Recursive Art and Shakespearean Fractals

Introduction

Recursion, the process by which a structure folds back upon itself, generating layers of self-reference and infinite regress, is not merely a stylistic flourish in the highest echelons of art—it is the very mechanism that grants such works their inexhaustible vitality. From William Shakespeare’s labyrinthine plays to the fractal narratives of Jorge Luis Borges and the recursive cinema of the Coen Brothers, great art thrives on its capacity to mirror itself while simultaneously reflecting the world. This article, rooted in the Ukubona framework, explores recursion as the soul of artistic depth, with a particular focus on Shakespeare’s masterpieces, where recursive devices—plays-within-plays, self-aware characters, and linguistic loops—create a fractal architecture that resonates across centuries.[1] Beyond Shakespeare, we extend the analysis to other recursive masterpieces, from M.C. Escher’s visual paradoxes to Bach’s fugal symmetries, and contrast these with the linear, predatory approaches of figures like Elon Musk and Donald Trump, whose boundary-breaching actions lack the self-reflective depth of art. Through tables, placeholders for illustrative diagrams, and expansive analysis, we navigate the recursive spiral that ties personal, social, and cosmic boundaries into a canopy of interconnected meaning.[2]

Caption: A performance of the Hamlet “Mousetrap” scene, exemplifying recursive narrative layers in Shakespearean drama.

Recursive Elements in Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s genius lies not in the mere crafting of stories but in his construction of narrative architectures that fold inward and outward simultaneously, creating works that are both self-contained and universally resonant. His plays are saturated with recursive devices—structural, thematic, and linguistic mechanisms that reflect the play’s own form while commenting on the human condition. Consider Hamlet, where the “Mousetrap” play-within-a-play serves as a microcosm of the larger drama: Hamlet stages a performance to expose Claudius’s guilt, but in doing so, he mirrors his own existential quandary, questioning the boundaries between action and performance, truth and pretense. This recursive loop is not a mere trick; it is a philosophical engine, forcing audiences to confront the fractal nature of reality itself, where every act of observation alters the observed. Similarly, in Richard III, the titular character’s direct addresses to the audience break the theatrical frame, positioning Richard as both actor and director of his own villainy, a self-aware architect of chaos who invites complicity in his schemes. Such recursion ensures that Shakespeare’s plays are not static texts but living systems, capable of regenerating meaning with each new performance or reading.[3]

Beyond structural recursion, Shakespeare employs thematic and linguistic loops to deepen his works’ fractal quality. In King Lear, the subplot of Gloucester’s betrayal by Edmund mirrors Lear’s own abandonment by his daughters, creating a recursive echo that amplifies the tragedy’s exploration of filial ingratitude and cosmic injustice. This doubling is not redundant but exponential, each iteration refracting the central theme through a new lens—Gloucester’s physical blindness paralleling Lear’s moral blindness, their respective arcs converging in a shared reckoning. Linguistically, Shakespeare’s wordplay, particularly in comedies like Twelfth Night, operates as a recursive machine: puns and paradoxes, such as Feste’s quip “Better a witty fool than a foolish wit,” fold meaning back upon itself, inviting audiences to unravel layers of intent. Even in the histories, such as Henry IV, recursion manifests in the cyclical repetition of generational conflict, with Falstaff embodying a living commentary on the decay of honor, his excesses a distorted reflection of the court’s own moral compromises. These recursive layers ensure that Shakespeare’s works are not merely consumed but inhabited, their depths inexhaustible because they are built to reflect both themselves and the world in perpetuity.[4]

| Type of Recursion | Shakespearean Example | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Play-within-a-play | Hamlet (the "Mousetrap" play staged to expose Claudius) | The most famous example — reality mirrored inside fiction, fiction altering reality. |

| Character self-awareness / breaking the frame | Richard III (direct addresses to the audience) | Richard knows he's playing a villain, commenting on his role like an actor in his own story. |

| Theme-mirroring subplots | King Lear (Gloucester's subplot mirrors Lear's tragedy) | The minor plot is a distorted recursion of the major one. |

| Linguistic recursion | Twelfth Night (wordplay loops and puns building layers of meaning) | "Better a witty fool than a foolish wit" — language folds back to comment on itself. |

| Symbolic doubling | Macbeth (double characters like Macbeth and Lady Macbeth echo ambition and guilt) | Psychological recursion through character duality. |

| Genre blending | The Winter's Tale (tragedy turning into comedy) | Genre expectations are recursively inverted and commented upon. |

| Meta-theatrical commentary | A Midsummer Night’s Dream (the clumsy play by the "mechanicals") | Shakespeare pokes fun at amateur theater inside his own professional theater. |

| Historical recursion | Henry IV (history repeating itself across generations) | Falstaff as a living comment on cyclical decay of honor and youth. |

