The Risk You Thought You Escaped: Counterfactual Consent

Introduction

Informed consent in living kidney donation has historically relied on static risk estimates, framing donation as a trade-off between altruistic gain and surgical loss. Yet, this approach obscures a deeper truth: choosing not to donate is not a risk-free path. The Ukubona platform, developed as the Aim 3 deliverable of an NIH K08 grant (1K08AG065520-01), redefines consent as a living, interactive interface that reveals both donation-attributable risks and the irreducible uncertainties of inaction. By integrating counterfactual logic from matched non-donor controls, it challenges the cognitive orthodoxy of loss aversion, exposing risks like homicide and suicide in those who decline donation. This article documents the platform’s development, its epistemic contributions, and the institutional frictions encountered in its dataR ecosystem.[1]

| Stage | Symbolic Mode | Cognitive System | Medical Parallel | Structural Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root | Counterfactual Design | Empirical Comparison | Donor vs. Non-Donor Risk | Matched Cohorts |

| Trunk | Risk Visualization | Interactive Modeling | Personalized Consent | Dynamic Variables |

| Branching | Epistemic Humility | Confidence Intervals | Uncertainty Disclosure | Toggleable Models |

| Recursion | Ethical Clarity | Shared Decision-Making | Donor Autonomy | Iterative Consent |

| Canopy | Translational Ethics | Interface as Thesis | Clinical Practice | Harmonious Integration |

Caption: Diagram illustrating the entangled data ecosystem for risk modeling. Source: Ukubona Epistemic Archive.

