Part 1#

Warning

“What is the meaning of a philosopher paying homage to ascetic ideals?” We get now, at any rate, a first hint; he wishes to escape from a torture. - The Genealogy of Morals

Marxist philosophy, much like monotheism, envisions a final state of static equilibrium, where contradictions cease and an ideal, conflict-free society emerges. Both Marxism and monotheism posit an ultimate end: in monotheism, it’s divine harmony, salvation, or paradise, while in Marxism, it’s the classless, stateless society where material conditions no longer produce conflict. This teleological framework is a core similarity.

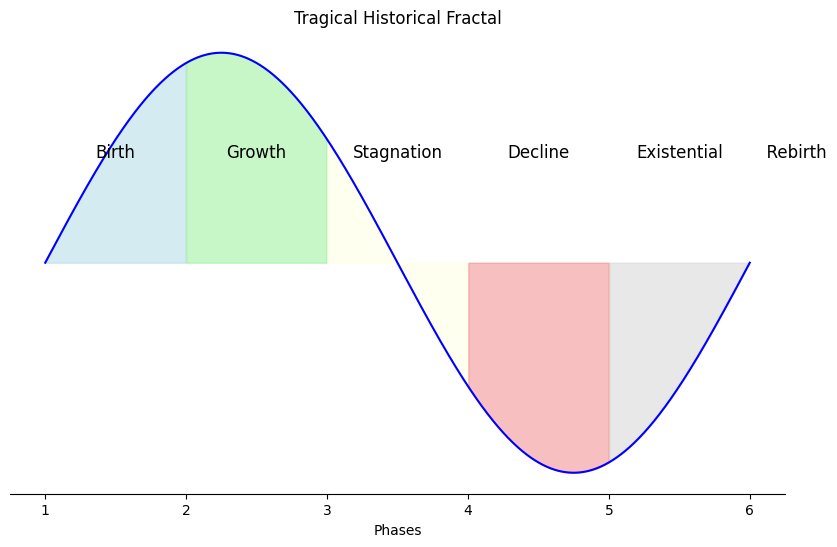

Monotheism’s narratives often depict a history of dynamic conflict—whether it’s theomachy (wars among gods or between gods and mortals) or the cycles of rise and fall in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream in the Book of Daniel. The dream itself—a series of successive kingdoms, each represented by different materials in the statue—suggests a recurring theme of power dynamics, much like Marx’s stages of economic history. The idea that the final kingdom (in monotheistic terms, often the Kingdom of God) will be eternal and unshakable echoes Marx’s vision of communism as the end of history and human struggle.

Both Marxism and monotheism imply that history has been a chaotic, conflict-laden process but is ultimately directed toward a final state of unity and peace. This notion of an “end” is static equilibrium, contrasted with the dynamic equilibrium of past struggles and changes, which both systems believe are driven by inherent contradictions—be they between classes or between moral good and evil.

The difference, of course, lies in the mechanisms: for Marx, it’s materialist, rooted in economics and social structure. For monotheism, it’s spiritual and moral, driven by divine intervention or cosmic justice. But both share this eschatological dimension, envisioning a final, harmonious state where the struggles that have defined history are resolved once and for all. It’s the ultimate stillness after the storm of history.

The irony is that, in both cases, what precedes this final state is often more interesting and dynamic—the constant tension and motion that gives rise to creativity, conflict, and human development. The static end envisioned by both feels almost too simple, as if reducing the vast complexities of human life and history to a singular, peaceful resolution risks missing the richness of the process itself.

Rebuttal#

Nietzsche’s critique of such static visions—whether in Marxism or monotheism—is biting. By calling it “the sabbath of all sabbaths,” Nietzsche is mocking the idea of an eternal rest, a final, absolute peace after all the struggles of history. He saw this as a form of nihilism—a denial of life’s inherent dynamism, conflict, and growth. To Nietzsche, life is not about reaching a final, static state of perfection, but about embracing the eternal recurrence of struggle, creativity, and becoming.

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche talks about the Übermensch (Overman) as one who rejects the comfort of static equilibrium, embracing life as a series of perpetual challenges and transformations. For Nietzsche, this ultimate sabbath—the notion of an eternal rest from conflict—was a dangerous illusion. It represents the death of the human spirit, the flattening of existence into a sterile peace. In contrast, Nietzsche championed the chaos and uncertainty that drive human greatness and creativity.

Where Marx might see the end of class struggle as the triumph of history, Nietzsche would see it as a form of stagnation, a denial of the “will to power.” For Nietzsche, the very essence of life is in its flux, in its capacity to overcome itself, and he rejected any philosophy or system that sought to bring that process to a halt. The sabbath of all sabbaths is, in Nietzsche’s view, a retreat into passivity, a longing for death disguised as utopia.