4.3#

Definition#

“Open source hardware” (OSH) refers to the design specifications of a physical object that are licenced such that they and the object can be studied, modified, created, and distributed by anyone. Its formal definition [def] was written by the open hardware community back in 2010, and is maintained by the Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA), a US-based non-profit.

Translations of hardware in some languages may bias the concept towards electronics, but with hardware we refer to any physical, tangible object: machines, electronic devices, biomaterials, textiles. You will also often see the terms open hardware and open source hardware used interchangeably in the literature and in this article.

OSH in Research#

In 2016, the Global Open Science Hardware community took the OSHWA definition and tailored it to the specific needs of science:

Open Science Hardware (OscH) refers to any piece of hardware used for scientific investigations that can be obtained, assembled, used, studied, modified, shared, and sold by anyone. This includes standard lab equipment as well as auxiliary materials, such as sensors, biological reagents, analog and digital electronic components.

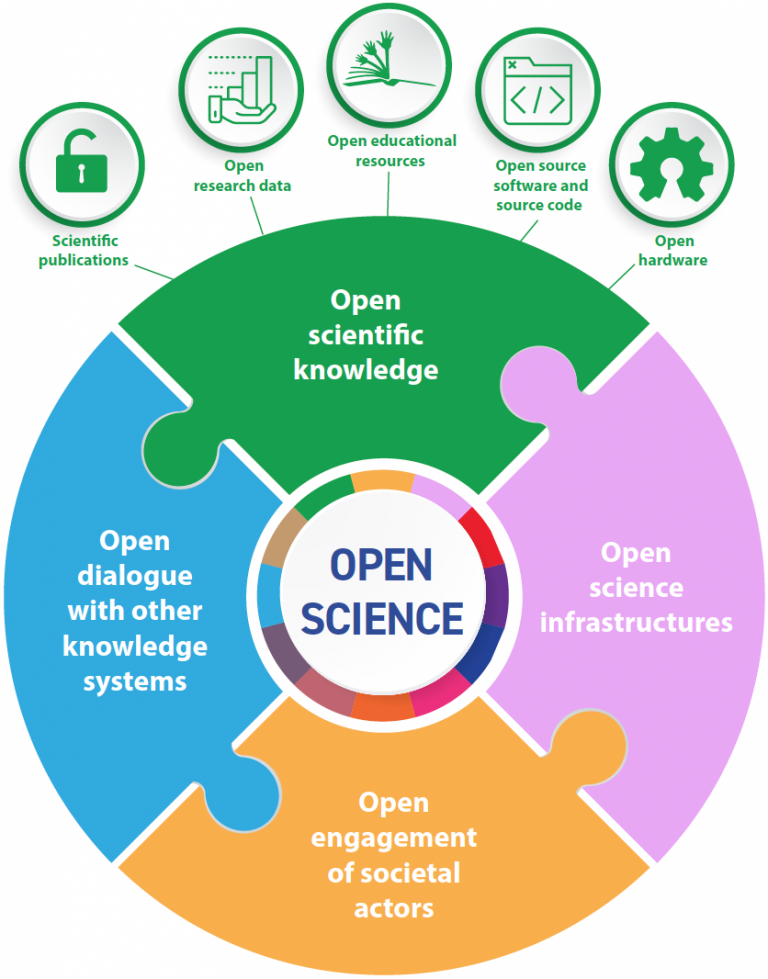

In 2021, the UNESCO Open Science Recommendation became the first policy document to include OSH as a component of open science. The recommendation considers open hardware as a pillar of scientific knowledge that should be open.

What is the source of open source hardware?#

Like open source software, the “source code” for open hardware is available for modification or enhancement by anyone. In contrast to software, where the source is plain text code, the OSH source is more complex. OSH design information refers to: schematics, blueprints, logic designs, Computer Aided Design (CAD) drawings or files, and the like (see Technical documents). It usually entails text, binary files and software.

Importantly, OSH projects should share both raw and derived source files. For instance, 3D object designs should be shared as print-ready files (.stl), but also as modifiable 3D objects (the format of these files will depend on the software used). It is necessary to provide the raw files to enable modification, even if they can often only be opened in proprietary software, and their use requires specific skills. The derived versions are used to build the hardware, but often are not suited for modification. Users with access to the tools that can read and manipulate these raw source files can update and improve the physical device. If they wish, they can proceed to share such modifications.

Although OSH projects are diverse in their degree of “openness”, best practices in OSH guide us to identify a core, minimum documentation that needs to be in place so others can study, modify, distribute, make or sell our hardware. We will go through these various components in the following sections.