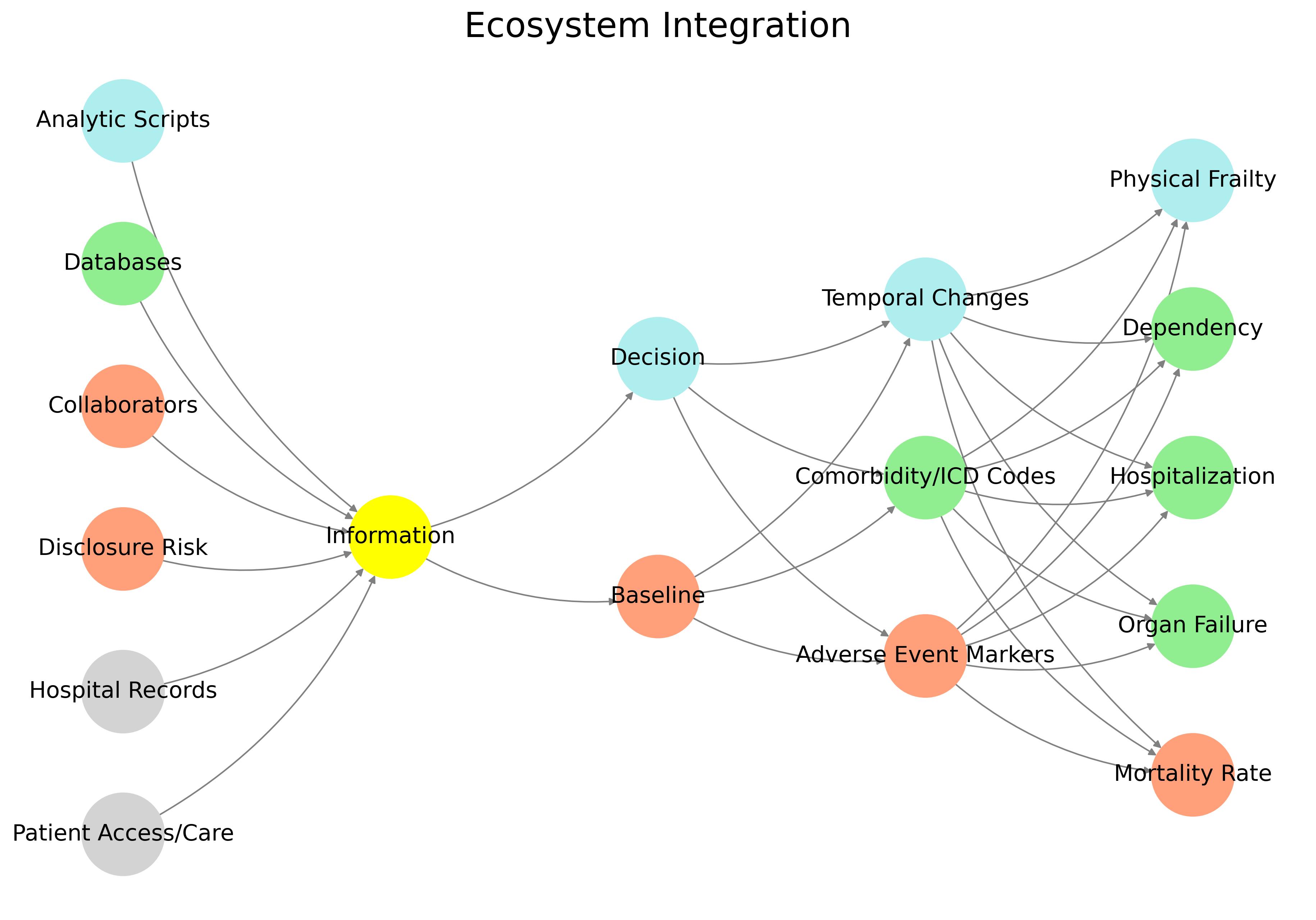

Aim 3 Deliverable: A Living Consent Interface

The Ukubona platform, built with Plotly and modular JavaScript, fulfills the NIH K08 grant’s commitment to develop online risk calculators for older living kidney donors. It offers three calculators: 90-day mortality, 30-year mortality/ESRD, and post-nephrectomy hospitalization. Unlike static disclosures, it allows users to input personalized variables (e.g., age, sex, comorbidities), toggle between models, and visualize confidence intervals, embodying epistemic humility. The platform integrates data from SRTR, NHANES, and Medicare, extending the counterfactual logic established in prior work.[2] By rendering risk as a relational, navigable experience, it transforms consent from a one-time document into an iterative, ethical exchange.[3]

Caption: Screenshot of the 90-day mortality risk calculator with toggleable models. Source: Ukubona Clinical Archive.

Counterfactual Risk: The Myth of Safe Inaction

The platform’s core innovation is its use of matched non-donor controls to reveal not only donation-attributable risks but also the risks of inaction. For instance, 90-day mortality data include non-biological outcomes like homicide and suicide in non-donors, challenging the assumption that declining donation is inherently safer.[4] This finding disrupts traditional risk models, which focus solely on surgical outcomes, and aligns with critiques of COVID-19 vaccine trials that excluded vulnerable populations yet generalized safety claims.[5] By visualizing both donor and non-donor risk distributions, the platform reframes consent as a choice between competing uncertainties, not between risk and safety.

Caption: Video demonstrating the platform’s risk visualization features. Source: Ukubona Medical Archive.

