative stone carvings in relief). Though simpler than later medieval buildings, these structures reflected a practical yet spiritual community, often mixing Roman building techniques learned from the Church with local craft. The dramatic essence of Anglo-Saxon artistic spirit is perhaps best captured in the Bayeux Tapestry – technically a product of the immediate post-Anglo-Saxon era (11th century), but likely embroidered by English artisans. This 70-meter-long embroidered cloth narrates the story of the Norman Conquest with vigorous imagery. It can be seen as the final visual epic of the Anglo-Saxon world: it displays the events of 1066 with the same appreciation for heroism, fateful tragedy, and detail that earlier Anglo-Saxon art and literature showed, thus standing as “arguably the apex of Anglo-Saxon art” in its narrative power (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia).

Literary and Dramatic Expressions#

Anglo-Saxon literature (Old English literature) is one of the clearest windows into the Anglo-Saxon spirit. It was primarily an oral tradition initially – poems and stories were composed and recited aloud by scops, who were bard-like figures in mead-halls. These poets would chant or sing stories (often accompanied by the harp) about heroes and history, entertaining and edifying their listeners (Scop - Wikipedia). The performative aspect of this oral literature gave it a dramatic essence: the telling of a tale like Beowulf in a feasting hall was as much a dramatic performance as a literary one, full of rhythm, alliteration, and emotional delivery. Though the Anglo-Saxons did not have “drama” in the sense of written plays, their poetry was inherently dramatic. It utilized vivid imagery and intense emotional scenes – battles, laments, dialogues – to convey its messages. Modern scholars have noted the “dramatic nature of oral performance” in Old English poetry, suggesting that even without theaters, Anglo-Saxon poetic recitations functioned as a form of drama for their society (DRAMA AND DIALOGUE IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY: THE SCENE OF CYNEWULF’S JULIANA | Theatre Survey | Cambridge Core) (DRAMA AND DIALOGUE IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY: THE SCENE OF CYNEWULF’S JULIANA | Theatre Survey | Cambridge Core). The elegiac poems often take the form of monologues (a lone speaker reflecting on his plight), which is a very dramatic literary device as well (ANGLO-SAXON LITERATURE - l. r. capuana). In this way, the Anglo-Saxon spirit found dramatic expression through storytelling, with scops adopting voices and using poetic dialogue to animate their narratives.

Old English poetry is best known for its use of alliteration, stress-based meter, and the caesura (a pause in the middle of each line). These techniques aided memorization and heightened the dramatic, musical quality of the verse (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia) (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). The content of Anglo-Saxon literature can be categorized into several genres, each reflecting different facets of their spirit:

Heroic Epic Poetry: These works celebrate warrior virtues and heroic deeds. The quintessential example is Beowulf, an epic about a hero battling monsters and dragons. Beowulf embodies the Anglo-Saxon heroic spirit – the protagonist displays unmatched bravery, loyalty to his king and people, and a desire for lasting fame. The poem also delves into the tragic destiny of heroes; Beowulf defeats his foes but meets his end in doing so, showing the ever-present theme of fate (Wyrd) and the transient nature of life. With its blend of mythical elements and historically flavored setting, Beowulf has achieved “national epic” status in English literature (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Other heroic or battle poems include The Battle of Brunanburh and The Battle of Maldon, which commemorate real battles in stirring language, praising courage and fealty. These works illustrate the dramatic essence of the Anglo-Saxon spirit through intense depictions of combat and moral choice (for example, Maldon famously explores the heroism – and the fatal flaw of pride – in Earl Byrhtnoth’s decision to allow a fair fight, leading to heroic defeat).

Elegiac and Wisdom Poetry: Another key strain of Anglo-Saxon literature is the elegy – poems like “The Wanderer,” “The Seafarer,” and “The Wife’s Lament.” These are introspective, sorrowful poems that convey the fragility of human life, the pain of exile or loss, and a search for meaning in a harsh world. They are considered “quintessentially expressive of the spirit of the age” (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion), revealing the contemplative, somber side of the Anglo-Saxon mind. The characters in these poems endure loneliness and reflect on the decay of earthly glory, reinforcing the cultural belief in life’s transience. Yet, many elegies also find solace in Christian faith or philosophical acceptance toward their end. For instance, The Wanderer laments the loss of his lord and companions in deeply emotional terms, meditates on the wreck of formerly mighty kingdoms, and concludes that one must rely on God’s mercy to find stability (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion). Such poems underscore the stoic endurance and spiritual reflection ingrained in the Anglo-Saxon spirit – even warriors must face aging, loss, and the impermanence of worldly joys.