Types and phases of open source hardware#

Fig. 6 The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.#

OSH projects emerge as a response to a concrete need, which is reflected in the project lifecycle. For example, you may need to process lots of samples, or to measure a parameter you were not considering before, or to take measurements outside of the lab. With the analyzing of your need, your OSH project starts. It is advisable to scope the project at this point, maybe looking for similar project one can join, instead of starting a new one. It may indeed be useful to draw a roadmap, look and find future users, contributors and manufacturers (who may have complementary skills to yours), and decide for a license. It is reasonable to invest quite a lot of time in looking for similar projects. OSH are often difficult to find and comprehend, but finding projects may save you a lot of time and hassle. Indeed, you may learn a lot about your needs, refine your ideas, and may even find collaborators while browsing existing OSH projects.

You may then test some ideas to address your particular need, which is a process called prototyping.

After many iterations and testing, you will be able to select a prototype for further development.

The design that solves your need but is not yet complete nor ready to be replicated (usually because some parts are not well documented or requires a lot of manual adjustments) is called a demonstrator.

When the design and documentation are polished and are ready to be used by hardware producers, the hardware is usually labeled as a market-ready product.

While many people start generating documentation and share their design online at the demonstrator stage, open science enthusiasts advise being open from the beginning of the description of needs phase.

There are different degrees for how open an OSH project can be [], but every step in this direction is welcome and an opportunity to contribute to better research and open new career paths. Designs that are well-documented and offer a solution to a concrete problem can be easily reused by others. They may replicate your design exactly to test it, or reproduce it to adapt it to their particular need. It is worth thinking about your future self as one of the project collaborators when balancing the resources used in opening and documenting an OSH project, and the resources used to develop the hardware further.

In order to make your project more open, one can work on several aspects of open source, which are outlined in the following sections.

Why should you use or develop open source hardware?#

Fig. 7 The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.#

For you#

People develop and share OSH for a variety of reasons. Particularly in research, OSH provides very concrete advantages:

Flexibility and Speed: You can quickly customize and combine open designs to test new research questions in an accessible way, instead of depending on vendors, their timelines and bureaucracy.

Simplicity: As OSH has a lower price tag than conventional equipment, it is much easier to obtain while bypassing the bureaucracy of contracting vendors.

Control: If a supplier goes out of business, users and/or third party companies have the information to keep systems running.

Visibility: Researchers and engineers developing OSH make their work more visible to more people. They also increase opportunities for networking and impact, especially in projects involving a community.

Education: By using open hardware, researchers pick up new skills and can better understand how a certain tool captures data on specific phenomena/events.

It is worth mentioning here that building and developing OSH may require specific knowledge and skills on one hand, and quite a lot of time, on the other hand. Buying industrial hardware with the corresponding client support these companies offer may be cheaper, especially if you do not have enough technical support in house.

For science#

Quality: To make science, we need research instruments; we also need to build on top of others’ knowledge. A contributor might offer a totally novel solution to a design problem that would never occur to you; contributors may also catch errors that might have been missed.

Reproducibility: OSH designs can be replicated, allowing for verification and reproduction of experiments and data. Moreover, users can have much better control on the calibration of their devices, boosting replicability even further.

Inclusiveness: OSH can make science possible where resources are scarce. Local adaptation and production of OSH helps reducing the impact of import restrictions and bureaucracies that obstaculise science. Also, more students may be able to interact with scientific tools in hands-on sessions, as the equipment is cheaper.

Sustainability: OSH means you have all the information for repairing and maintaining devices locally, extending the lifespan of the product and reducing waste.

Many researchers who develop or use OSH for research also value OSH as an educational tool. Working with OSH designs allows students and researchers to fully understand how a certain tool captures data on specific phenomena/events.

How to make hardware open source#

In order to make your hardware reusable and modifiable by others, its source should be shared with an appropriate license. This is usually done via specific online platforms (see Platforms. The type and amount of shared content depends on the complexity of the OSH, and on the importance of the community aspects of the project.

In the following sections, you can find descriptions of the common types of content that you should consider sharing, such as project documentation, technical documentation, and community interactions. You are not required to post or document them all, but the more you share, the more the community benefits, and the more it can give back.

There is a lot of crossover with files to include in open source software projects (see rr-rdm-metadata-documentation), and the community aspects that are common to any open source project are described elsewhere (see pd-overview-repro)

Project documentation#

Your OSH project should at a minimum provide a license rr-licensing-hardware together with a README file with all the basic, general information a newcomer needs to get oriented. Include a general description of the hardware’s identity and purpose, written as much as possible for a general audience. That is, explain what the project is and what it is for, before you get into the technical details.

On top of what is mentioned in detail in the open source project documentation page (pd-overview-repro) for project plan, people involved, and contribution process, you should specifically think about your audience when writing OSH documentation. Indeed, your project might be reused by people with different skills, roles, objectives, and socio-economic and cultural environments. Because of this it can be useful to create a list of skills that are required to build or use the hardware. Someone trying to build it from scratch, for example, will require specific set of prior knowledge, skills, and tools. A different set is needed to perform maintenance tasks. An end user operating the assembled project might require an entirely distinct skillset (and documentation).

