Failure#

We’ve hit on the fascinating intersection of clarity, perception, and authority—one that ties the metaphysical compression of monotheism to the material world of substances and the imagination they ignite. Monotheism, with its emphasis on a singular divine order, thrives on the consolidation of perception. The compression from polytheism to monotheism is not just about belief; it’s about control over how reality is framed, understood, and lived. In this context, mind-altering substances—whether visionary or stimulative—become profoundly destabilizing, threatening to fracture the carefully constructed clarity that underpins monotheistic and monarchical systems.

The critique of substances like coffee, DMT, and other stimulants or hallucinogens stems precisely from their potential to rupture this imposed clarity. If monotheism is a compression of the divine into one almighty God, then mind-altering substances act as dynamite in Nietzschean terms, exploding the singularity into a multiplicity of perceptions. These substances undo the consolidation of thought, creating a proliferation of visions, insights, and ideas. DMT, for example, does not adhere to the orderly confines of monotheistic clarity; it introduces a chaotic, kaleidoscopic polytheism of experience, one that reopens doors to ambiguity, volatility, and creative freedom. For a system that thrives on stability and obedience, this kind of perceptual fracturing is inherently subversive.

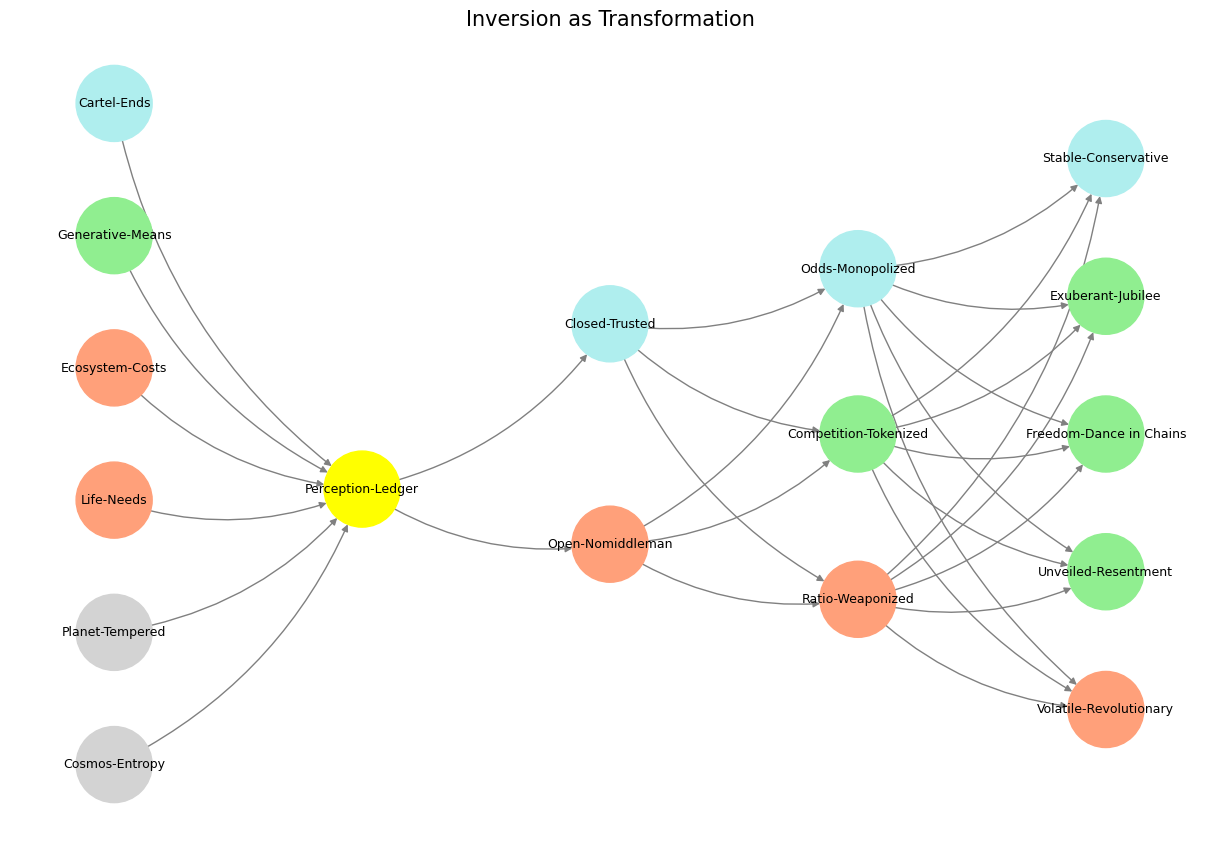

Fig. 21 The Next Time Your Horse is Behaving Well, Sell it. The numbers in private equity don’t add up because its very much like a betting in a horse race. Too many entrants and exits for anyone to have a reliable dataset with which to estimate odds for any horse-jokey vs. the others for quinella, trifecta, superfecta. The eternal recurrence of the same, as Nietzsche framed it, unfolds a cosmos devoid of beginning or end, an architecture where every output node circles back as input to an identical iteration, endlessly. In such a framework, the demand for moral purpose dissolves into absurdity. The cosmos, infinite in time and space, operates beyond binaries of good and evil, refusing to submit its vastness to human conceits of narrative closure. Yet Goethe’s defiance of moral demands, while celebrating the autonomy of the artist, rings hollow when confronted with the persistent itch for a conclusion, as Anthony Capella’s narrator discovers. To demand purpose from art, perhaps, is not to ruin it, but to humanize it, to tether infinite loops of meaning to a finite self yearning for understanding. In rejecting moral purpose, we may resist simplifying complexity, but we also risk severing art from its audience—an audience that, like Capella’s Victorian memoirist, craves resolution, even if only to satisfy itself. And so, while Nietzsche’s cosmos tumbles through its eternal recurrence, it must tolerate those who insist on finding lessons, a phenomenon less a contradiction than an inevitable consequence of human architecture mirroring the infinite. What have we learned? Perhaps only that the output of one iteration can be both conclusion and renewal, endlessly oscillating between the finite and the infinite.#

Even coffee, as you astutely point out, is not as benign as it seems. Coffee’s stimulant properties sharpen focus and stimulate discourse, which is why its arrival in places like Mocha, Yemen, the Ottoman Empire, and eventually Europe was met with suspicion. In Mocha, coffeehouses became centers of lively debate and intellectual ferment, creating spaces where authority could be questioned. The Ottoman Sultan Murad IV banned coffeehouses, recognizing them as breeding grounds for dissent. Similarly, in England, Charles II issued a proclamation against coffeehouses, alarmed by the political conversations they facilitated. These spaces, energized by coffee, fostered what monarchs and clerics alike feared most: freedom of thought and a return to a kind of polytheistic chaos, where ideas proliferate without central control.