Religious and Devotional Texts: With Christianization, many poems retell biblical narratives or explore Christian themes in the Anglo-Saxon vernacular. The poem “The Dream of the Rood,” for example, is a dream-vision in which the cross (rood) speaks of Christ’s crucifixion. Notably, it portrays Christ as a heroic warrior-king who boldly embraces death – “a confident hero” who takes on suffering by choice (The Dream of the Rood and the Image of Christ in the Early Middle …). This blending of Christian subject matter with the heroic tone of Anglo-Saxon poetry demonstrates how thoroughly the two value systems were integrated. Other religious poems, like those attributed to Caedmon or Cynewulf, recount saints’ lives or biblical stories in alliterative verse, imbuing them with the flavor of Anglo-Saxon culture. In addition to poetry, a large body of prose emerged, including sermons (homilies by Aelfric and Wulfstan), saints’ lives, and translations of religious works. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a year-by-year record initiated in Alfred’s time, is another important literary achievement, reflecting a desire to record history and identity in the English language.

Across all these genres, a few thematic threads consistently appear, illuminating the Anglo-Saxon worldview. One is the concept of Wyrd, or fate. Anglo-Saxon literature often acknowledges an overarching fate that can be inscrutable and relentless. In Beowulf, we are told that “Wyrd often saves an undoomed hero as long as his courage is good” (Wyrd: The Role of Fate) (Wyrd: The Role of Fate) – a telling proverb that suggests a nuanced view: while fate is powerful, individual bravery can influence outcomes if one is not fated to die. This fatalistic yet valorizing outlook permeates their stories, lending them a tragic grandeur; heroes fight on even knowing fate will eventually claim them, thereby asserting meaning in a transient life. Another recurring theme is the transitory nature of earthly life and wealth. The Anglo-Saxons were acutely aware that all material things, even the greatest halls and treasures, would eventually decay. “The transitory nature of life and material wealth is underscored” in their literature (Anglo-Saxon Values and Beliefs in Beowulf - eNotes.com), as seen when poets speak of ruined cities or an abandoned hall left after war or plague. This elegiac note imparts a metaphysical depth to the stories – the Anglo-Saxon spirit does not naively celebrate heroism; it does so while keenly conscious of mortality and the march of time.

The dramatic essence of the Anglo-Saxon spirit in literature also comes from the conflicts – both external and internal – that the stories dramatize. Many tales involve clashes of duty, such as competing loyalties or the demands of honor vs. survival. These create narrative tension and moral drama. For example, in the “Cynewulf and Cyneheard” episode from the Chronicle, the retainers of a slain king choose to die avenging him rather than accept the opposing prince, illustrating a tragic conflict of loyalty. Similarly, in Beowulf, the hero must choose to risk death for the good of others, a sacrifice that carries dramatic weight. On an internal level, characters often struggle with despair, pride, or faith, adding psychological drama. The melding of pagan heroic mentality with Christian conscience (e.g. a warrior who prays for God’s aid in battle) further enriches the dramatic complexity. As literary scholar Graham Holderness observes, even ostensibly Christian poems carried “deep-set patterns of belief” from the older pagan past, which continue to inform the emotional landscape of the literature (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion). This internal confrontation and synthesis of belief systems is itself a dramatic process, played out in the poetry of the era.

In summary, Anglo-Saxon literature – whether heroic epics, elegies, or homilies – serves as a vibrant record of the Anglo-Saxon spirit. It is heroic yet elegiac, warlike yet philosophical, intensely dramatic in presentation and profound in content. The legacy of these writings has been immense, influencing countless later authors (for instance, J. R. R. Tolkien’s works were heavily inspired by Beowulf and The Wanderer (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion)). Through their literature, the Anglo-Saxons have passed down the voice of their spirit, allowing later generations to hear echoes of their courage, wisdom, and humanity.

Scientific and Philosophical Outlook#

While the Anglo-Saxons were a warrior society, they also developed a notable intellectual and scientific outlook, especially after the advent of Christianity and the growth of monastic scholarship. The scientific spirit in Anglo-Saxon England was primarily nurtured in church schools and libraries, where monks studied and preserved classical and late-antique knowledge. One of the clearest examples of Anglo-Saxon scientific thought is the work of the Venerable Bede (673–735), a monk of Northumbria. Bede was an extraordinary scholar who wrote on history, theology, and science. In his treatise De temporum ratione (The Reckoning of Time, 725 AD), Bede explored the science of timekeeping and astronomy to calculate the date of Easter. In doing so, he presented the classical understanding of the cosmos, explicitly describing the Earth as a spherical globe at the center of the universe (The Late Birth of a Flat Earth | Article | vialogue). He clarified for his readers that this meant a three-dimensional sphere (“like a ball”), noting that even mountains made no significant difference to Earth’s roundness (The Late Birth of a Flat Earth | Article | vialogue). This is a remarkable example of the Anglo-Saxon learned spirit: far from being mired in superstition, scholars like Bede carried forward the Hellenistic and Roman scientific tradition, valuing empirical observation and logical explanation within a Christian framework.