Take particular care about safety instructions. OSH makers are not always formally trained engineers and may not be able to easily differentiate between dangerous and safe manipulations.

Your project documentation may also include a functional overview of the project’s parts or modules, as well as a short description of the software needed to use the hardware. Also give an overview of the state of the hardware, software and documentation (current state, ongoing development, and/or any future plans for the project), and other information you think may be useful for newcomers.

Technical documents#

Technical documents provide the source needed to study and replicate a hardware design. In contrast to project documentation and community building, technical documents for OSH are quite specific, but can be considered analogous to what source code is for software. Depending on the project, technical documents may include technical drawings, images describing electronic schematics, computer-aided design (CAD) files, or assembly instructions to replicate the design. A thoroughly documented project will have all types of documents. It may also include code (firmware and software) necessary to run the hardware. The source files (like CAD files) are best accompanied by textual and multi-medial documentation, such as guides for manufacturing, assembly, maintenance, and development.

We provide here a quite exhaustive list of documentation elements. Your project may not need all of them, but it is worth considering having at least minimal information for most of these elements:

A context description which may reflect project maturity, complexity, the intentions of authors on how it should be used, and technical specifications. It may include standards compliance (the DIN-SPEC standard for instance) and an estimation of the overall budget required and build time.

A Bill of Materials (BOM): A list or spreadsheet describing part numbers, putative suppliers, costs, and a short description. Make it easy to tell which item in the bill of materials corresponds to which component in your design files: use matching reference designators in both places, provide a diagram indicating which part goes where, or otherwise explain the correspondence.

Assembly instructions. To help others make and modify your hardware design, you should provide instructions for going from your design files to the working physical hardware. It is good to publish annotated photographs (or video) from multiple viewpoints and at various stages of assembly. If you do not have photos, posting annotated 3D renderings of your design is a good alternative. Either way, it is good to provide captions or text that explain what is shown in each image and why it is useful.

Manufacturing instructions: The manufacturing process of parts that have been made for this project should be documented as well. This is specially important if they are available for purchase from only a handful of small/medium businesses.

A list of required tools and associated settings, for both the software used for development and the machine tools for replication.

Design files with parts metadata, typically including the manufacturing process, the materials with dimensions, mass, and units. A functional overview of the project’s parts/modules can also be included. Ideally, your OSH project would be designed using a free and open source software application, to maximize the ability of others to view and edit it. It is essential to share these original design files, in both original and accessible ready-to-view formats. The type of parts can also be mentionned with unambiguous reference, between, custom parts (developed as a result of this or another project), off-the-shelf parts (like screws) or (maybe proprietary) complex modules (for example, a single board computer).

Software and firmware: You should share any code or firmware required to operate your hardware. This will allow others to use it with their hardware or modify it along with their modifications to your hardware. Document the process required to build your software, including links to any dependencies (for example, third-party libraries or tools). In addition, it is helpful to provide an overview of the state of the software (for example, “stable” or “beta” or “barely-working hack”).

Instructions for operation and maintenance: Describe how hardware users should operate the hardware (for example how to calibrate and test it). Indicate any maintenance that should be done to secure a good functionality of the hardware.

Repair and disposal: Indicate where or how the hardware can be repaired, and indicate how to dispose or recycle the hardware, if it is beyond repair.

Note that producing documentation-quality pictures consistently requires adequate tools and setup.

Community documentation#

While open hardware communities are sometimes different than open software communities, the documentation useful to grow hardware communities are similar to those for a open source project, see the pd-overview-repro chapter. You may want to refer to the collaboration and cl-new-community guide of The Turing Way book for a more detailed description of certain aspects such as practices, metrics, behaviors and observables that can be related to thriving communities.

OSH communities come in all sizes and forms. They often develop around people facing similar needs, who realise they will get “something that none of [them] could have developed alone.” (Interview: White rabbit, by the Open make team, Javier Serrano and Amanda Diez Frenandez .) We should therefore consider that developing good quality hardware and making it open source already entails an important aspect of community building.

In the following section, we share some considerations about community building for OSH project.

Considerations for OSH community building#

While scoping your project, it is well advised to think about the different people who may engage with your OSH (see cl-stakeholder-mapping). Different OSH projects have included different partners at varying stages of their developement. On top of user and contributor roles that OSH have in common with open source software, local or global hardware manufacturers may become important partners of your project. You may also think early about the people who will eventually have to maintain and repair the hardware. To make it easier for them, it also helps to make your hardware designs modular (splitting your hardware in modules which may have alternative designs). Another specificity of hardware may be the importance of the creation of replication tutorials, workshops, seminars, or training materials, which can impact the adoption of hardware designs. This is particularly relevant if the OSH is meant to be produced in Do-It-Yourself environments or as a teaching opportunity.

