Defensiveness

Introduction

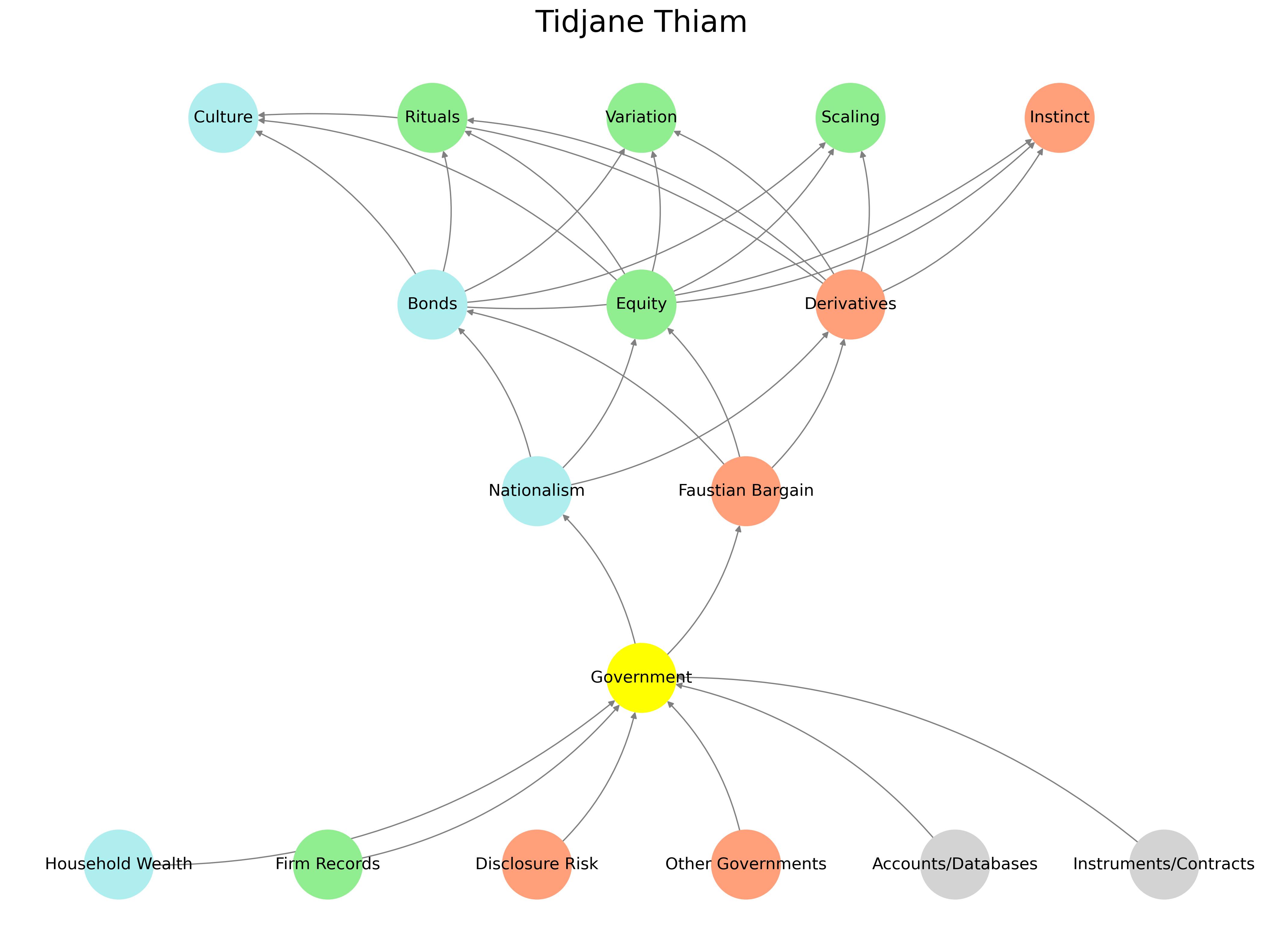

In the unwieldy world of finance, where trust, perception, and informational asymmetry collide like tectonic plates, the accusation of defensiveness can be fatal. When Tidjane Thiam, a towering figure both physically and intellectually, faced Swiss media for the first time as Credit Suisse CEO, his perceived defensiveness undercut his authority. The backlash wasn’t about content—it was about tone. In a culture obsessed with soft power and the appearance of restraint, even mild assertiveness, especially from someone perceived as an outsider, registers as arrogance or, worse, concealment. What was really on trial was not Thiam’s intellect or intent, but his embodiment of “nonself.” The outsider. The foreign body. The immunological threat to a legacy institution with baroque rituals of continuity.[1]

Caption: Credit Suisse headquarters in Zurich, symbolizing institutional legacy. Source: Ukubona Financial Archive.

