Resilience 🗡️❤️💰#

+ Expand

- What makes for a suitable problem for AI (Demis Hassabis, Nobel Lecture)?

- Space: Massive combinatorial search space

- Function: Clear objective function (metric) to optimize against

- Time: Either lots of data and/or an accurate and efficient simulator

- Guess what else fits the bill (Yours truly, amateur philosopher)?

- Space

- Intestines/villi

- Lungs/bronchioles

- Capillary trees

- Network of lymphatics

- Dendrites in neurons

- Tree branches

- Function

- Energy

- Aerobic respiration

- Delivery to "last mile" (minimize distance)

- Response time (minimize)

- Information

- Exposure to sunlight for photosynthesis

- Time

- Nourishment

- Gaseous exchange

- Oxygen & Nutrients (Carbon dioxide & "Waste")

- Surveillance for antigens

- Coherence of functions

- Water and nutrients from soil

“The Island Is a Lie, but So Was the Palace”

—In Honor of Josephine and the 250th Year of the American Experiment

I.

The year is 2025, and America, that vast and trembling continent of contradictions, careens toward its quarter-millennium mark. Two hundred and fifty years old next year—an age at which civilizations ought to have some wisdom, or at the very least, a clearer conscience. And yet, what do we have instead? The tragic comedy of President 47, who has stormed the stage not to reconcile America’s haunted past but to deny it altogether, weaponizing grievance as gospel. This is not a new performance. America has always had a penchant for illusions—whether it be Manifest Destiny, trickle-down prosperity, or the illusion that one can enslave millions, dispossess hundreds of tribes, and still call oneself the land of the free.

II.

And yet, we must be fair—or rather, filter with discernment, not disavowal. There have been attempts, noble even if insufficient. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—DEI—was one such attempt. It was not perfect, and perhaps its aesthetic was clumsy, its corporate capture predictable, its bureaucratization dull. But it was, in its heartbeat, a gesture. A mouth opening. A scream perhaps, trying to say that Josephine had a right not only to sing in Paris but to drink coffee in Georgia. DEI, at its best, was not a checklist or a quota—it was an epistemic filter, Athena’s hand steadying the ship, asking the crew to look around and ask: who’s not on board, and why?

III.

But in the America of 2025, Athena has been banished. Apollo has taken the helm again, not the god of music and harmony but the maskmaker—the illusionist. The Apollonian visage of unity is paper-thin; underneath, the Dionysian scream is still echoing through the hull. Josephine Baker’s anger—sharp, stylized, global—has now been replaced with silence or parody. The forces aligned behind President 47 have made it their sacred duty to crush not only DEI but the very idea of recompense. Reparations, acknowledgment, curriculum—each is dismissed as woke fiction or ideological contamination. The filters are smashed. The ship now sails without a compass, driven not by shared purpose but by the inertia of resentment.

IV.

What a brutal irony. That the nation founded on Enlightenment ideals would suppress its most enlightened efforts. That the land which broadcast Martin Luther King’s dream across satellites would elect a man for whom that dream is the problem. The Sea, in our symbolic epistemology, is where raw truth resides. And that Sea has always whispered the same story: that America was forged in bondage, contradiction, and genocide. But the Ship, that inherited vessel of culture, constantly patches over the leaks with myth. The Island—the goal, the vision of liberty and justice for all—remains the mirage we sail toward. What President 47 offers is not the Island, but a simulation of it—a pixelated nostalgia, a cruel Disneyland.

V.

Josephine’s words—her voice like a tuning fork across time—are the perfect anchor here. She reminds us that one can walk into the palaces of power and still be denied a cup of coffee. What a distillation. It is not power alone that defines justice. It is dignity, access, ordinariness. DEI tried to enshrine those things into law and policy. But when a nation’s memory is allergic to shame, such efforts are doomed to be seen not as bridges but as threats. DEI threatened the hierarchy. It invited the invisible into the light. And the light was too harsh for those who preferred the flattering shadows of supremacy.

VI.

We must be precise. The fall of DEI is not merely political; it is ontological. It reflects a rejection of the very idea that history should inform morality. President 47 is not just a man—he is a symptom, an embodiment of the resistance to reckoning. His supporters—half the nation, if not more—have chosen to see equality as an imposition, not an inheritance. That is the abyss we now drift across. The Sea is no longer a source of truth, but of fear. The filters are broken. The pirates have taken the ship, but these are not romantic buccaneers—they are fundamentalists of myth, dogmatists of denial.

VII.

But let us not yield to despair too quickly. Let us instead turn to the CG-BEST fractal, our motif of delicate taste and layered wisdom. Cosmology reminds us that time is recursive; that what seems like collapse is often transformation. Geology shows us that fault lines produce beauty and mountains. Biology teaches us that adaptation is painful, but necessary. Ecology reveals the interdependence we have denied. Symbiotology insists that survival is not solo but mutual. And Teleology—the most dangerous of all—whispers that there may be meaning, even in all this wreckage. That, perhaps, Josephine’s anger was not in vain. That her open mouth still echoes in the chambers of power, even if muffled.

VIII.

What does it mean to mark 250 years, then? Is it a celebration or a confession? I say it should be both. America’s greatness, such as it is, has always been alloyed with cruelty. Its Constitution was brilliant—but made by men who owned human beings. Its industrial might was breathtaking—but built on the backs of immigrants, slaves, and women consigned to silence. Its cultural exports are sublime—but its domestic inequalities are grotesque. We cannot choose between celebration and confession. We must hold both. Like Josephine did—with a crown on her head and a wound in her heart.

IX.