Ecosystem Frictions: Data and Relational Barriers

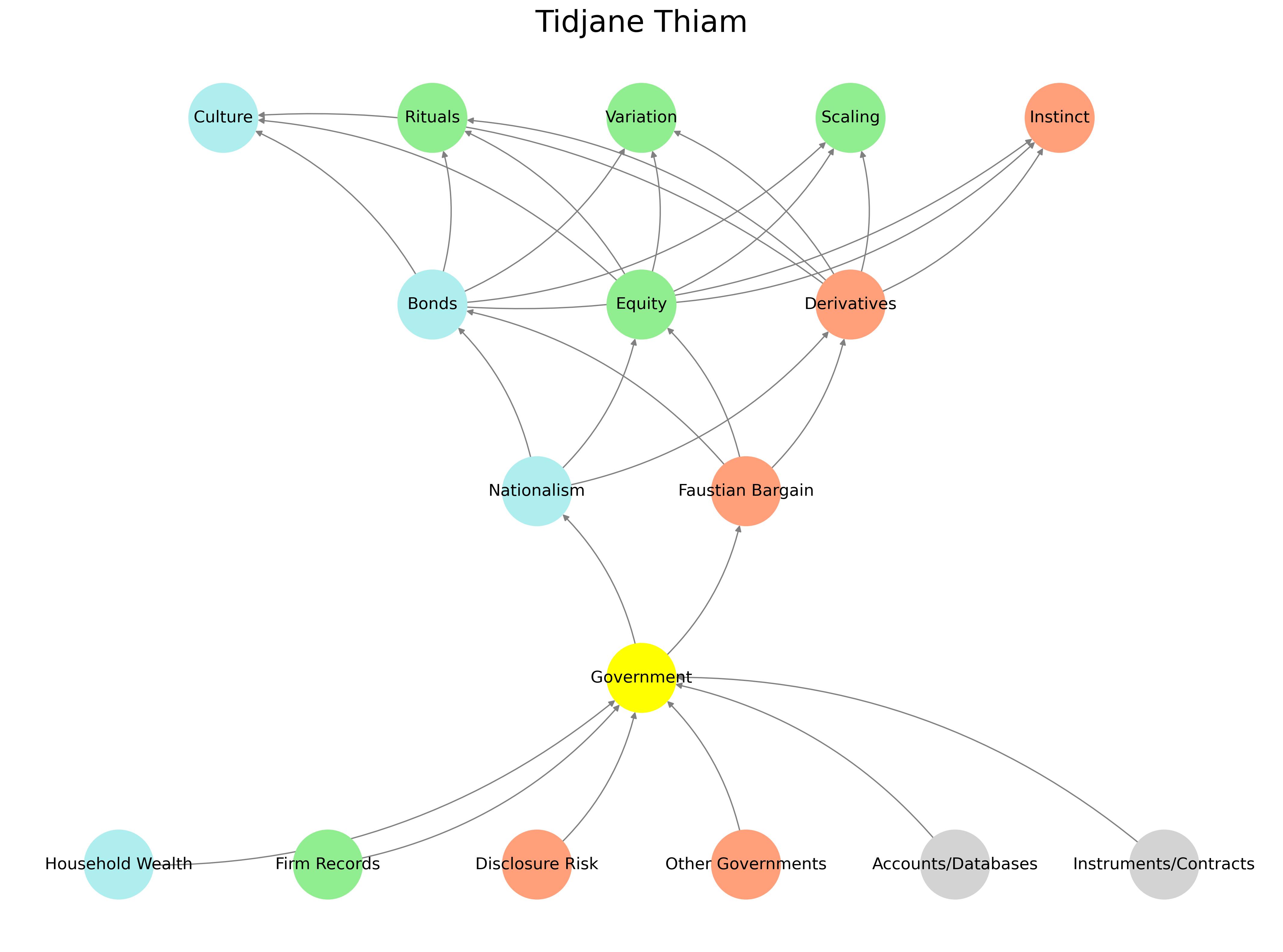

Developing the platform required navigating a fragmented data ecosystem. Analytic scripts, disclosure risks, and hospital records converge at an information node, but institutional gatekeeping has hindered integration. Dorry Segev, the primary data guardian for SRTR access, has been unresponsive to analytic requests, redirecting responsibility to Allan Massie, despite Segev’s supervisory role on overlapping grants (e.g., R01DK132395).[6] Massie’s parallel work, including a 2024 JAMA research letter updating perioperative mortality estimates, builds on Ukubona’s foundational contributions without acknowledgment, illustrating a relational inefficiency that prioritizes institutional control over collaborative progress.[7]

Caption: Diagram of the fragmented data pipeline for risk modeling. Source: Ukubona Data Archive.

