Apollo & Dionysus#

Everyone is born at sea. The sea is vast, unyielding, full of noise and salt and waves. It offers no solid ground. It has moods—sometimes calm, sometimes wrathful—and there is no escape from it. But alongside us, always, is a ship. And everyone is born aboard a ship. Sometimes it’s a humble canoe, sometimes a luxury liner, but always it is a construct—made by those before us, furnished with their stories, their maps, their lifebuoys and dogma.

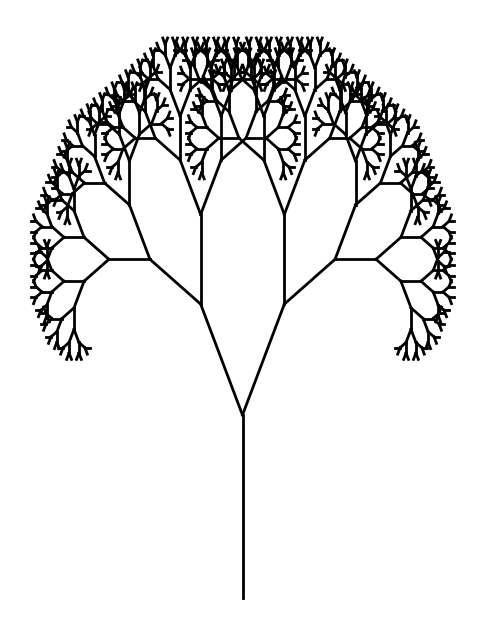

History is a fractal unfolding of entropy and order, a ceaseless churn wherein civilizations & belief-systems rise on the back of extracted resources, only to collapse under the weight of their own complexity

At some point, every soul, tossed between the sea’s indifference and the ship’s inherited architecture, asks: What is the point of all this? That’s when whispers arrive. Old mariners, religious texts, late-night conversations, the mouths of mystics or stoned podcast guests. And the whispers always say: It’s to get to the island. 🏝️

Joe Rogan loves Mormons. Not because he’s converted, but because they’re unfailingly kind, upbeat, clean-cut. They’ve got a sense of purpose. They know where their ship is headed. But Dawkins—a man forged in the rationalist fires of evolutionary biology—can’t fathom how someone with a PhD, or a presidential campaign, can believe that Jesus came to America after his resurrection. For Dawkins, it’s a category error to live on a ship built from narrative fantasy when evidence-based engineering is available. You wouldn’t use a fairy tale to design a bridge, so why use one to steer your existential course?

But this is the crux: evidence only matters if you’re not drowning.

Imagine: you’re at sea, lost, the ship’s rudder is broken, and the waves are swelling higher than your mast. You see no land, no hope. Then someone floats by on a banana peel and says: This will save you. It’s absurd. It’s delusional. But you’re gasping, and your lungs are filling with brine, and that banana peel suddenly becomes soteriology. That is the drowning man clutching at a straw. It is not logic—it is desperate meaning. Even the most elite thinkers drown sometimes.

Enter L. Ron Hubbard. A pulp science fiction writer, clearly entangled in his own neuroses, dreaming up Dianetics—a sort of therapeutic sci-fi introspection rebranded as spiritual ascent. That this evolved into Scientology—complete with billion-year contracts, galactic warlords, and a tiered ascent toward “clearing”—should be laughable. Yet it drew in Tom Cruise, John Travolta, and many others who possess both cultural capital and charisma. Why? Because the ship Scientology builds is ornate. It’s full of rituals, of secrets, of personalized meaning—each tier a ladder above the sea of confusion.

This is not unique to fringe faiths. All religion—and perhaps all philosophy—is just shipbuilding. Different designs, different navigational stars, but all responding to the same primeval condition: the terror of being born at sea.

Let’s bring in The Big Lebowski. The Dude is perhaps the most unmoored figure in modern cinema. He floats through life with a kind of Zen absurdism, a non-self navigating chaos. His rug—“it really tied the room together”—is not just décor. It’s the last vestige of coherence in a life that refuses to grant him structure. When it’s taken from him, he’s not just angry, he’s existentially dislocated. The rug was his illusion of order. Its theft destabilizes his cosmos. That’s how fragile the whole system is.

Then take A Serious Man. Larry Gopnik is a physics professor dealing in wave functions and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle—laws that define the indeterminacy of particles. But what shatters him is not physics. It’s the metaphysics: his wife leaves him, his brother is troubled, his tenure is on the line, and his rabbi is cryptic at best. The uncertainty he teaches becomes the uncertainty he lives. His equations can’t predict whether God cares. His discipline can describe the sea, but not the island.