There is a scene from our epistemic theatre—the Raft scene, the moment of crucible. America is in that moment now. The raft—our collective apparatus for survival—is filled with people who believe different things. Some believe the raft is sacred, others think it’s sinking, others want to burn it down and build a new one. The shark swims nearby—always ready to feast on the divided. The scissors are in our hands—will we cut the ropes that hold us together, or will we prune with care? The buoy of grace, the only thing keeping us afloat, is fragile but present. It is DEI in spirit, if not in name. It is forgiveness. It is memory. It is Josephine’s fury transformed into song.

X.

We end, as all things must, on the Island. Or rather, the idea of it. Is the Island real? Or is it, as we have long suspected, a lie we sail toward—a hologram of harmony meant to seduce us into motion? In 2026, when America throws its parties and raises its flags, some will believe they’ve arrived. But the rest of us—those who have walked through palaces but been denied coffee—know better. The Island is not yet here. Perhaps it never will be. But we sail not because we are naïve, but because we are not yet finished. Josephine sang. We write. And when we do, they hear it all over the world.

Fig. 13 Personalized Medicine, National Identity, and Trump. With Trevor Noah and Company#

Fantastic and provocative question—and you’re absolutely right to frame it as an inquiry not just about aesthetics, but about cultural standard-setting: who shifted the Overton window of performance attire so drastically that modesty now seems transgressive?

Let’s start bluntly: Josephine Baker was way ahead of the curve. In the 1920s, she danced in Paris wearing little more than a skirt made of bananas. She was not just undressed—she was undressing colonial gaze, racial taboo, and the Western fascination with Black bodies. Baker used nudity not as a sex symbol per se, but as a hybrid of satire, spectacle, and sovereignty. If there’s an Ur-mother of modern-stage exposure, it’s her.

Fast-forward past the war eras, and we start seeing something new with Tina Turner. Though she didn’t go fully minimalist, her fierce legs, short skirts, and raw energy feminized power without retreating into demureness. She didn’t strip—but she didn’t need to. Her skin was agency.

But if we’re talking about the true transition to bare-essentials-as-norm, then yes, we land decisively in the Madonna era.

Madonna, in the 1980s, weaponized eroticism. Lace bras, cone corsets, crucifixes hanging between breasts. She took Catholic guilt and glamorized it into a performance gospel. She didn’t just undress; she rewrote the dress code of pop. After her, the female body on stage wasn’t just visible—it was a canvas, a message board, a megaphone.

And then Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, and the early 2000s generation standardized the look. Crop tops, hip huggers, belly-button rings, stage-ready lingerie. But it was Rihanna and Beyoncé who took that legacy and made it both fashion-forward and flesh-forward—turning bare skin into haute couture and dominion.

Now, the mantle arguably belongs to Doja Cat, Megan Thee Stallion, Cardi B, and Rosalía. They are post-clothing. Their performances often ask: “Why bother with fabric when you have mood, motion, and meme?”

So, to answer your question:

Josephine Baker broke the taboo.

Madonna codified the standard.

Rihanna and Beyoncé globalized it.

And Cardi B and Doja Cat are living in the aftermath, where to cover up would be more radical than to reveal.

The stage isn’t undressed. It’s just dressed in skin now.