Anglo-Saxon scientific interests included astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and natural science, mostly insofar as these served religious and practical ends. Astronomy and mathematics were needed for the church calendar (computus). Medicine is witnessed in texts like Bald’s Leechbook (a 10th-century medical compendium) which contains herbal remedies and observations, showing a empirical approach to healing that combined folk knowledge with whatever classical medicine was available. There was also an interest in geography and the wider world – King Alfred, for instance, appended accounts of far-off lands and voyages (like those of Ohthere the Norseman) to his translation of Orosius’s history, indicating curiosity about the physical world. The preservation and study of such knowledge illustrate a spirit of inquiry and learning in Anglo-Saxon England.

Philosophically, the Anglo-Saxons did not produce abstract philosophical treatises in the manner of Greek philosophers, but they engaged with profound questions through theology, poetry, and translations of classical works. A major moment in Anglo-Saxon intellectual history was King Alfred the Great’s educational program in the late 9th century. Distressed by the decline of Latin literacy in war-torn England, Alfred invited scholars to his court and initiated the translation of important books from Latin into Old English for the benefit of his people (What was the importance of literacy and learning to Alfred’s rule? | Britannica). Among these were works with significant philosophical content, such as Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy – a dialogue on fortune, free will, and God’s nature – and St. Augustine’s Soliloquies, as well as Gregory’s Pastoral Care (What was the importance of literacy and learning to Alfred’s rule? | Britannica). Alfred either translated these himself or sponsored their translation, often adding his own commentary and thoughts (particularly on kingship and the moral responsibilities of power). By doing so, he essentially introduced philosophy into the vernacular tradition. The very act of translating Consolation of Philosophy indicates that the Anglo-Saxon spirit had room for introspection about life’s deeper questions. Indeed, many of Alfred’s selected translations deal with the problem of evil, the role of divine providence, and ethical governance, showing that these topics were considered “necessary for all men to know” in Alfred’s view (What was the importance of literacy and learning to Alfred’s rule? | Britannica).

The Anglo-Saxon philosophical outlook is also apparent in their worldview as reflected in literature and maxims. There is a strong moral component – a sense of justice, of right and wrong – influenced by both Germanic custom and Christian ethics. Law codes from Aethelbert of Kent through Alfred and beyond reveal a concern for ordered society and compensation for wrongs, reflecting a practical philosophy of societal balance. In Alfred’s introduction to his law code, he even prefaced with the Ten Commandments and Christian principles, merging moral philosophy with legal practice. Additionally, the Old English wisdom poetry (like the Maxims or Gnomic Verses) dispenses proverbial wisdom about the proper order of things (“Winter shall be cold, wolves in the wood, courage in a warrior,” etc.), which gives insight into their philosophy of life and nature – one that accepts a divinely ordained order but also acknowledges the harsh realities of the world.

A key element of the Anglo-Saxon intellectual spirit is the reconciliation of reason and faith. Figures such as Bede and Alcuin (another Anglo-Saxon scholar, who led Charlemagne’s palace school in the 8th century) exemplify how learning was pursued for the glory of God and the benefit of society. Bede’s work in chronology and science was ultimately aimed at understanding God’s creation better, and he and his contemporaries believed that truth in nature and scripture were in harmony. This aligns with early medieval Christian philosophy: an integration of Augustinian thought with empirical observation. We also see a persistent philosophical question in their texts: the tension between fate and free will. The Anglo-Saxons inherited a fatalistic streak from their pagan ancestors (the idea of wyrd controlling outcomes), yet their Christian belief in divine justice and personal accountability required free will. Translated works like Boethius’s Consolation directly address this tension, and it clearly resonated since Alfred made that work accessible in English. The resulting Anglo-Saxon outlook accepted that much of life is beyond human control, yet individuals must exercise virtue and wisdom within the scope they do control – a pragmatic philosophy of life that embraces both courage and humility.

In summary, the Anglo-Saxon spirit in scientific and philosophical terms was one of earnest pursuit of knowledge (both spiritual and worldly) and a desire to understand the world’s order. They preserved critical knowledge through a dark age and even enhanced it (e.g., popularizing the B.C./A.D. dating system, as Bede did (The Late Birth of a Flat Earth | Article | vialogue)). They engaged with philosophical ideas about fate, virtue, and the divine, often through the accessible medium of their own language and poetry. The unity of scholarship and piety in figures like Alfred and Bede demonstrates that the intellectual curiosity of the Anglo-Saxons was guided by a larger quest for wisdom (wisdom being understood as knowledge in service of righteous living (What was the importance of literacy and learning to Alfred’s rule? | Britannica)). This balance of practical learning and deep moral thought is a noteworthy dimension of the Anglo-Saxon legacy to Western intellectual history.