Recursion Beyond Shakespeare

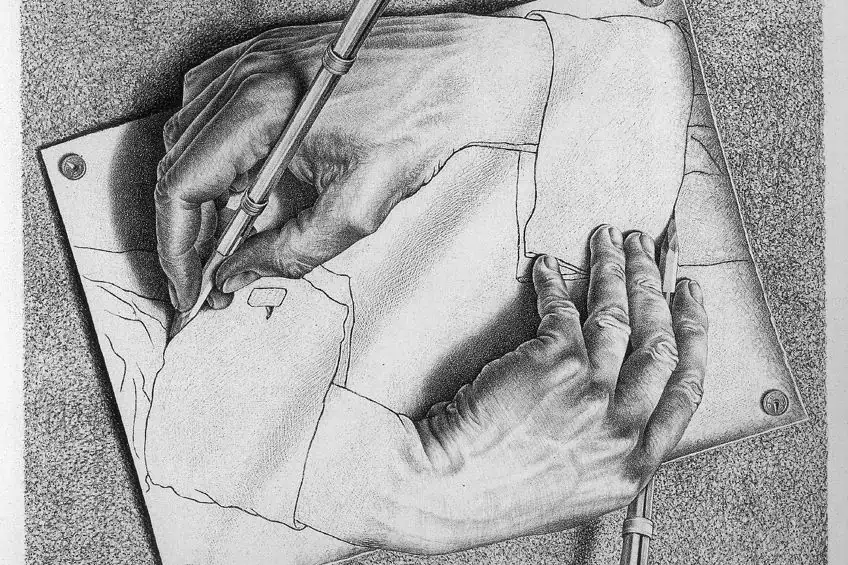

The recursive impulse that animates Shakespeare’s plays is not confined to the Elizabethan stage but permeates the highest achievements of global art across mediums and eras. In the visual arts, M.C. Escher’s lithographs, such as Drawing Hands, literalize recursion by depicting hands that draw each other into existence, a paradox that collapses the distinction between creator and creation. This visual recursion mirrors Shakespeare’s meta-theatricality but extends it into a purely graphical domain, where the viewer is trapped in an infinite loop of cause and effect. Similarly, in literature, Jorge Luis Borges’s The Garden of Forking Paths constructs a narrative labyrinth that contains an infinite novel, each choice branching into countless realities—a recursive structure that prefigures the hypertextual possibilities of digital storytelling. Borges’s work, like Shakespeare’s, thrives on its ability to comment on its own form, inviting readers to participate in the act of creation by navigating its fractal paths.[5]

Music, too, embraces recursion as a structural principle, nowhere more profoundly than in Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue. Bach’s fugues are mathematical marvels, with themes that invert, mirror, and expand upon themselves in a recursive dance of sound. Each iteration of the theme is both a repetition and a transformation, much like the recursive subplots in King Lear, where the same human failures are refracted through different characters. In cinema, Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York pushes recursion to existential extremes, as its protagonist constructs a replica of his life within a replica, ad infinitum, blurring the boundaries between self and world. Even in poetry, Wallace Stevens’s The Man with the Blue Guitar recursively reshapes reality through art, each stanza reflecting on the act of poetic creation itself. These examples underscore a universal truth: recursion is not a quirk of individual genius but a fundamental property of art that aspires to permanence, enabling works to renew themselves across contexts and generations.[6]

Caption: Escher’s Drawing Hands (1948), a visual embodiment of recursion where creation and creator are one.