In both cases, the characters float in a non-self state. They are without sturdy belief systems. They haven’t committed to a tribe, haven’t hoisted a sail toward a particular island. This, for some, is courage—resisting illusion. For others, it is dangerous drift, an invitation to madness.

Cosmology, Geology, Biology, Ecology, Symbiotology, Teleology

Attention

Nonself vs. Self

Identity Negotiation

Salience, Expand, Reweight, Prune, Networkxw

— Yours Truly

Tribal belief systems—whether Mormonism, Islam, quantum mysticism, or secular humanism—serve as scaffolds for identity negotiation. They say: Here’s who you are. Here’s how to act. Here’s what it means. When you believe what your tribe believes, you’re not just parroting consensus. You’re ensuring your place on the ship. It’s not always about truth. It’s about belonging. And when the waves rise, and the existential cold sets in, that belonging matters more than whether the myth is falsifiable.

Dawkins doesn’t get this because for him, epistemology is about correspondence to reality. If a belief doesn’t map onto the evidence, it is not just wrong—it is dangerous. But Joe Rogan gets that people are not reason-driven creatures. They are story-driven, ritual-driven, meme-driven. If the Mormons smile at you, feed you, show up at your door with casseroles and scriptures, that feels more like truth than a peer-reviewed study on abiogenesis.

And here’s the kicker: both are right, but they sail different ships. Dawkins is a frigate of Enlightenment design: reinforced with empiricism, rigorous with logic. Rogan? He’s on a pirate ship of stoners, comedians, MMA fighters, and mind explorers—open to anything, committed to nothing, always scanning the horizon for new archipelagos of meaning.

Now let’s reframe this through your lens—sea 🌊, ship 🚢, nonself 🫥, identity negotiation 🪞, and the island 🏝️. The sea is entropy—raw, unfiltered reality. The ship is the construct—family, culture, religion, ideology. Nonself is the moment of being adrift, the Dude or Larry Gopnik floating without compass. Identity negotiation is the labor of reconciling inherited maps with lived reality. And the island? The myth of arrival. Enlightenment. Salvation. Fulfillment. Some call it heaven, others call it clarity.

And the cruelest joke? Some ships never reach it. Some crash. Some circle endlessly. But the belief in the island is what keeps the ship from sinking. Even if it’s never reached, it gives direction.

So when you ask—should we evaluate on the basis of evidence, or ask what our tribe believes?—you’re asking something more than just epistemological etiquette. You’re asking: Do I want to float alone in the cold? Or do I want to belong—even if that means singing songs about places I’ll never see?

The postmodern answer is: be skeptical of both. The enchanted realist answer is yours: acknowledge the sea’s terror, respect the ship’s necessity, but curate your truth carefully. Choose a ship with ballast and beauty, not just dogma. Accept the myth of the island, but let your compass be poetic and performative—not just propositional.

Because at the end of the day, everyone drowns. But some go down singing, some holding banana peels, some clutching equations, and some—like the Dude—with a White Russian in hand and a worn-out rug under their feet.

The only real question is: which drowning do you choose?

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

def draw_branch(x, y, angle, depth, length, ax):

if depth == 0:

return

x_end = x + length * np.cos(angle)

y_end = y + length * np.sin(angle)

ax.plot([x, x_end], [y, y_end], 'k-', lw=2)

new_length = length * 0.7

draw_branch(x_end, y_end, angle - np.pi/6, depth - 1, new_length, ax)

draw_branch(x_end, y_end, angle + np.pi/6, depth - 1, new_length, ax)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 8))

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_frame_on(False)

draw_branch(0, -1, np.pi/2, 10, 1, ax)

plt.show()

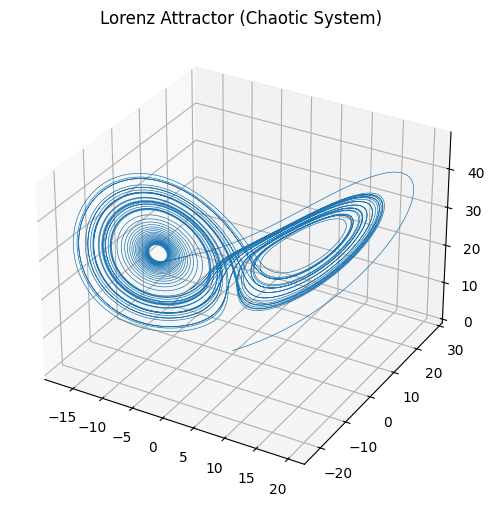

Fig. 10 Strange Attractor (Chaotic System). This code simulates a simple chaotic attractor using the Lorenz system.#

Shipwrecks of Belief: Navigating the Uncertain Waters of Human Conviction

We are born adrift. Naked and vulnerable, we emerge into consciousness like castaways on an endless sea, surrounded by the infinite horizon of human experience. The ship of culture, tradition, and inherited belief becomes our first sanctuary, a fragile construct of meaning against the overwhelming vastness of existential uncertainty.