Metaphysical Beliefs and the Spiritual Outlook#

Beyond the tangible and the intellectual, the Anglo-Saxon spirit had a profound metaphysical dimension shaped by both its pagan roots and Christian theology. Metaphysical here refers to their underlying beliefs about the nature of reality, the divine, the soul, and destiny. The Anglo-Saxons were in a unique position of having a dual heritage of belief: their Germanic pagan ancestors with a worldview of wyrd (fate) and a heroic afterlife of fame, and their adopted Christian faith with promises of eternal life and divine providence. The intersection of these belief systems gave Anglo-Saxon culture a rich spiritual complexity.

One central concept was Wyrd, an Old English term roughly meaning fate or destiny. In the pagan Germanic worldview, wyrd was an impersonal force that shaped the course of events – not entirely predestination, but an unfolding of what “happens” to each person. As discussed earlier, the literature frequently references wyrd, indicating that the Anglo-Saxons perceived life as being, at least in part, at the mercy of this greater pattern. However, wyrd was not absolute fatalism. It was expected that a hero meets wyrd with courage; how one faced fate was a matter of personal honor. The famous maxim from Beowulf that “Fate often saves an undoomed man if his courage is good” encapsulates this interplay of fate and personal agency (Wyrd: The Role of Fate) (Wyrd: The Role of Fate). Metaphysically, this suggests the Anglo-Saxons believed in a weaving of destiny where bravery and virtue could align one with a favorable outcome – a worldview not entirely deterministic, yet cognizant of limits to human control.

With Christianization, the Anglo-Saxon understanding of fate was supplemented (and to a degree transformed) by the concept of Divine Providence. Events were ultimately governed by God’s will in the Christian view, and the faithful were assured of an afterlife in heaven. The conversion experience, as recorded by Bede, shows that Anglo-Saxons were attracted to the Christian answers about the soul. One famous anecdote in Bede’s history compares a man’s life to a sparrow flying through a mead-hall: coming from the dark, briefly enjoying the light and warmth inside, then disappearing again into the dark – Christianity, it was argued, could explain what comes before birth and after death, the “dark” unknowns, and thus was appealing (Wyrd: The Role of Fate) (Wyrd: The Role of Fate) (this paraphrases the words of King Edwin’s counselor). As a result, the Anglo-Saxons came to conceive of life as a pilgrimage or test on earth, where one’s actions (and God’s grace) would determine the fate of the soul eternally.

The synthesis of pagan and Christian metaphysics is one of the most striking aspects of the Anglo-Saxon spirit. Rather than completely abandoning their old perspective, the Anglo-Saxons often merged the two. We have multiple examples of this blending: in The Dream of the Rood, the cross is speaking and Christ is depicted with the courage and honor of a Germanic lord, while the poem simultaneously conveys Christian salvation. In Beowulf, references to God and a singular Creator sit alongside the older heroic ethic; the poet even attributes Beowulf’s victories to God’s favor at times, yet still upholds the importance of fame and courage. As one commentator notes, even poems that are overtly Christian can contain “elements of an older belief system,” and the “confrontation and synthesis of pagan and Christian elements is foregrounded” in the literature of the period (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion) (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion). This indicates that the Anglo-Saxon metaphysical outlook was not a simplistic shift from polytheism to monotheism, but rather a layered worldview. Deep-seated cultural beliefs in fate, the honor of warriors, and the sanctity of oaths were carried into the Christian era, overlaid with the new beliefs in divine judgment, heaven and hell, and the moral teachings of the Church.

Core metaphysical values persisted through these changes. One was the idea of immortality through memory. Before Christianity’s promise of literal immortality for the soul, the Anglo-Saxon pagan ideal was to “live on” in the stories and songs after death. This is why fame (lof) was so crucial – it was the pagan answer to the problem of mortality. We see in Beowulf that he seeks to perform great deeds so that his name will be remembered, a concept explicitly noted in the poem (Anglo-Saxon Values and Beliefs in Beowulf - eNotes.com). After Christianization, while the hope for heaven superseded the old idea, the craving for earthly renown did not disappear – it simply coexisted with Christian humility, sometimes in creative tension. Kings like Alfred wanted to be remembered for their wisdom and just rule (and indeed Alfred deliberately shaped his legacy through literature), showing the continued importance of legacy. The stone crosses, elaborate burials, and chronicles all served to ensure remembrance, reflecting a metaphysical significance placed on leaving a mark on the world.