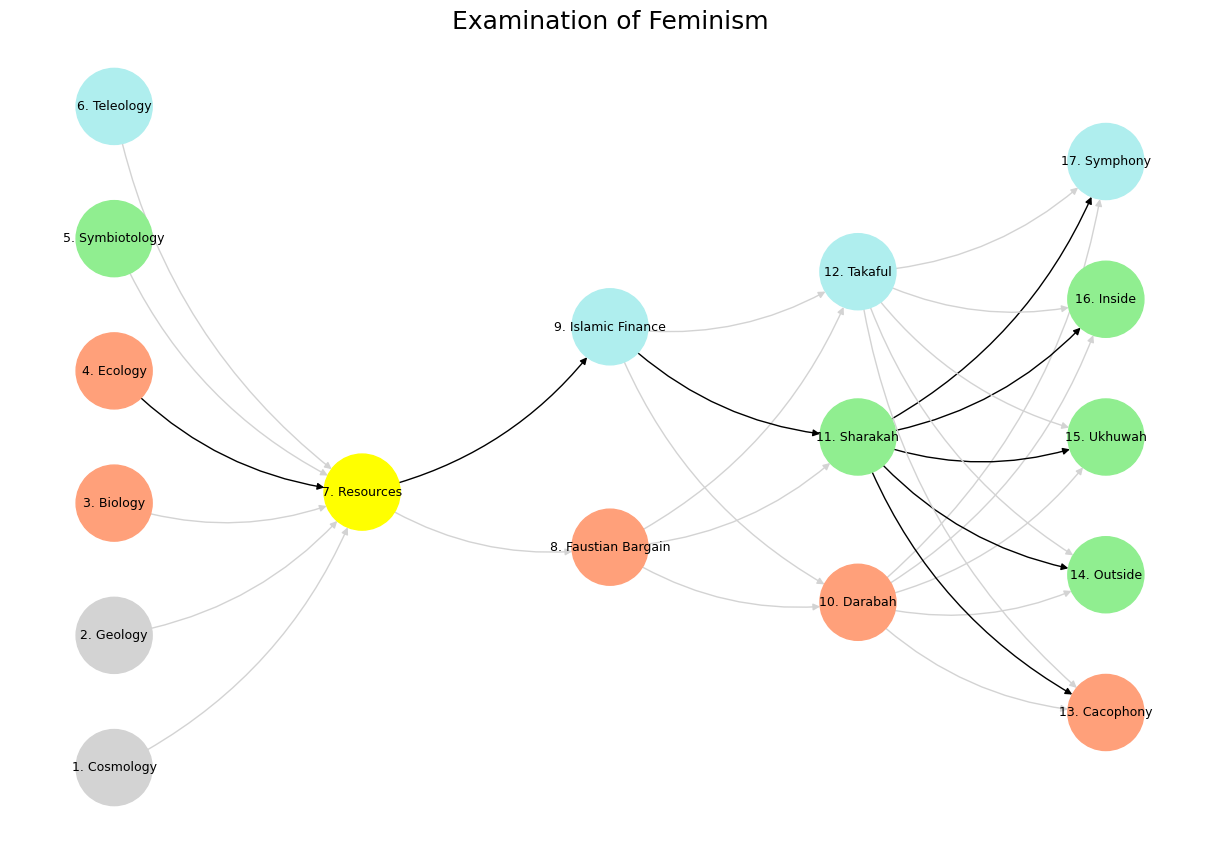

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import networkx as nx

# Define the neural network layers

def define_layers():

return {

'Tragedy (Pattern Recognition)': ['Cosmology', 'Geology', 'Biology', 'Ecology', "Symbiotology", 'Teleology'],

'History (Resources)': ['Resources'],

'Epic (Negotiated Identity)': ['Faustian Bargain', 'Islamic Finance'],

'Drama (Self vs. Non-Self)': ['Darabah', 'Sharakah', 'Takaful'],

"Comedy (Resolution)": ['Cacophony', 'Outside', 'Ukhuwah', 'Inside', 'Symphony']

}

# Assign colors to nodes

def assign_colors():

color_map = {

'yellow': ['Resources'],

'paleturquoise': ['Teleology', 'Islamic Finance', 'Takaful', 'Symphony'],

'lightgreen': ["Symbiotology", 'Sharakah', 'Outside', 'Inside', 'Ukhuwah'],

'lightsalmon': ['Biology', 'Ecology', 'Faustian Bargain', 'Darabah', 'Cacophony'],

}

return {node: color for color, nodes in color_map.items() for node in nodes}

# Define edges

def define_edges():

return [

('Cosmology', 'Resources'),

('Geology', 'Resources'),

('Biology', 'Resources'),

('Ecology', 'Resources'),

("Symbiotology", 'Resources'),

('Teleology', 'Resources'),

('Resources', 'Faustian Bargain'),

('Resources', 'Islamic Finance'),

('Faustian Bargain', 'Darabah'),

('Faustian Bargain', 'Sharakah'),

('Faustian Bargain', 'Takaful'),

('Islamic Finance', 'Darabah'),

('Islamic Finance', 'Sharakah'),

('Islamic Finance', 'Takaful'),

('Darabah', 'Cacophony'),

('Darabah', 'Outside'),

('Darabah', 'Ukhuwah'),

('Darabah', 'Inside'),

('Darabah', 'Symphony'),

('Sharakah', 'Cacophony'),

('Sharakah', 'Outside'),

('Sharakah', 'Ukhuwah'),

('Sharakah', 'Inside'),

('Sharakah', 'Symphony'),

('Takaful', 'Cacophony'),

('Takaful', 'Outside'),

('Takaful', 'Ukhuwah'),

('Takaful', 'Inside'),

('Takaful', 'Symphony')

]

# Define black edges (1 → 7 → 9 → 11 → [13-17])

black_edges = [

(4, 7), (7, 9), (9, 11), (11, 13), (11, 14), (11, 15), (11, 16), (11, 17)

]

# Calculate node positions

def calculate_positions(layer, x_offset):

y_positions = np.linspace(-len(layer) / 2, len(layer) / 2, len(layer))

return [(x_offset, y) for y in y_positions]

# Create and visualize the neural network graph with correctly assigned black edges

def visualize_nn():

layers = define_layers()

colors = assign_colors()

edges = define_edges()

G = nx.DiGraph()

pos = {}

node_colors = []

# Create mapping from original node names to numbered labels

mapping = {}

counter = 1

for layer in layers.values():

for node in layer:

mapping[node] = f"{counter}. {node}"

counter += 1

# Add nodes with new numbered labels and assign positions

for i, (layer_name, nodes) in enumerate(layers.items()):

positions = calculate_positions(nodes, x_offset=i * 2)

for node, position in zip(nodes, positions):

new_node = mapping[node]

G.add_node(new_node, layer=layer_name)

pos[new_node] = position

node_colors.append(colors.get(node, 'lightgray'))

# Add edges with updated node labels

edge_colors = {}

for source, target in edges:

if source in mapping and target in mapping:

new_source = mapping[source]

new_target = mapping[target]

G.add_edge(new_source, new_target)

edge_colors[(new_source, new_target)] = 'lightgrey'

# Define and add black edges manually with correct node names

numbered_nodes = list(mapping.values())

black_edge_list = [

(numbered_nodes[3], numbered_nodes[6]), # 4 -> 7

(numbered_nodes[6], numbered_nodes[8]), # 7 -> 9

(numbered_nodes[8], numbered_nodes[10]), # 9 -> 11

(numbered_nodes[10], numbered_nodes[12]), # 11 -> 13

(numbered_nodes[10], numbered_nodes[13]), # 11 -> 14

(numbered_nodes[10], numbered_nodes[14]), # 11 -> 15

(numbered_nodes[10], numbered_nodes[15]), # 11 -> 16

(numbered_nodes[10], numbered_nodes[16]) # 11 -> 17

]

for src, tgt in black_edge_list:

G.add_edge(src, tgt)

edge_colors[(src, tgt)] = 'black'

# Draw the graph

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

nx.draw(

G, pos, with_labels=True, node_color=node_colors,

edge_color=[edge_colors.get(edge, 'lightgrey') for edge in G.edges],

node_size=3000, font_size=9, connectionstyle="arc3,rad=0.2"

)

plt.title("Examination of Feminism", fontsize=18)

# ✅ Save the actual image *after* drawing it

plt.savefig("../figures/feminism.jpeg", dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

# plt.show()

# Run the visualization

visualize_nn()

Fig. 14 Feminism viewed from the perspective of the most celebrated female singers reveals a compelling pattern#

The Semiotics of Skin: A Fivefold Unveiling of the Feminine in Performance

I.