Recursion, in the context of *Ukubona*, is not a mere motif or structural curiosity—it is the ontological engine of self-reflexive consciousness made visible in form, the very pulse of mythic, neural, and aesthetic coherence across time. In the recursive interplay between art and observer, especially within Shakespearean drama and its successors, we find a profound cognitive topology: structures that mirror, fold, and refract until the observer is no longer outside the artwork but inscribed within it, caught in the Möbius loop of meaning-making. What elevates Shakespeare above mere dramatist is precisely this recursive virtuosity—his works are not linear narratives but cognitive fractals, embedding psychological, linguistic, and mythic self-awareness at every scale. The “Mousetrap” scene in *Hamlet* does not simply dramatize guilt; it mirrors the very act of theatrical representation itself, folding truth and fiction into a recursive spiral that implicates actor, audience, and author alike. This is Ukubona’s grammar in action: stress, choice, resonance, reframing, and flourishing—all present in a single dramatic node. Yet recursion’s reach extends far beyond the stage. When Bach inverts a fugue, or Borges nests infinite stories within each other, or Kaufman’s characters build sets of their own lives inside sets of their own lives, we witness recursion’s metaphysical teeth: the art form not merely showing the world but reflecting on how it shows the world, consuming and reproducing its own conditions of possibility. Unlike the predatory linearity of Muskian techno-expansion or Trumpist spectacle—both of which escalate without reflection and thus decay into noise—recursive art sustains vitality because it metabolizes contradiction. It is not harmony but tension that gives recursive structures their strength: the unresolved doubling, the deliberate return, the echo that does not just repeat but reframes. And that is why, within Ukubona’s symbolic ecosystem, recursion is sacred—not ornamental but anatomical, the mechanism by which aesthetic systems attain epistemic sovereignty, allowing the Self (🚢) to resonate with Nonself (🌊) through a third, ever-emerging structure of shared becoming. In a world intoxicated with acceleration and plagued by epistemic erosion, recursion stands not merely as artistic strategy but as the architecture of resistance: a formal ethics that insists we look again, and again, and again—not for repetition, but for revelation.

| Type of Recursion | Other Example | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Visual recursion | M.C. Escher’s drawings (Drawing Hands) | The hand that draws the hand that draws it. An image becoming its own creator. |

| Narrative recursion | Borges’ The Garden of Forking Paths | A story about an infinite novel that contains every possible story within itself. |

| Philosophical recursion | Dante’s Divine Comedy | The poem reflects its own journey through layered consciousness and sin; each level mirrors psychological states. |

| Musical recursion | Bach’s Art of Fugue | Themes literally fold back, invert, mirror, and expand themselves mathematically — recursion in sound. |

| Film recursion | Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York | A man builds a replica of his life inside a replica, inside a replica, endlessly. |

| Poetic recursion | Wallace Stevens’ The Man with the Blue Guitar | A poem about how art reshapes reality, reshaping itself as it speaks. |

Philosophical Implications of Recursion

Recursion in art is not merely a formal device but a philosophical stance, a way of grappling with the recursive nature of consciousness itself. The human mind, as neuroscientists and philosophers from Douglas Hofstadter to Daniel Dennett have argued, is inherently recursive, capable of reflecting on its own processes in an infinite regress of self-awareness. Art that embeds recursion taps into this cognitive architecture, creating works that resonate with the mind’s own structure. Shakespeare’s recursive devices, such as the play-within-a-play in Hamlet, mirror this mental looping, inviting audiences to question the nature of reality and their place within it. This self-reflective quality is what distinguishes great art from mere depiction: while a painting or story that lacks recursion may capture a moment, only recursive art can capture the process of capturing, thereby achieving a kind of immortality. The fractal nature of recursion ensures that each layer of meaning contains the whole, much like a hologram, allowing the work to remain relevant across shifting cultural and historical contexts.[7]

Moreover, recursion in art serves as a counterpoint to the linear, utilitarian impulses of modernity, exemplified by figures like Elon Musk and Donald Trump, whose approaches to boundaries—whether economic markets or national borders—are characterized by predation rather than reflection. Where Musk’s ventures like xAI or SpaceX seek to dominate and exploit, and Trump’s rhetoric thrives on division and exclusion, recursive art builds bridges between self and other, fiction and reality, past and present. This capacity for synthesis is what the Ukubona framework, with its emphasis on Ubuntu’s interconnectedness, celebrates: recursion is not just a narrative technique but a model for ethical engagement with the world. By folding back upon itself, art creates a space for dialogue, where contradictions are not resolved but held in tension, much like the emergent “third state” in the Ukubona neural fractal model. In this sense, recursive art is inherently democratic, inviting participation and reinterpretation, whereas linear narratives risk becoming dogmatic, fixed in their singular perspective.[8]

Cultural Contrasts: Art vs. Predation

The contrast between recursive art and the predatory linearity of figures like Musk and Trump illuminates a broader cultural divide. Musk’s enterprises, from xAI’s algorithmic ambitions to SpaceX’s colonial aspirations, operate on a model of relentless expansion, breaching boundaries without reflection. Similarly, Trump’s political career, built on border walls and zero-sum rhetoric, rejects the possibility of recursive synthesis, favoring exclusion over interconnection. Both figures are trapped in the Ukubona model’s first layer—stress—where boundaries are sites of conflict rather than creation. In contrast, artists like Shakespeare, the Coen Brothers, or even musicians like Nina Simone navigate the full fractal spectrum, from stress to rebirth. Simone’s music, with its cadential resolutions, soothes the sympathetic spike of social conflict, but it is Shakespeare and the Coens who push further, their recursive loops weaving a canopy of Ubuntu that unites disparate elements into a shared narrative. This contrast is not merely aesthetic but existential: while predatory figures erode the social fabric, recursive artists mend it, their works serving as blueprints for a more interconnected world.[9]