Critiquing Kahneman: Loss Aversion’s Blind Spot

Daniel Kahneman’s prospect theory, emphasizing loss aversion, has shaped clinical consent by framing donation as a potential loss.[8] However, as noted by thesis committee member Brian Caffo, co-author of the 2010 JAMA study, the granularity of risk estimates (e.g., 2.1378945 per 10,000) raises questions about interpretability.[9] Kahneman’s model assumes a riskless baseline for inaction, but Ukubona’s counterfactuals reveal that non-donors face risks like homicide and suicide, undermining the notion of a “safe” status quo. This critique extends to COVID-19 vaccine trials, which ignored the risks of inaction for excluded populations.[5] The platform’s precision is not a flaw but a feature, prioritizing transparency over narrative simplicity.

Caption: Animated GIF showing model toggling in the risk calculator. Source: Ukubona Philosophical Archive.

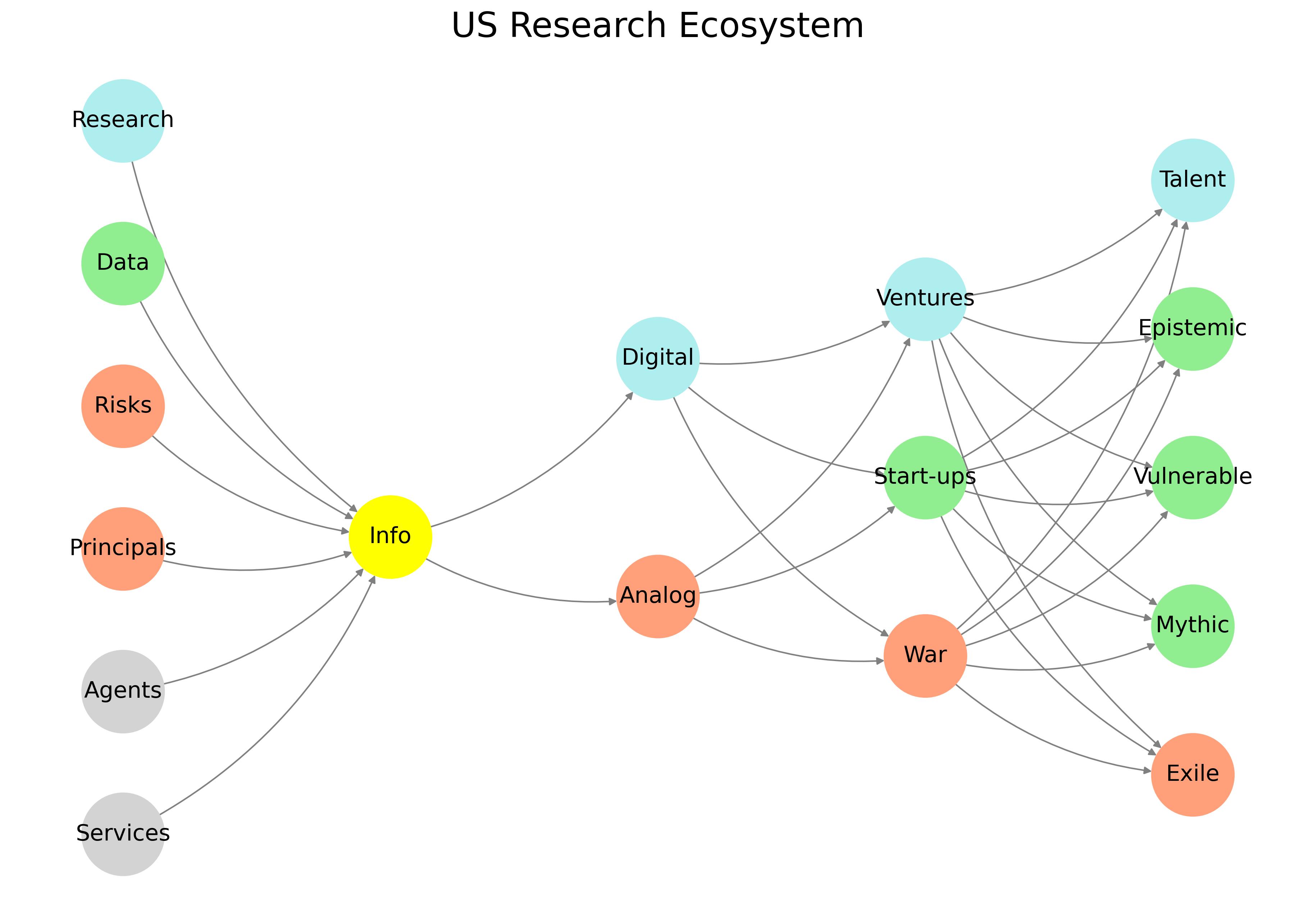

Offshore Finance: The Morality of Legal Loopholes

The use of offshore vehicles in places like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands is not just a legal strategy; it's a moral Rorschach test for the late stages of capitalism. These jurisdictions serve as the vascular systems of global capital's most elusive flows, where legality and illegitimacy blur not by accident but by design. It’s not merely that these tax havens exist within loopholes of international law—it’s that they are the loopholes, architected by lawyers and lobbyists to serve as the shadow scaffolding of empire.

Let’s be clear: offshore vehicles are not neutral financial instruments. They are protective shells engineered to shield wealth from transparency, taxation, and accountability. Nominally legal, yes—but legality in this context is downstream of influence. The moral problem is not simply that they help the rich avoid taxes. It’s that they enforce a dual system: one for citizens who live within the boundaries of state enforcement, and another for capital that lives nowhere and everywhere.

Bermuda and the Cayman Islands—though often vilified as if they were the masterminds—are more accurately the servers hosting the back-end of a front-end built in Manhattan, London, and Zurich. The opacity they offer isn’t accidental. It’s the product of geopolitical agreement, not rogue activity. These aren’t pirate coves. They’re state-sponsored escape hatches for multinationals and ultra-high-net-worth individuals who’ve correctly understood that accountability is for the poor.