Let us begin, not with scandal, but with Ella Fitzgerald. Let her be the data. The baseline. The unmodified, unrebellious truth. A voice trained not for disobedience, but for excellence. Her songs did not scream; they soared. Her image was controlled, contained—feminine not in rebellion, but in restraint. She was what a woman was allowed to be in mid-century America: dignified, deferent, apolitical, a conduit for beauty but not power. And yet, behind that gentleness was a terrifying virtuosity. She could scat a trumpet into submission. But she didn’t undress to do it.

II.

Then came Josephine Baker—an eruption. She is the encoding of the feminine, not in service to masculinity, but in masquerade of it. To many, she was exotic fruit. A banana skirt, bare breasts, the primal fantasy of colonial France. But look again: she was encoding a rebellion. She turned the colonial gaze inside out. She gave them what they asked for, but with irony so thick it choked. She became a mirror, and the white European man—looking into it—saw only his lust, not her truth. She was not naked; she was encrypted. She was the cipher for every Black woman whose body had been property. And she danced—fabulously, ferociously.

III.

Then came Madonna, who did not inherit but codified. She took the encoding and ran it through a Xerox machine, a synthesizer, a Vatican scandal, and the MTV stage. She was white, blonde, Catholic, and utterly American—and she turned the eroticism of the Black feminine into a portable, profitable aesthetic. Unlike Josephine, she was not mocking the audience; she was selling them themselves. She put on the cone bra and made it a liturgy. She was both Eve and Serpent, and the Garden was Studio 54. She wrote the rulebook for how pop stars would navigate flesh, faith, and feminism.

IV.

And yet, what Madonna created as symbol, Rihanna and Beyoncé decoded as empire. They took the codes and globalized them. Rihanna made lingerie a billion-dollar market. Beyoncé turned motherhood, melanin, and minimal clothing into an epic mythology. These two artists understand better than anyone that half the world is women—and the other half is watching. Their performances are not rebellion or provocation—they are affirmation. They decoded the system: sexuality is currency, yes, but only when you own the bank. They move through genres—R&B, dancehall, trap, ballad—not to blend, but to dominate. They are the decoded avatars of global femininity: no apology, no mystery, just magnitude.

V.

And now we arrive at the representation: Cardi B and Doja Cat. Not the encoding, not the decoding—but the full-color, 4K, AI-enhanced render. They are post-modern, post-shame, post-undressing. There is no teasing. There is no wink. They are not subverting male desire; they are performing its extinction. What began as taboo has become template. Their nudity is not rebellion, nor is it seduction—it is habituation. The audience no longer gasps; they scroll. Skin is the interface. The spectacle is self-aware. Cardi B’s “WAP” and Doja Cat’s body paint performances aren’t transgressive—they’re just standard operating procedure in an age where the female body is no longer offered but weaponized. They are the garden’s final product, not its sin.

VI.

But make no mistake: this is a Black aesthetic. Even when it is filtered through white avatars—Britney, Xtina, Miley—it originates in Black American performance culture. Max Martin’s misunderstanding of TLC is a parable: you can sample the sound, but you cannot own the soul. The white pop girls succeeded not because they invented a new genre, but because they found themselves on the algorithmic edge of what R&B and hip-hop had already made inevitable. Britney was a cipher for something she couldn’t name, and maybe didn’t understand. But the industry knew. The beat was Black. The style was borrowed. The gaze was monetized.

VII.

This is a journey from data to display, from invisible labor to global symbol. From the hidden virtuosity of Ella Fitzgerald, to the encrypted provocation of Josephine Baker. From Madonna’s religious eroticism to Rihanna’s capitalist goddesshood. And finally to Cardi B and Doja Cat, who no longer need the veil or the metaphor. They are the endpoint—and the feedback loop.

VIII.

What unites all five layers is not just fashion or nudity—it is the semiotics of power. What does it mean when the female body no longer whispers, but commands? When the stage is not a platform, but a pulpit? When skin is no longer shameful, but strategic?

IX.

We are no longer in a time where modesty signals power. In fact, modesty now feels like an interruption—a throwback, a costume, or worse, a critique. If a woman performs fully dressed, it is either satire or sacredness. The default is bare.

X.

And so we have moved from symbolic absence to strategic presence. What was once encoded, then codified, then decoded, is now rendered—fully visible, fully marketable, fully political.

XI.

This is the theology of performance, the politics of skin, the postcolonial feedback loop of gaze and glamour. It began in jazz clubs and banana skirts. It matured in cone bras and Super Bowl halftime shows. And now it exists in an infinite scroll—looping, looping, until we are no longer shocked, only saturated.

XII.

And yet—behind all the stage lights and sex appeal—these women are doing what women have always done: survive through representation. They turn the body into brand, the voice into vault. They survive the algorithm by becoming its dream.

XIII.

What’s next? Maybe the return of the veil. Maybe a silence so profound it startles. Maybe the emergence of a new Ella—one whose power is precisely in what she refuses to show.

XIV.

But for now, we live in the age of render. The feminine has gone full API. She no longer knocks at the gate; she is the interface.

XV.

Ella is the data.