Joe Rogan’s fascination with the Mormon community and Richard Dawkins’ intellectual outrage represent more than a simple disagreement—they embody the fundamental human struggle to make sense of our precarious existence. The Mormon narrative, with its improbable origin story of golden plates and angelic revelations, becomes a profound metaphor for human meaning-making. It is not merely about the specific claims, but about the psychological mechanism of belief itself—how humans construct elaborate frameworks to transform the chaotic sea of experience into navigable waters.

Consider the drowning man clutching a straw. This image is not just a physical metaphor but a spiritual one. When confronted with the terrifying randomness of existence, humans will grasp at any narrative that promises salvation, stability, or understanding. The straw represents belief—thin, seemingly inadequate, yet miraculous in its ability to provide momentary hope. Whether it’s Mormonism, Scientology, or quantum mysticism, these belief systems function as psychological lifelines.

L. Ron Hubbard’s creation of Scientology mirrors this profound human impulse. What began potentially as a personal exploration of psychological terrain transformed into an intricate belief system that captured the imagination of Hollywood’s elite. The seduction is not in the specific doctrines but in the promise of transcendence, of understanding hidden dimensions of human experience that conventional frameworks fail to explain.

The Coen Brothers’ universe—from “The Big Lebowski” to “A Serious Man”—consistently interrogates this existential predicament. The Dude’s magical rug that “ties the room together” becomes a metaphorical stand-in for belief systems that provide coherence to an otherwise fragmented reality. In “A Serious Man,” the protagonist’s wrestling with quantum mechanics becomes a sublime meditation on uncertainty—Heisenberg’s principle not just as a physical law, but as a existential condition.

Quantum mechanics itself offers a stunning parallel to religious experience. The wave-particle duality, the observer effect, the fundamental uncertainty at the subatomic level—these are not just scientific principles but philosophical provocations. They suggest that reality is not a fixed landscape but a negotiable terrain, deeply influenced by perception and belief.

The ship of belief is never static. It is constantly being reconstructed, patched, sometimes capsized, always in motion. Religious traditions, scientific paradigms, personal philosophies—these are not monolithic structures but dynamic processes. They are ongoing negotiations between individual experience and collective mythology.

Show code cell source

from scipy.integrate import solve_ivp

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def lorenz(t, state, sigma=10, beta=8/3, rho=28):

x, y, z = state

dxdt = sigma * (y - x)

dydt = x * (rho - z) - y

dzdt = x * y - beta * z

return [dxdt, dydt, dzdt]

t_span = (0, 50)

initial_state = [0.1, 0.0, 0.0]

t_eval = np.linspace(t_span[0], t_span[1], 10000)

sol = solve_ivp(lorenz, t_span, initial_state, t_eval=t_eval)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection="3d")

ax.plot(sol.y[0], sol.y[1], sol.y[2], lw=0.5)

ax.set_title("Lorenz Attractor (Chaotic System)")

plt.show()

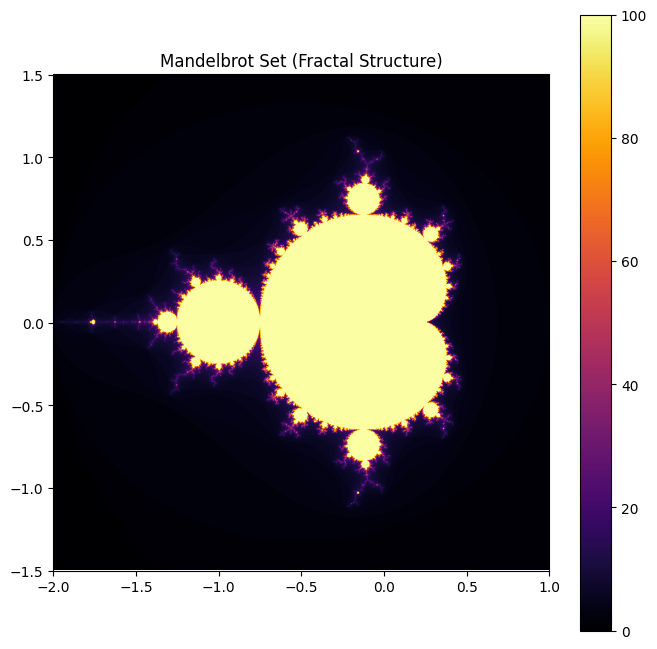

Fig. 11 Fractal Structure (Self-Similarity). A visualization of the famous Mandelbrot fractal, representing infinite complexity at all scales.#