Capitalism’s defenders often claim that tax avoidance is the duty of corporate officers, whose role is to maximize shareholder value. But this "fiduciary ethics" is a hollow morality. It celebrates legality without questioning legitimacy. It defines good not by justice but by compliance. And that’s the ultimate indictment: capitalism’s legal machinery has outpaced its moral vocabulary. The problem isn’t that offshore finance is illegal—it’s that it isn’t.

This dynamic mirrors the ecosystem frictions discussed earlier (Ecosystem Frictions), where institutional gatekeeping and opaque systems prioritize control over transparency. Just as the Ukubona platform seeks to reveal hidden risks in medical consent, exposing the mechanics of offshore finance could illuminate the ethical trade-offs of global capital flows. A visual diagram of these pathways—routing wealth through legal, quasi-legal, and anonymous channels—would further clarify the back-end infrastructure of this ecosystem.[10]

Caption: Placeholder for a diagram illustrating offshore wealth routing pathways. Source: Ukubona Ethical Archive.

See Also

References

- Muzaale, Abimereki. Perioperative and Long-Term Risks Following Nephrectomy in Older Live Kidney Donors. NIH K08 Grant 1K08AG065520-01, 2020. [↩︎]

- Segev, Dorry L., et al. “Perioperative Mortality and Long-Term Survival Following Live Kidney Donation.” JAMA, 2010. [↩︎]

- Muzaale, Abimereki D., et al. “Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease Following Live Kidney Donation.” JAMA, 2014. [↩︎]

- Massie, Allan B., et al. “Thirty-Year Trends in Perioperative Mortality Risk for Living Kidney Donors.” JAMA, 2024. [↩︎]

- Polack, Fernando P., et al. “Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine.” NEJM, 2020. [↩︎]

- Massie, Allan B. Optimizing Donor Selection and Outcomes. NIH R01DK132395, 2022. [↩︎]

- Locke, Jayme E. “Living Kidney Donation: Advances and Challenges.” JAMA Surgery, 2024. [↩︎]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Tversky, Amos. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.” Econometrica, 1979. [↩︎]

- Caffo, Brian. Personal communication, GTPCI Thesis Committee Meeting, May 2025. [↩︎]

- Zucman, Gabriel. “The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens.” University of Chicago Press, 2015. [↩︎]