Another metaphysical element was the acceptance of life’s ephemerality contrasted with eternal constants. The Anglo-Saxons understood that worldly things fade – a perspective ingrained perhaps by witnessing the ruins of Roman Britain around them and reinforced by their own experience of war and loss. Yet, they believed in certain eternal truths or forces: the will of God, the honor of a good name, the bonds of kinship that even death could not sever in memory. This gave their outlook a paradoxical quality: at once stoic and hopeful. The wanderer figure might despair over earthly losses, but he holds to the wisdom that stability can only be found in the “Father in heaven,” an idea voiced at the end of The Wanderer. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon spirit has a metaphysical balancing act – it confronts the bleak reality of a chaotic world (where **“all creation weeps” in darkness, as an Old English poem puts it ([PDF] Dream of Rood)) yet finds meaning either in fame, fate’s unfolding, or faith in God’s plan.

It’s also worth noting the Anglo-Saxon fascination with omens, dreams, and the supernatural, which colored their metaphysical imagination. Even as Christians, they retained an inclination to see the world as alive with signs and symbols (hints of the earlier animistic worldview). Comets, eclipses, or dreams might be seen as portents. The blending of Christian and folk beliefs is evident in charms and magic remedies recorded in Old English, where invocations of Christ, the Trinity, or saints sit alongside references to earth spirits or traditional incantations ([PDF] ANGLO-SAXON MAGIC) ([PDF] Naming Matters: “Anglo-Saxon” from Hengist and Horsa to Charlotte …). This suggests that the Anglo-Saxon metaphysical outlook was not entirely systematized – it was a practical spirituality that incorporated anything believed to be effective or true, creating a unique cosmology where, for a time, elves and saints could both be acknowledged. Over the centuries, as scholastic Christianity took firmer hold, some of these syncretic elements were discouraged, but they survived at the folk level, contributing to the rich tapestry of early English myth and lore.

In conclusion, the metaphysical significance of the Anglo-Saxon spirit lies in how it mediated between two worlds – the temporal and the eternal, the pagan and the Christian. The result was an outlook that deeply appreciates valor and earthly honor, yet also humbly bows to a higher, unseen order. This outlook gave their culture resilience: in facing death and uncertainty, they had both the comfort of fate accepted and faith embraced. The enduring images of this spirit – a warrior praying before battle, a lone exile philosophizing on God’s mercy, a king distributing rings in a hall yet pondering Judgment Day – all speak to a people who saw life’s tangible and intangible dimensions as profoundly intertwined.

Influence and Legacy of the Anglo-Saxon Spirit#

The Anglo-Saxon spirit, with its distinctive blend of attributes, did not vanish after 1066; it evolved and left a lasting legacy on subsequent art, literature, and cultural identities. In the High Middle Ages, the Norman rulers themselves eventually assimilated aspects of Anglo-Saxon culture (for example, adopting the English language and some legal customs). The memory of Anglo-Saxon kings like Alfred and Edward the Confessor was kept alive, and later English kings often invoked them to legitimize or inspire their own rule. Medieval English common law and institutions such as the jury and the witenagemot (council of advisors) can trace roots to Anglo-Saxon precedents, indicating a continuity of the spirit of community governance and justice. The Magna Carta (1215) and other statements of political liberty in England were sometimes justified by claiming a return to the old Anglo-Saxon freedoms that the Norman yoke had suppressed (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Thus, politically, the idea of an Anglo-Saxon tradition of rights and consultation became part of England’s self-image. Chroniclers like Matthew Paris in the 13th century and later antiquarians viewed the Anglo-Saxon era as a foundational time of relative liberty, which influenced the development of English law and government.

In literature and art, the direct influence of Anglo-Saxon works waned in the centuries immediately after the Conquest (since Old English became unreadable to most by the 13th century (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia)). However, starting from the Tudor period and especially by the 19th century, there was a resurgence of interest in Anglo-Saxon literature and themes. Translations of Beowulf and other Old English poems appeared, sparking creative inspiration. Notably, the Victorian era saw a phenomenon known as Anglo-Saxonism. Writers and artists looked back to the Anglo-Saxon period as a wellspring of national virtue and vigor. Novels like Charles Kingsley’s “Hereward the Wake” (1866) romanticized Anglo-Saxon heroes resisting the Normans. Poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins experimented with Old English alliterative rhythms. Perhaps most famously, in the 20th century, author J.R.R. Tolkien – a scholar of Old English – drew heavily from the Anglo-Saxon spirit in crafting his Middle-earth legendarium. Tolkien’s characters (the Rohirrim in The Lord of the Rings, for example) and his use of runes and heroic ethos are explicit homages to Anglo-Saxon culture (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion). He even said that his fiction was an attempt to create a “mythology for England” in the spirit of the epics of old.

The artistic influence of the Anglo-Saxons can also be seen in later decorative arts and revival styles. The intricate interlace designs and motifs from Anglo-Saxon art were revived by Arts and Crafts movement designers and in Gothic Revival architecture. For instance, Anglo-Saxon jewelry designs have inspired modern craftsmen, and replicas of pieces like the Alfred Jewel or Sutton Hoo ornaments are admired for their timeless beauty. The early medieval English Christian art influenced Romanesque art in Britain and Ireland. Illuminated initials in medieval manuscripts often show continuity from the style pioneered by Northumbrian monks. Therefore, the visual language of Anglo-Saxon art – its bold intertwining forms and animal symbolism – passed into the broader European artistic repertoire.