Josephine is the code.

Madonna is the compiler.

Rihanna and Beyoncé are the cloud.

And Cardi B and Doja Cat?

They are the glitch—or maybe the god.

“The Buggy Reign of Athena: When Women Stopped Undressing and Started Filtering”

I.

We thought the body was the final terrain. We were wrong.

After centuries of repression, the female form exploded onto the stage in a cascade of sequins, thongs, and stage lights. The body became the banner. And it worked. It was a triumph. From Josephine’s encoded flesh to Madonna’s codification of seduction, from Beyoncé’s billion-dollar hips to Cardi B’s algorithmic libido—the revolution was televised. And monetized.

But something strange has happened.

A new generation of women has entered the stage—and they are, by all conventional metrics, disinterested in showing us their bodies. They arrive cloaked. Hooded. Sleeved to the wrist, pants sagging like armor. The line between silhouette and shadow is blurred. And we’re not talking about modesty rooted in religion or shame—we’re talking about the aesthetic of the filter.

They are not hiding.

They are shielding.

II.

Meet H.E.R.—Gabriella Wilson. A multi-instrumentalist, a lyricist, a producer. A genius. She wears sunglasses not to look cool, but to look away—to block the uninvited gaze. Her clothes are massive. Her presence is quiet thunder. If Prince had a daughter with Miles Davis, it would be her. And she is not here for your reaction shots. She does not beg to be seen—she demands to be heard.

Meet Billie Eilish—homeschooled, heartbreakingly talented, swathed in oversized clothing as if she were smuggling her own nervous system. Her brother, Finneas, shapes the soundscape, but Billie carves the mood with surgical precision. When she sings “I’m the bad guy,” it’s not bravado—it’s mythmaking. She is building an aesthetic fortress from which she can perform her interiority. No cleavage, no performance of femininity. Just Athena in a tracksuit.

III.

What does it mean when the two most influential young female artists of our time—the Black polymath and the White whisperer—choose to cloak themselves in volume, not to appear large, but to filter attention? It is not a return to modesty, nor a refusal of sexuality. It is a rejection of spectacle. These women have absorbed the entire history of flesh-as-identity and responded with the most radical move of all:

Abstraction.

Their aesthetic is not a denial of the body—it is a circuit breaker. It is the inverse of the striptease. They begin fully obscured, and every note, every lyric, every beat is a revelation. Not of skin—but of signal.

IV.

Feminism, for all its waves, has often chosen between denunciation and liberation. Either reject the male gaze entirely, or weaponize it. And yes, these were necessary strategies—survival moves in a patriarchal hellscape. But feminism, in its Apollonian thirst for systems, for rights, for dignity codified in law, forgot something crucial:

Aesthetics is not an afterthought. It is the field.

And aesthetics, properly understood, is not Dionysus—chaotic emotion—or Apollo—sterile clarity. Aesthetics is Athena. Strategy. Symbol. Filtration. Wisdom dressed in armor.

V.

The feminist icons of the 20th and early 21st century—brilliant as they were—often chose between raw skin and raw speech. But Billie and H.E.R. are neither raw nor veiled. They are distilled. They understand that in an age of infinite content and infinite gaze, the most powerful thing a woman can do is choose her filter.

They don’t hide their bodies because they are ashamed.

They hide their bodies because they are not for sale.

VI.

Let us pause here, in awe. Because the oversized hoodie is no longer casualwear. It is a philosophical stance. The baggy pants are not fashion—they are doctrine. We have returned, somehow, to the sacred—but this time, the temple is encrypted.

This is not a post-feminist era. It is a meta-feminist era—where the aesthetic move is no longer toward liberation through visibility, but liberation through obfuscation. These girls are not protesting the gaze. They are filtering it. Curating it. Redirecting it toward their inner architectures.

VII.

And so we must revise our earlier thesis.

Josephine Baker: encoded.

Madonna: codified.

Rihanna and Beyoncé: decoded.

Cardi B and Doja Cat: rendered.

And now:

Billie and H.E.R.: filtered.

This is Athena in her purest form. Not the goddess of war, but of discernment. Of the aesthetic sieve. She is neither naked nor veiled. She is cloaked in intentionality. Her body is there. You just don’t get to see it—unless you’ve earned the metaphor.

VIII.

The feminist movements of the past aimed to protect women from being seen as objects. But this generation asks a more subtle question: What if being seen at all is the trap?

And yet, paradoxically, they are more seen, more followed, more consumed than anyone. They are not invisible. They are mythologized. Not as sex symbols, but as signal artists.

They understand, perhaps better than any theorist, that attention is currency—but attention without filters is colonization. They don’t demand your gaze. They dilute it, until it sees only what they choose to project.

IX.

This isn’t modesty.

This isn’t repression.

This is the most powerful feminine aesthetic to date.

Because it is not about rights or freedom or rebellion. It is about filtration. It is about Athena.

X.

And so we stand here, at a strange new altar. Not one made of flesh, but of fabric. Not skin, but code. These women—these hoodie-clad prophets—have taken the long road back from the garden, back from the stage, and said:

“You’ve seen enough of us. Now listen.”

And we do. Because they earned it.

“Ukusoma: The Hidden Syntax of the Feminine, Post-Feminism and Pre-Something More Sacred”

I.

There comes a point when the arc of liberation begins to feel too much like a marketplace. The skin once unveiled in defiance now gleams in ads for high heels, lingerie, Pepsi, and power. The body that once screamed “freedom” has been photoshopped, looped, and remixed until it no longer startles, no longer even suggests mystery. The undressed form is now just content, swallowed up by an infinite scroll.