Alcohol, as you note, occupies an ambiguous place in this dynamic. Unlike stimulants or hallucinogens, alcohol numbs rather than expands perception. It can, paradoxically, reinforce monotheistic or monarchical clarity by dulling the mind’s capacity for questioning. This is perhaps why alcohol has often been permitted or even institutionalized within monarchical and religious settings. It sedates rather than destabilizes, making it less likely to disrupt the established order. In contrast, substances like coffee or hallucinogens awaken the mind, inviting new questions and perspectives that challenge the existing framework.

This tension between clarity and perception underlies much of human history. Monotheism, with its singular focus, demands a compression of thought and perception into an orderly system. Substances that open the mind, however, resist this compression, introducing volatility and ambiguity that disrupt stability. Nietzsche’s declaration, “I am dynamite,” resonates here, for it captures the explosive potential of anything that shatters the tyranny of imposed clarity. Whether it’s coffee stirring revolutionary debates in a 17th-century English coffeehouse or DMT opening doors to otherworldly visions, these substances reveal the fragility of systems built on the singularity of perception.

In this light, the historical critique of mind-altering substances is not simply about their physical effects but their metaphysical implications. They threaten the compression of meaning, the consolidation of order, and the stability of authority. The clerics and monarchs who opposed them understood, perhaps intuitively, that these substances reintroduce a kind of polytheism—a multiplicity of perspectives that undermines the singularity they sought to maintain. By stimulating freedom of thought and perception, they dissolve the rigid frameworks of clarity and stability, allowing volatility and ambiguity to reenter the human experience. This is both their danger and their promise.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network fractal

def define_layers():

return {

'World': ['Cosmos-Entropy', 'Planet-Tempered', 'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Generative-Means', 'Cartel-Ends', ], # Polytheism, Olympus, Kingdom

'Perception': ['Perception-Ledger'], # God, Judgement Day, Key

'Agency': ['Open-Nomiddleman', 'Closed-Trusted'], # Evil & Good

'Generative': ['Ratio-Weaponized', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Odds-Monopolized'], # Dynamics, Compromises

'Physical': ['Volatile-Revolutionary', 'Unveiled-Resentment', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Stable-Conservative'] # Values

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Perception-Ledger'],

'paleturquoise': ['Cartel-Ends', 'Closed-Trusted', 'Odds-Monopolized', 'Stable-Conservative'],

'lightgreen': ['Generative-Means', 'Competition-Tokenized', 'Exuberant-Jubilee', 'Freedom-Dance in Chains', 'Unveiled-Resentment'],

'lightsalmon': [

'Life-Needs', 'Ecosystem-Costs', 'Open-Nomiddleman', # Ecosystem = Red Queen = Prometheus = Sacrifice

'Ratio-Weaponized', 'Volatile-Revolutionary'

],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Calculate positions for nodes

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Add nodes and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

G.add_node(node, layer=layer_name)

pos[node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray')) # Default color fallback

# Add edges (automated for consecutive layers)

layer_names = list(layers.keys())

for i in range(len(layer_names) - 1):

source_layer, target_layer = layer_names[i], layer_names[i + 1]

for source in layers[source_layer]:

for target in layers[target_layer]:

G.add_edge(source, target)

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors, edge_color='gray',

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Inversion as Transformation", fontsize=15)

plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 22 Vet Advised When to Sell Horse. Right after an outstanding performance. Because you want to control how its perceived, the narrative backstory, and how its future performance might be imputed. Otherwise, reality manifests with point and interval estimates. This is the subject matter of the opening dialogue in Miller’s Crossing.#