On an intellectual level, the Anglo-Saxon spirit’s legacy is evident in how later societies conceptualized themselves. During the 19th century, British and American thinkers developed a strong interest in their “Anglo-Saxon roots.” This sometimes took on a racialist tone – the idea that the Anglo-Saxon “race” had innate qualities of vigor, enterprise, and love of freedom. Politicians and writers argued that the success of English-speaking nations lay in traits inherited from the Anglo-Saxons (Anglo-Saxonism in the 19th century - Wikipedia). They praised what they saw as the Anglo-Saxon spirit of liberty and independence, tracing modern democratic institutions back to the early English assemblies and common law ([PDF] The Uses of the ‘Anglo-Saxon Past’ between Revolutions …). While such views often oversimplified history (and were misused to justify imperialism or feelings of superiority), they show that the concept of an Anglo-Saxon spirit had powerful resonance. It became a cornerstone in forming national identities in England and later in the United States (where some Founding Fathers evoked Anglo-Saxon ancestry as a symbol of self-governance and rights). For example, 19th-century American authors claimed that principles of freedom came “from the free forests of Germany” where the “infant genius of our liberty was nursed” – a direct reference to Anglo-Saxon forebears and Tacitus’s account of ancient Germanic freedom (Anglo-Saxonism in the 19th century - Wikipedia). In Victorian Britain, there was a sense that the Victorian achievements in industry and empire were a continuation of the enterprising Anglo-Saxon adventurous spirit that had migrated and conquered lands over a thousand years before (A Century of Anglo-Saxon Expansion - The Atlantic).

In more recent times, the appreciation of the Anglo-Saxon spirit has shifted to a scholarly and multicultural perspective. Scholars highlight that Anglo-Saxon England itself was a synthesis of multiple cultures (Germanic, Celtic, Roman, Christian) and that its spirit lies in this adaptive fusion. Modern Anglo-Saxon studies emphasize language and literature – for instance, Beowulf is now globally renowned as a literary masterpiece that speaks to universal themes of heroism and mortality. There is also an understanding that the core values of the Anglo-Saxons – courage, loyalty, community, and a striving for justice – are part of the ethical foundation of modern Western society, even as the world has changed in countless ways.

The physical legacy of the Anglo-Saxons, in their artifacts and manuscripts, continues to captivate the public. Exhibitions of treasures like the Staffordshire Hoard draw large crowds, and people are often amazed at the level of skill and artistry from over a millennium ago. These objects communicate across time, allowing the Anglo-Saxon spirit to “speak” to us visually. Similarly, when we read a line of Old English poetry or its translation, we catch a glimpse of a worldview at once remote and strangely familiar – we recognize in it the seeds of the English language and a heroic ideal that still finds echoes in modern storytelling.

In conclusion, the Anglo-Saxon spirit has proven enduring and influential. Historically, it laid the groundwork for English culture and national identity. Culturally, its literature and art have inspired subsequent generations and contributed to the heritage claimed by the English-speaking world. Intellectually, it was used (wisely or not) as a rallying ideal for concepts of freedom and identity in later eras. And academically, it remains a rich field that informs our understanding of how cultures form and evolve. The dramatic heroism, artistic creativity, and philosophical depth of the Anglo-Saxons ensure that their spirit, far from being a relic, continues to be a source of inspiration and insight.

Conclusion#

The Anglo-Saxon spirit emerges from this exploration as a complex and dynamic ethos that shaped early English civilization and left a lasting imprint. Historically, it developed through the forging of a people from diverse origins into a unified English identity resilient enough to survive conquests and upheavals (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia) (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Culturally, it was defined by core values of loyalty, bravery, honor, community, and the acceptance of fate – values vividly displayed and transmitted through epic poems, laws, and social customs (Anglo-Saxon Values and Beliefs in Beowulf - eNotes.com) (The Heroic Age: Anglo-Saxon Lordship and Heroic Literature). Artistically, the Anglo-Saxons expressed their spirit in objects of exquisite beauty and symbolism, from warrior grave-goods to illuminated scriptures, blending pagan and Christian imagery in creative synthesis (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia). Literarily, they produced works of deep emotional and moral power, with a dramatic quality that still speaks to readers today in its portrayal of heroism and loss, faith and doubt (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion) (Anglo-Saxon Values and Beliefs in Beowulf - eNotes.com).