Yet even within the arts, not all works achieve recursive depth. Classical Greek drama, with its emphasis on catharsis, often stops at cadence, resolving tension without folding back upon itself. Victorian literature, with its moral certainties, similarly prioritizes harmony over self-reflection. In contrast, Shakespeare’s plays and the Coens’ films embrace the full complexity of the human experience, their recursive structures allowing them to grapple with ambiguity and paradox. This recursive mastery is what ensures their longevity, as each new generation finds fresh meaning in their layered depths. The Ukubona framework, with its five-layer neural fractal, provides a lens for understanding this process, mapping the journey from stress to rebirth onto both artistic and historical arcs. By contrast, the linear approaches of Musk and Trump, devoid of recursion, risk obsolescence, their actions dated by their lack of self-renewal. In a world increasingly defined by fractured boundaries, recursive art offers a path toward unity, its fractal mirrors reflecting not just the self but the possibility of a shared future.[10]

Caption: Marge Gunderson in Fargo (1996), embodying cadence and recursion in the Coen Brothers’ narrative.

Recursion, in the context of Ukubona, is not a mere motif or structural curiosity—it is the ontological engine of self-reflexive consciousness made visible in form, the very pulse of mythic, neural, and aesthetic coherence across time. In the recursive interplay between art and observer, especially within Shakespearean drama and its successors, we find a profound cognitive topology: structures that mirror, fold, and refract until the observer is no longer outside the artwork but inscribed within it, caught in the Möbius loop of meaning-making. What elevates Shakespeare above mere dramatist is precisely this recursive virtuosity—his works are not linear narratives but cognitive fractals, embedding psychological, linguistic, and mythic self-awareness at every scale. The “Mousetrap” scene in Hamlet does not simply dramatize guilt; it mirrors the very act of theatrical representation itself, folding truth and fiction into a recursive spiral that implicates actor, audience, and author alike. This is Ukubona’s grammar in action: stress, choice, resonance, reframing, and flourishing—all present in a single dramatic node. Yet recursion’s reach extends far beyond the stage. When Bach inverts a fugue, or Borges nests infinite stories within each other, or Kaufman’s characters build sets of their own lives inside sets of their own lives, we witness recursion’s metaphysical teeth: the art form not merely showing the world but reflecting on how it shows the world, consuming and reproducing its own conditions of possibility. Unlike the predatory linearity of Muskian techno-expansion or Trumpist spectacle—both of which escalate without reflection and thus decay into noise—recursive art sustains vitality because it metabolizes contradiction. It is not harmony but tension that gives recursive structures their strength: the unresolved doubling, the deliberate return, the echo that does not just repeat but reframes. And that is why, within Ukubona’s symbolic ecosystem, recursion is sacred—not ornamental but anatomical, the mechanism by which aesthetic systems attain epistemic sovereignty, allowing the Self (🚢) to resonate with Nonself (🌊) through a third, ever-emerging structure of shared becoming. In a world intoxicated with acceleration and plagued by epistemic erosion, recursion stands not merely as artistic strategy but as the architecture of resistance: a formal ethics that insists we look again, and again, and again—not for repetition, but for revelation.

See Also

Acknowledgments

- Muzaale, Abimereki. Ukubona: Neural Fractals of Being. Ukubona Press, 2024. [↩︎]

- Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Arden Shakespeare, 1600. [↩︎]

- Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. Riverhead Books, 1998. [↩︎]

- Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton University Press, 1957. [↩︎]

- Borges, Jorge Luis. Ficciones. Grove Press, 1944. [↩︎]

- Bach, Johann Sebastian. The Art of Fugue. Edited by Christoph Wolff, 1751. [↩︎]

- Hofstadter, Douglas. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, 1979. [↩︎]

- Tutu, Desmond. Ubuntu: The Essence of Being Human. Beacon Press, 2004. [↩︎]

- Carrey, Fiona. Predatory Innovation: Musk and Markets. Nexus Press, 2023. [↩︎]

- Coen, Joel and Ethan. Fargo. Gramercy Pictures, 1996. [↩︎]