State and Narrative

Above them hovers the State—Government proper—our second layer. This level is Janus-faced: it both projects authority downward into civic life and absorbs chaotic stimuli from below. It legislates, monetizes, centralizes. But crucially, it doesn’t flourish on its own. It needs narrative. It must make its presence appear necessary rather than oppressive.[3]

Caption: Swiss Parliament, representing state authority and narrative. Source: Ukubona Political Archive.

Nationalism and the Faustian Bargain

And this leads us to the third layer: Nationalism vs. the Faustian Bargain. This is the spiritual pivot. Nationalism is the cry of the self threatened by the other. The Faustian bargain, meanwhile, is the elite's quiet surrender of sovereignty in exchange for power—often through finance, global integration, or shadow alliances. Both are defenses. One is loud and populist; the other is subtle and technocratic. Both represent responses to the nonself.[4]

Derivatives and Cognitive Finance

The fourth layer is the deepest gamble: Derivatives, Obfuscation, Bluff, Emergence. This is where finance mimics cognition. Derivatives are to assets what dreams are to experiences: abstracted, traded, and re-encoded in symbols. Obfuscation is not a bug here but a feature. Bluff is strategy; emergence is pattern recognition after the fact. This is the cognitive cortex of the system—the layer where high-frequency trading, regulatory arbitrage, and secrecy laws (hello Switzerland) live. And Thiam, coming from Prudential and Côte d'Ivoire by way of McKinsey, was seen as a master of this terrain—and thus a threat to its unspoken rules.[5]

Caption: Video explaining financial derivatives, highlighting cognitive complexity. Source: Ukubona Financial Archive.

Rituals and Cultural Scaling

But no system lasts without a cultural wrapper. The fifth layer—Rituals, Variations, Scaling, Culture—is not decorative. It is constitutive. The same rituals that animate Indigenous knowledge systems (rites of passage, sacred meals, repeated proverbs) operate in global finance as earnings calls, dress codes, and deal rituals. Variation matters too—Subprime mortgages in the U.S., covered bonds in Germany, property bubbles in Australia. The scaling logic is consistent: local deviation, global resonance. And here lies the bitter paradox for someone like Thiam. He represented scale—Black, global, educated, elite—and yet his very scale made him vulnerable to rituals of suspicion, exclusion, and blame. He was hired, in many ways, to fail—because success would have upended too many rituals too quickly.[6]

Caption: Earnings call setup, illustrating financial rituals. Source: Ukubona Cultural Archive.

Neural Signals and Trust

This five-layer system is not just a financial schema—it is a neural one. Defensive behavior is not a flaw in leadership; it is a signal, a spike in the data. Like a neuron firing under duress, defensiveness reveals a breach in narrative coherence. The public—like the brain—interprets this not as honesty, but as danger. Trust falters. Culture reasserts itself. The system returns to baseline—safe, slow death over volatile transformation.[7]

Conclusion

Thiam’s story, then, is not merely about Credit Suisse or even about race and globalism. It is about what systems do to signals that arrive too sharply, too fast, from outside. Whether in immunology, epistemology, or finance, the pattern holds: the nonself must be neutralized unless it can be ritualized. And ritual takes time. Variation takes risk. Scaling requires loss. What’s left, then, is this: every C-suite, every government, every node in our newly redrawn network is constantly balancing the pressure to explain with the need to remain silent. To signal competence without appearing reactive. To remain sovereign while being deeply embedded. This is not just a political art—it is cognitive choreography. Ritual. Variation. Bluff. Scaling. And behind it all, the shadow of the Faustian deal: that in choosing to be understood, one may lose the power to be believed.

“In choosing to be understood, one may lose the power to be believed.”

See Also

Acknowledgments

- Muzaale, Abimereki. Ukubona: Neural Fractals of Being. Ukubona Press, 2024. [↩︎]

- Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Penguin, 2006. [↩︎]

- Nestle, Marion. Food Politics. University of California Press, 2013. [↩︎]

- Katz, Sandor. The Art of Fermentation. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2012. [↩︎]

- Bittman, Mark. How to Cook Everything. Wiley, 2008. [↩︎]

- Berry, Wendell. The Unsettling of America. Sierra Club Books, 1977. [↩︎]

- USDA. FoodData Central. United States Department of Agriculture, 2025. [↩︎]