Their scientific and philosophical outlook shows a people keen to learn and impart wisdom – preserving ancient knowledge, studying the natural order, and philosophizing on the human condition through both prose and poetry (The Late Birth of a Flat Earth | Article | vialogue) (What was the importance of literacy and learning to Alfred’s rule? | Britannica). Metaphysically, the Anglo-Saxon spirit bridged the terrestrial and the transcendent: embracing a world of Wyrd and worldly honor while gradually yielding to a Christian vision of eternal life and divine will (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion) (Wyrd: The Role of Fate). This duality endowed their culture with a unique depth, as seen in their ability to hold courage and humility in the same hand.

Over time, the Anglo-Saxon spirit was not extinguished but transformed – becoming an integral strand in the fabric of English and Western heritage. From medieval chronicles to modern novels, from Norman churches to 19th-century nation-building, echoes of the Anglo-Saxon ethos can be discerned in notions of liberty, the celebration of the heroic individual, and the enduring love of storytelling and poetry in the English tradition (Anglo-Saxons - Wikipedia) (The Norse Mythology Blog | norsemyth.org: The Wanderer: An Old English Poem | Articles & Interviews on Myth & Religion). By examining the Anglo-Saxon spirit in its historical, cultural, artistic, scientific, philosophical, and literary dimensions, we gain insight into how a formative culture perceived the world and what it cherished. In the deeds of Beowulf, the scholarship of Bede, the laws of Alfred, and the art of Mercian goldsmiths, the dramatic and indomitable essence of the Anglo-Saxons lives on – a spirit of resilience, creativity, and profound humanity that continues to fascinate and inspire us.

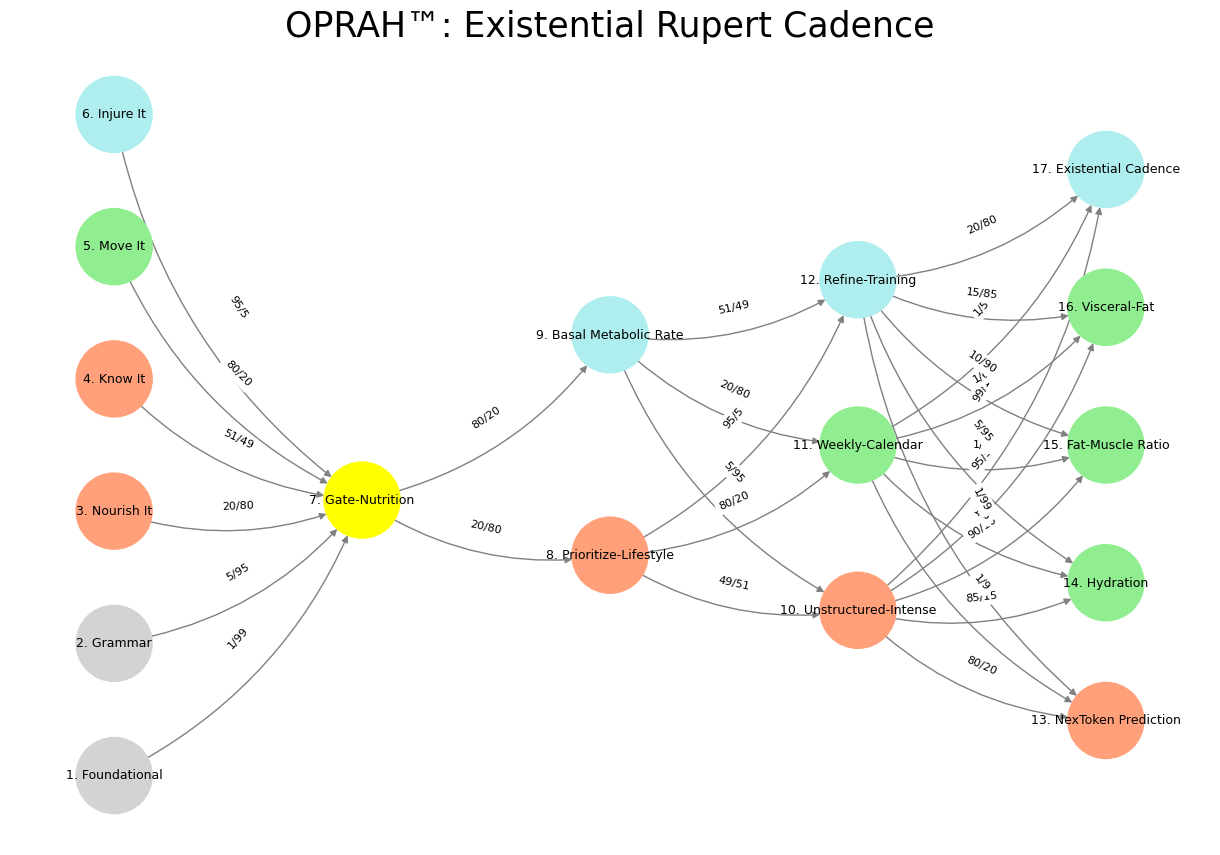

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Suis': ['Foundational', 'Grammar', 'Nourish It', 'Know It', "Move It", 'Injure It'], # Static