Note

Engineering culture can still be a closed one, not very welcoming to newcomers from different backgrounds.

It is therefore particularly important to Valuing Diversity and Differences in OSH cl-new-community-differences

It is important to decide whether, when and where you want to engage with, or build a community. Most OSH communities are local in comparison to open source software project. You may not have the time or skills to build a community, and your project may not need a community to flourish. Always be honest with your collaborators and yourself about what support they can expect. The GOSH forum has been an enabler for finding collaborators for OSH and OSH-related projects.

Learning from community roadblocks

It is better to keep an open attitude towards diversification and unstable features, and this does not need to be in conflict with the main project being conservative.

There should always be space for “extensions” and “plugins” to be seeded and grow in the same community as the main project. 3rd-party plugins should be labeled as “external and unsupported by mainline development” but still encouraged.

It is good practice to build modular and extensible hardware, with documented interfaces, to be able to grow a developer community.

It is a bad idea to respond to a request for help with the following: “It is ‘open source’, if you want that to happen, you are free to work on it in your own time”. Be honest of what you can do, but do not be a jerk.

If the upstream developers do not have time to write enough documentation, or do not have time to review pull requests, this fact should be stated to avoid generating false expectations.

Be ready to delegate (or create new spaces) if you are overwhelmed by a fast-growing community. Otherwise, small projects will stall, the community will be frustrated, and then become fragmented.

Sharing open source hardware#

One of the goals of making OSH is to share the documentation so others can reuse your project (build upon, improve, derive from). Once a project is shared, it can be continuously developed and manintained.

For OSH to be effectively adopted, reused, and developed further, the hardware documentation and other relevant information needs to be shared in a way that is easily accessible at no cost. The global open hardware community utilizes a variety of platforms and online resources to share their work and enable others to collborate on different projects. The details on the some of the platforms used and their efficacy is discussed further in the following section Platforms.

Platforms#

The easiest way to share an open hardware project is by sharing it online. There is no best platform or place to do this, as it depends on the specifics of your project. However, some platforms commonly used for OSH are GitHub, GitLab, Wikifactory and hackaday.io. Please refer to cl-github-novice for an introduction to GitHub and GitLab. Some hardware project have large files, and one may need to look for platforms and workflows allowing to work with big files (see rr-vcs-data).

Making hardware discoverable#

There is (yet) no straightforward way to let others to know about your project online. Here we list some actions you may take in order to make your project more visible, reach more people, and improve the chances of reproducibility:

Use a commonly used platform; often they have a discovery page and people expect your project to be on such platforms.

Use metadata to discribe your project, apart from just your technical data it is also important to share the metadata of your project, for example a short disciption, a statement of the license, the context of your project. Adding a Open-Know-How manifest yaml file may help.

Refer to the guide for communication cm-comms-overview and make a presskit or media content for others to easily share your project on other blogs or websites.

In academia, researchers may also publish their hardware (usually at the demonstrator stage), as peer-reviewed articles and archive a version to generate a DOI.

Making hardware citable#

In contrast to data and software, there is no recommendation for hardware citation yet. However, we think it is good practice to treat hardware citation similarly to other research ouptuts cm-citable. Making open hardware citable is indeed useful for academic and research output. The use of archives that can assign persistent identifiers (DOI) can help to guarantee specific versions/releases of the hardware project available over the long term. Though within the open hardware community this is not the practice, it would be beneficial to adopt going forward. For research to be reproducible, long term archiving through a platform that is dedicated to it would be necessary.

Zenodo is a good example of the type of archive that can issue a persistent identifier like a DOI. Zenodo also has an integration with Github such that projects that are shared and developed there can be archived with ease and a DOI obtained for a specifc version/release.

Open source hardware licencing#

A crucial step to making OSH open is by adding an open license. Without an open license, others cannot legally use, copy, distribute, or modify that project. The situation of hardware licensing is a bit more complex than for research outputs like software, as there are some cases where patent law and not copyright law will apply. Also note that you may use different licenses for different part of the project.

Please refer to rr-licensing and rr-licensing-hardware.

Common OSH license are:

Similar to GNU GPL 3.0, SOLDERPAD

Similar to Apache License 2.0, CERN-OHL 2 which comes as:

CERN-OHL-S (Strongly reciprocal)

CERN-OHL-W (Weakly reciprocal)

CERN-OHL-P (Permissive).

References/glossary#

Standardisation of Practices in Open Source Hardware by []

This Chapter of the book was created reusing the following documents:

Open Hardware Academy: https://www.openhardware.academy/03_Lessons.html

Open Hardware Makers: https://curriculum.openhardware.space/

UKRN primer on open science hardware