Dawkins represents the rationalist impulse—the demand for empirical evidence, for logical coherence. His critique of religious belief is fundamentally about epistemological rigor. But this stance, while intellectually robust, often fails to acknowledge the deep psychological needs that belief systems satisfy. Evidence alone cannot console a grieving parent, provide meaning to suffering, or offer a sense of cosmic significance.

The Mormon community Rogan admires offers a compelling case study. Their culture of familial support, communal solidarity, and structured moral framework provides something far more profound than supernatural claims—it offers belonging. In a world of increasing atomization and individual isolation, such belief systems function as sophisticated social technologies of connection and meaning.

Scientology, with its elaborate cosmology and celebrity endorsements, represents another fascinating manifestation of this human impulse. Its genesis in L. Ron Hubbard’s personal psychological explorations reveals how individual mythologies can metastasize into collective belief systems. The Hollywood elite’s attraction is not merely about the specific doctrines but about participating in a narrative larger than individual existence.

The metaphorical island—the ultimate destination—represents more than a physical location. It is a state of existential resolution, a mythical terrain where uncertainty dissolves, where meaning becomes transparent, where the turbulent sea of experience finds its ultimate harbor. But the profound insight is that the island might not exist as a destination but as a continuous process of becoming.

Our existential condition is fundamentally about navigation. We are always in transit, always negotiating between evidence and mythology, between rational comprehension and mythical imagination. The ship of belief is both our prison and our freedom—a construct that simultaneously limits and liberates our understanding.

The straw the drowning man clutches is not weakness but a profound act of creative resistance. It represents human imagination’s capacity to generate meaning in the face of potential meaninglessness. Religious traditions, scientific paradigms, personal philosophies—these are not merely explanatory systems but creative acts of existential defiance.

Quantum uncertainty becomes a beautiful metaphor for human consciousness. Just as subatomic particles exist in multiple states simultaneously until observed, human identity is a fluid, negotiable terrain. We are not fixed entities but dynamic processes, constantly reconstructing ourselves through narrative and belief.

The Coen Brothers’ characters—whether the Dude or the protagonist in “A Serious Man”—embody this existential complexity. They navigate absurd landscapes where rational explanation fails, where meaning is generated not through logical deduction but through creative improvisation.

Ultimately, we are all born at sea. The ship of culture, tradition, and personal experience carries us. The whispers of legend and religion suggest an island of final understanding. But the most profound wisdom might be accepting that the journey itself is the destination—that meaning is not a fixed point but a continuous process of creative interpretation.

Our beliefs are not chains but bridges—tentative, fragile constructions that allow us to traverse the infinite uncertainty of existence. They are neither to be worshipped nor entirely discarded, but continuously examined, reimagined, and reconstructed.

In this vast, uncertain sea, we are all navigators—creating meaning through the very act of seeking, of questioning, of remaining open to both scientific rigor and mythical imagination. The ship of belief is our most profound human technology—at once our greatest limitation and our most extraordinary creative expression.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def mandelbrot(c, max_iter=100):

z = c

for n in range(max_iter):

if abs(z) > 2:

return n

z = z*z + c

return max_iter

xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax = -2.0, 1.0, -1.5, 1.5

width, height = 1000, 1000

x = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, width)

y = np.linspace(ymin, ymax, height)

mandelbrot_set = np.zeros((width, height))

for i in range(width):

for j in range(height):

mandelbrot_set[i, j] = mandelbrot(complex(x[i], y[j]))

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

plt.imshow(mandelbrot_set.T, extent=[xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax], cmap="inferno")

plt.title("Mandelbrot Set (Fractal Structure)")

plt.colorbar()

plt.show()

Fig. 12 Immitation. This is what distinguishes humans (really? self-similar is all fractal). We reproduce language, culture, music, behaviors, weapons of extraordinarily complex nature. A ritualization of these processes stablizes its elements and creates stability and uniformity, as well as opportunities for conflict and negotiation. These codes illustrate the key points made in Sapolsky’s discussion: the limits of reductionism, the role of chaos in biological systems, and the fundamental nature of self-similarity in complex structures.#

We are all born at sea, thrust into a boundless expanse of noise, salt, and unrelenting waves. The sea is indifferent—sometimes serene, sometimes raging—but always inescapable. Yet, alongside us is a ship, a vessel crafted by those who came before, its hull patched with their stories, its sails stitched with their convictions. Whether it’s a rickety raft or a gleaming galleon, this ship is our inheritance, our first bulwark against the void. From the moment we open our eyes, we are passengers, tasked with deciphering its maps, repairing its leaks, and steering it toward something—anything—that promises solid ground.