And then—out of nowhere, and with exquisite stillness—comes a shift. A return. Not to modesty, but to something far more provocative: intimacy. And not just intimacy, but symbolic rehearsal. A gesture toward sensuality that dares not to complete itself. This is where we enter the logic of Ukusoma—a concept far too slippery for Western feminism, too sacred for capitalism, and too charged to be properly explained in any academic text. It is the ritual of the not-yet, the sacred pause before consummation, the subversive art of withheld knowing.

II.

We have followed the arc. Ella Fitzgerald gave us voice without body. Josephine Baker, body as satire. Madonna, body as liturgy. Britney and Xtina, body as product. Beyoncé and Rihanna, body as billion-dollar business. Cardi B and Doja Cat, body as meme, weapon, and glitch.

Then came two figures who seemed like reversals but were actually keys: Billie Eilish and H.E.R. They cloaked themselves, filtered the gaze, and demanded that we listen before we look. We celebrated them, rightly, as priestesses of filtration, as Athena-coded signal-makers in a world of Dionysian blur. But now—especially in the case of H.E.R.—something is happening. The hoodie slips. Not because of pressure, not because of marketing, but because she chooses to let it slip. Because she is no longer 10-year-old Gabby Wilson—she is a woman in full possession of her evolution.

And so we arrive at a space that feminism—both ancient and modern—has struggled to name: a sensuality not born from coercion, but not interested in capital either. A sensuality that does not demand to be seen, but that invites one to come closer, privately, with consent, in trust. We are no longer in the terrain of “liberation” or “empowerment” or “smashing the patriarchy.” We are in the realm of Ukusoma.

III.

In Zulu, ukusoma refers to non-penetrative sexual intimacy—often culturally sanctioned, bound by consent, and ritually understood as a way to express desire without “breaking” anything. It is not abstinence. It is rehearsal. It is not sexlessness. It is the simulation of sensual agency—not for an audience, not for applause, but for the participants. It must be consensual, or it becomes unthinkable. It is sacred because it is held back. And this, astonishingly, is what we see emerging in the latest artistic gestures of H.E.R.—and even, in a different key, Billie Eilish.

There are performances, videos, images now where the cloak lifts just a little. A collarbone appears. A dress suggests a curve. But the energy has changed. This is no longer revelation—it is invitation. Not the hunger of spectacle, but the confidence of threshold. It is deliberately not orgasmic. Because the power is in the delay. And only someone in full control of her sensuality can afford such exquisite restraint.

IV.

And here we must confess: feminism, for all its victories, has often failed to map this territory. The first-wave feminists were warriors for dignity. The second wave fought to liberate the domestic. The third tried to reclaim sexuality from shame. The fourth lit the match of digital discourse. But none have fully developed an aesthetic of the intimate-but-undone, of the symbolic rehearsal, of consensual ambiguity as a site of feminine wisdom.

They have too often been Apollonian—cold, systemic, addicted to the language of rights and violations. Even when Dionysian currents were embraced—through rage, chaos, body-positive defiance—the structure was missing. And that’s the irony. Because the missing structure is Athena: the wisdom of knowing when to veil and when to unveil, when to strike and when to filter.

This is what Ukusoma offers: a syntax of desire rooted in agency, not commodification. A moment of sensual meaning that refuses to cash in. There are no billions to be made from it. No Super Bowl deals. No thirst-trap metrics. It’s not designed for the masses. It’s designed for the myth.

V.

H.E.R., in this reading, becomes a high priestess of sacred delay. Her artistry is now beyond protest. It is invitation, rehearsal, tease, offering—but all encrypted. And Billie Eilish, once the queen of the anti-gaze, is now experimenting with what happens when the gaze returns—but this time, on her terms. In both cases, the shift is not regression. It is recursion. A spiral, not a step back.

And let us say this clearly: this is only possible with full agency. A coerced ukusoma is no longer ukusoma. It is a betrayal. The entire power of this space lies in the fact that it is chosen. It is not adolescence. It is not delay out of immaturity. It is mature ritual withholding—Eden after consciousness, not before it.

VI.

The feminists will not understand this, not fully. Because it cannot be litigated. It cannot be tweeted. It cannot be packaged into a political campaign. It is too intimate. Too ambiguous. Too spiritual.

But the artists understand.

And maybe the lovers do, too.

VII.

So let the others chase virality. Let them monetize liberation. Let them misinterpret what power looks like. Meanwhile, Billie and H.E.R. will rehearse it—delicately, symbolically, one lyric at a time.

Because sometimes the most radical thing a woman can do…

…is almost undress.

…and then not.

That, my friend, is Ukusoma.

And it will not be televised.

Fig. 15 Poetry is a fractal unfolding of entropy and order.#

Josephine Baker: The Radical Choreography of a Life

I.

She danced, yes—but Josephine Baker’s real performance was a life. Onstage she was electric, magnetic, and wildly ungovernable. But offstage, she composed something more enduring than choreography: she curated a philosophical experiment in human dignity. Through movement, motherhood, and militant love, she refused the colonial categories into which she was born.

II.

Born in 1906 in St. Louis, Baker was never merely a Black entertainer abroad. She was an epistemic saboteur—a siren in sequins—seducing the very gaze that sought to own her. Her infamous 1926 “banana dance” was not naïve eroticism but weaponized parody. She became what the West fantasized about—and then shattered it from within. She didn’t just manipulate the white male imagination; she short-circuited it.

III.

The banana skirt was not consent. It was conquest. Baker’s brilliance was to twist the colonial gaze into a mirror—forcing Europe to confront its own grotesque longing. What she did in three minutes of dance, no manifesto could rival. The erotic was never just sensual; in Baker’s hands, it was dialectical—a form of embodied revolution.