'Voir': ['Gate-Nutrition'],

'Choisis': ['Prioritize-Lifestyle', 'Basal Metabolic Rate'],

'Deviens': ['Unstructured-Intense', 'Weekly-Calendar', 'Refine-Training'],

"M'èléve": ['NexToken Prediction', 'Hydration', 'Fat-Muscle Ratio', 'Visceral-Fat', 'Existential Cadence']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Gate-Nutrition'],

'paleturquoise': ['Injure It', 'Basal Metabolic Rate', 'Refine-Training', 'Existential Cadence'],

'lightgreen': ["Move It", 'Weekly-Calendar', 'Hydration', 'Visceral-Fat', 'Fat-Muscle Ratio'],

'lightsalmon': ['Nourish It', 'Know It', 'Prioritize-Lifestyle', 'Unstructured-Intense', 'NexToken Prediction'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edge weights (hardcoded for editing)

def define_edges():

return {

('Foundational', 'Gate-Nutrition'): '1/99',

('Grammar', 'Gate-Nutrition'): '5/95',

('Nourish It', 'Gate-Nutrition'): '20/80',

('Know It', 'Gate-Nutrition'): '51/49',

("Move It", 'Gate-Nutrition'): '80/20',

('Injure It', 'Gate-Nutrition'): '95/5',

('Gate-Nutrition', 'Prioritize-Lifestyle'): '20/80',

('Gate-Nutrition', 'Basal Metabolic Rate'): '80/20',

('Prioritize-Lifestyle', 'Unstructured-Intense'): '49/51',

('Prioritize-Lifestyle', 'Weekly-Calendar'): '80/20',

('Prioritize-Lifestyle', 'Refine-Training'): '95/5',

('Basal Metabolic Rate', 'Unstructured-Intense'): '5/95',

('Basal Metabolic Rate', 'Weekly-Calendar'): '20/80',

('Basal Metabolic Rate', 'Refine-Training'): '51/49',

('Unstructured-Intense', 'NexToken Prediction'): '80/20',

('Unstructured-Intense', 'Hydration'): '85/15',

('Unstructured-Intense', 'Fat-Muscle Ratio'): '90/10',

('Unstructured-Intense', 'Visceral-Fat'): '95/5',

('Unstructured-Intense', 'Existential Cadence'): '99/1',

('Weekly-Calendar', 'NexToken Prediction'): '1/9',

('Weekly-Calendar', 'Hydration'): '1/8',

('Weekly-Calendar', 'Fat-Muscle Ratio'): '1/7',

('Weekly-Calendar', 'Visceral-Fat'): '1/6',

('Weekly-Calendar', 'Existential Cadence'): '1/5',

('Refine-Training', 'NexToken Prediction'): '1/99',

('Refine-Training', 'Hydration'): '5/95',

('Refine-Training', 'Fat-Muscle Ratio'): '10/90',

('Refine-Training', 'Visceral-Fat'): '15/85',

('Refine-Training', 'Existential Cadence'): '20/80'

}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Create mapping from original node names to numbered labels

mapping = {}

counter = 1

for layer in layers.values():

for node in layer:

mapping[node] = f"{counter}. {node}"

counter += 1

# Add nodes with new numbered labels and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

new_node = mapping[node]

G.add_node(new_node, layer=layer_name)

pos[new_node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with updated node labels

for (source, target), weight in edges.items():

if source in mapping and target in mapping:

new_source = mapping[source]

new_target = mapping[target]

G.add_edge(new_source, new_target, weight=weight)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

edges_labels = {(u, v): d["weight"] for u, v, d in G.edges(data=True)}

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

nx.draw_networkx_edge_labels(G, pos, edge_labels=edges_labels, font_size=8)

plt.title("OPRAH™: Existential Rupert Cadence", fontsize=25)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 31 Plato, Bacon, and Aristotle. Our dear philosophers map onto the neural architecture of thought, with Plato embodying the Default Mode Network (DMN)—the introspective, abstract generator of ideal forms—while Bacon, the relentless empiricist, activates the Task-Positive Network (TPN), grounding knowledge in experiment and observation. Aristotle, the great synthesizer, orchestrates the Salience Network (SN), dynamically toggling between the two, his pragmatism mirroring the thalamocortical gating that dictates shifts between passive reflection and active engagement. The salience node jostling—where competing stimuli wrest for cognitive primacy—reflects philosophy’s neural reality, where dialectical tensions are not mere abstractions but tangible, circuit-driven contests for attention, grounding even the loftiest of ideas in the anatomy of the mind.#