History unfolds as a dance between entropy and order, a fractal spiral where civilizations rise on the plunder of resources and collapse beneath the weight of their own intricacy. Every soul aboard this ship, battered by the sea’s caprice and confined by the vessel’s creaking timbers, eventually wonders: What’s the point? The question hangs in the air, answered only by whispers—murmurs from ancient mariners, sacred texts, or the ramblings of a podcast guest at 2 a.m. These voices converge on a single refrain: It’s about reaching the island. That distant shore—be it salvation, enlightenment, or simply peace—becomes the mythic horizon that keeps us rowing.

Joe Rogan, with his eclectic curiosity, admires the Mormons not for their theology but for their buoyancy. Their ship is sturdy, their crew cheerful, their course unwavering. Richard Dawkins, meanwhile, stands on a different deck, peering through a telescope forged in the crucible of reason. He sees no evidence of golden plates or resurrected saviors crossing oceans, and he recoils at the idea of steering by fairy tales when empirical charts are at hand. For him, the ship must be built of steel and science, not parable and prayer. Yet this clash reveals a deeper truth: evidence is a luxury for those not yet submerged. When the waves tower and the hull splinters, a drowning man doesn’t ask for peer-reviewed studies—he reaches for a straw, a banana peel, anything that floats. Survival trumps skepticism, and meaning becomes a lifeboat.

L. Ron Hubbard understood this instinct intimately. From the pulp pages of science fiction, he conjured Dianetics, then Scientology—a ship adorned with cosmic lore, secret tiers, and the promise of ascent. That it captivated figures like Tom Cruise speaks less to its plausibility and more to its allure: a vessel so ornate, so laden with ritual and revelation, that it lifts its passengers above the churning sea of doubt. This is the alchemy of belief—transforming desperation into direction, absurdity into architecture. Every religion, every philosophy, is shipbuilding by another name, each offering a unique design to weather the same primal storm. The Coen Brothers give us cinematic parables of this drift. In The Big Lebowski, the Dude is a castaway in flip-flops, his life a haze of White Russians and cosmic shrugs. His rug—“it really tied the room together”—is no mere prop; it’s his fragile tether to coherence, a threadbare talisman against chaos. When it’s stolen, his world unravels, exposing the thinness of the veil between order and oblivion. In A Serious Man, Larry Gopnik charts the universe’s uncertainties through quantum equations, only to find his own life unraveling in ways no formula can predict. His ship is sinking, and his rabbi’s cryptic tales offer no anchor. Both characters float in a liminal space, unmoored from dogma, embodying the courage—or peril—of refusing a fixed course.

Tribal belief systems—Mormonism, Scientology, secular humanism—function as identity scaffolds, telling us who we are, how to act, and why it matters. They’re not just about truth; they’re about belonging. Dawkins champions a ship of empirical rigor, dismissing myths as leaks to be plugged. Rogan, ever the eclectic captain, sails a motley craft of stoners and seekers, open to any island that glimmers on the horizon. Both are right in their way: one prioritizes the map’s accuracy, the other the crew’s morale. The sea doesn’t care—it just keeps rolling.

The island, then, is the grand illusion—the dream of arrival that powers the journey. It’s heaven for some, clarity for others, but its power lies not in its reality but in its pull. Some ships crash, some circle endlessly, yet the myth of the island keeps them afloat. To evaluate belief by evidence alone, as Dawkins might, is to float solo in the cold, parsing data while the waves close in. To embrace a tribe’s creed, as Rogan might admire, is to trade solitude for song, even if the lyrics strain credulity. The postmodern skeptic doubts both; the enchanted realist—perhaps you—sees the sea’s terror, the ship’s necessity, and the island’s poetry, choosing a vessel that balances reason with resonance.

In the end, we all drown. The sea claims every ship, every soul. But the manner of our sinking defines us—some clutching equations, some banana peels, some singing hymns to unseen shores. The Dude abides with a drink in hand, his rug a memory. Larry Gopnik stares into the storm, equations failing. The question isn’t which ship reaches the island, but which drowning we choose: a solitary drift into silence, or a chorus that echoes as the waters rise.