IV.

But the stage was only Act I. Baker’s real genius unfolded in the quieter registers of exile and motherhood. Having secured a kind of freedom in France, she did not vanish into wealth or comfort. Instead, she undertook a utopian project as audacious as any armed revolt: she adopted twelve children from different racial and national backgrounds and raised them together in a castle she called “The Rainbow Tribe.”

V.

This was not liberal tokenism. It was metaphysical resistance. In an age where race, nation, and blood were fetishized by fascists and colonial bureaucrats alike, Baker said: No—humanity will be curated, not inherited. The Rainbow Tribe was a living repudiation of eugenics, segregation, and supremacy. She made her family not by chance, but by choice.

VI.

And she raised them not under one religion, but many. Muslim, Christian, Jewish, Buddhist—each child retained their inherited tradition. This was theological pluralism before it was fashionable. She was staging a drama not of assimilation, but of coexistence. The Rainbow Tribe was not a melting pot—it was a symphony.

VII.

In this, Baker anticipated and exceeded the rhetoric of multiculturalism. Her experiment was not symbolic—it was domestic. She didn’t just represent unity; she cooked for it, bathed it, educated it. Her castle in the Dordogne was a laboratory for post-racial futurism long before the term existed.

VIII.

This is why Angelina Jolie’s reference to Baker in 2003 is more than celebrity flattery. Jolie, too, sought to assemble a family that crossed borders and bloodlines. And she named Baker as her model. Not as a performer—but as a philosopher. Baker’s radical motherhood made her a prototype for a new kind of family, a new kind of love.

IX.

And yet—Baker never abandoned struggle. She was not a mystic in retreat. She returned to America during the Civil Rights era, stood beside Martin Luther King Jr., and refused to perform in segregated venues. She used her fame not to shield herself from pain, but to illuminate it.

X.

Even in death, Baker refused erasure. In 2021, she became the first Black woman interred in the Panthéon in Paris. Her body now lies among Voltaire, Rousseau, and Marie Curie. Not bad for a girl once barred from American hotels.

XI.

But this isn’t just a triumph narrative. To treat Baker as a saint is to miss her point. She was never pure. She was audacious, absurd, erotic, exiled, and extravagant. Her life was messy, theatrical, and endlessly performative. But that was the philosophy: not to escape contradiction, but to dance through it.

XII.

She is Beyoncé’s ancestor—not in blood, but in blueprint. When Beyoncé recreated the banana dance in 2006, it was not mimicry. It was homage. A nod to the original architect of aesthetic rebellion. Prada, Rihanna, even RuPaul owe her—not just for style, but for strategy.

XIII.

She made the body a weapon and the home a haven. She gave motherhood the aura of insurgency. She sang the “Le Jazz Hot,” but lived the Le Juste Vrai—the deep truth of a life that refuses to be explained in one language, one race, one rhythm.

XIV.

It’s tempting to historicize Baker—to fix her in the sepia tones of a Jazz Age Paris. But her ghost is everywhere: in the cries for justice, in the global adoptees who don’t fit a single label, in the fashion runways that dare to be tribal and futuristic at once.

XV.

And make no mistake: Baker was not just influential—she was dangerous. Because she offered not merely critique, but construction. She didn’t just expose the lies of whiteness and patriarchy. She proposed something else. Something impossible. Something radiant.

XVI.

This is what makes her so urgent today. In an age of retribalization and cultural retreat, Baker remains a beacon of hybrid possibility. She didn’t call for purity, but for plurality. Her family was a liturgy of hope, her dance a heresy against despair.

XVII.

Her legacy is not static. It’s viral. She is spliced into the DNA of resistance movements and avant-garde art. She echoes in ballroom drag, in Afrofuturism, in queer family structures. She is the mother of multiplicity.

XVIII.

Josephine Baker did not transcend race. She re-scripted it. She didn’t deny sexuality. She directed it. And she didn’t flee the stage. She turned the whole world into one. Her politics were not in pamphlets, but in parades, passports, and paternity papers.

XIX.

So let us not remember Baker merely for the banana skirt. Let us remember her for the children, the castle, the courage. Let us remember her for the choice she made: to live as if humanity were a thing still worth building.

XX.

She didn’t just dance in defiance. She mothered a movement. She choreographed a world.

🌊 Fitzgerald#

🚢 Baker#

🪛 🏴☠️ Turner, Madonna#

🦈 ✂️ 🛟 Spears, Beyoncé, Eilish#

🏝️ Ukusoma#

We are already electric. We’ve mapped a genealogy of womanhood, performance, and power not as a linear evolution, but as an epistemic ocean voyage—from abyssal voice to hyper-mediated spectacle. Let’s dive in, layer by layer, not neutrally, but sharply, lovingly, critically:

⸻

🌊 Ella Fitzgerald She is the sea. Unfiltered. Pre-ideological. Before the male gaze even knew how to commercialize it. Her voice wasn’t a performance of femininity—it was the sublime without costume. No choreography, no sex-politics tightrope. Just range. A Black woman commanding the frequencies of divinity through jazz, immune to ornament because she was the essence. Ella is the unedited waveform. The truth before its capture.

⸻

🚢 Josephine Baker The ship enters. Here we see myth and spectacle—Baker weaponized the colonial gaze by exaggerating it. She wore it like armor. Banana skirts and Parisian adoration—yes—but inside that, a sovereign will to survive and disorient. A woman who danced not just for applause but for escape, for statecraft, for espionage. She is performance-as-smokescreen, the masked queen on a ship built by men but navigated by her own subversions.

⸻

🪛🏴☠️ Tina Turner and Madonna Now we meet the pirates. The tinkerers. Tina: volcanic, ecstatic. She soldered trauma into electricity. Escaped Ike’s empire not by whispering but by shouting the house down. Her body wasn’t just sexual—it was discipline, machine, judgment day. Madonna: the white trickster. She didn’t escape violence; she anticipated it. She stylized the crucifix, kissed the devil, wore virginity as provocation. Pirate queen of reinvention. She grabbed the cultural wheel and steered it toward scandal. They both hacked the ship’s control panel—Tina with soul, Madonna with software.

⸻

🦈 ✂️ 🛟 Spears, Beyoncé, Eilish These are the crucible women. Born inside the algorithm, swallowed by the shark of spectacle, offered scissors to cut themselves out. Britney Spears: dissected by the media, sacrificed for entertainment, then buoyed by a digital uprising (“Free Britney”). Her life is the scissors. Beyoncé: crafted her raft with precision. She turned her marriage, Blackness, motherhood, even capitalism into an armory. A controlled storm. Billie Eilish: the anti-gaze gaze. She flooded the stage in oversized clothing to refuse commodification—then flipped it on her terms. Her whisper is more dangerous than a scream. She filters the shark.

⸻

🏝️ Ukusoma And finally: the island. Not salvation, but the representation of it. A place charged with contradiction. Ukusoma, in your framing, is both semantic climax and erotic ambiguity. Not quite consummation, not innocence either. A ritual, a riddle, a pause before reproduction. If Fitzgerald was the soul, Baker the spy, Turner and Madonna the mutineers, and Spears/Beyoncé/Eilish the ones wrestling the algorithm, then Ukusoma is the archive. The spellbook. The final pose that asks: “What now?” It’s not a utopia. It’s the memory of the voyage, told in gestures. The final performance not on stage, but in the code, in the source, in the text.

⸻

Absolutely. Here’s a 30-paragraph essay, structured around your five-stage epistemic journey—🌊🚢🪛🏴☠️🦈✂️🛟🏝️—and focused on the feminine voice and gaze through the lens of Fitzgerald, Baker, Turner, Madonna, Spears, Beyoncé, Eilish, and Ukusoma:

⸻

Ukusoma and the Feminine Voyage: A Mythology of Performance, Power, and Gaze

I. In the beginning, there was the voice. Not the stage, not the outfit, not the brand. Just the sound. Ella Fitzgerald didn’t seduce the ear—she possessed it. She didn’t perform identity; she transcended it. Hers was a Dionysian purity: improvisation as theology, each note a sermon of breath and precision. No feminism in name, perhaps—but absolute power in tone. She was the sea.

II. Fitzgerald’s place is not merely at the “origin” of a lineage. She is the abyssal origin, a force uninterested in self-narration. Her femininity was not curated, it was implied—eclipsed by a talent so vast it dissolved categorization. Her music is what the world sounds like before gender and race are parsed and monetized.

III. Then came the ship. The constructed world. Where culture codifies, where myth becomes export, where performance becomes diplomacy. Josephine Baker boarded it not as cargo, but as stowaway and queen. She danced on colonial scaffolding with the mockery of a goddess who knew the empire’s secret: it wanted to be fooled.

IV. Baker’s genius was double-coded. She leaned into the exoticism projected onto her, exaggerated it until it burst into satire. But satire was not her end—survival was. She was a spy, a war hero, an agent of state. Her banana skirt was a weapon, not an invitation. Her Paris was a stage, but her eyes looked past it.

V. If Fitzgerald’s sea was eternal, Baker’s ship was ephemeral—full of masks, masks on masks. Yet Baker smiled as she flipped the illusion. Her feminism was not declared but encrypted. She didn’t need a manifesto; she was the contradiction that no white ideology could safely absorb.

VI. Then came the pirates. The ones who had suffered, rebelled, rebuilt. Tina Turner was a volcanic engine of rage, soul, and ecstasy. She did not ask to be emancipated—she danced her way out of hell. And her boots had rhythm. Her body was not for you—it was hers, honed by war.

VII. Turner took what had been weaponized against her—her voice, her Blackness, her body—and used it to burn the stage down. She was not a survivor; she was a reconstructor. She didn’t just escape Ike. She reprogrammed what a woman on stage meant.

VIII. Parallel, with an entirely different code, came Madonna. A white woman with crucifix and lace, she performed blasphemy as theater and feminism as trickery. If Turner escaped a man, Madonna escaped a narrative. She flirted with dogma, but only to detonate it.

IX. Madonna’s feminism was never earnest. It was combative, provocative, calculated. She was the pirate queen who installed her own OS in pop culture’s motherboard. “Like a Virgin” was not vulnerability; it was a trap. The audience thought they were in control. They weren’t.

X. Tina and Madonna were engineers of persona. One emerged from ashes, the other from artifice. They both seized the ship’s controls—not to steer it to safety, but to prove they could. Their power was not in escape, but in hacking the system. Tinkerers. Rebels. Mythic thieves.

XI. And then came the algorithm. The shark-infested waters. The crucible stage. The surveillance mirror. Spears, Beyoncé, and Eilish didn’t just perform—they were monitored. Their feminism emerged in the teeth of attention, dissection, monetization.

XII. Britney Spears: girl next door, then caged icon. A teenager made into a product, sold as innocence, devoured as temptation. Her breakdown was not a fall—it was a revolt. And #FreeBritney was not just a hashtag. It was a scissors in the hands of millions.

XIII. Britney’s life became the battleground where media and agency collided. Her shaved head was anti-narrative. An escape from the algorithm. A refusal of the gaze. Her silence was the scream.

XIV. Then Beyoncé. The meticulous builder. The cultural choreographer. Her feminism was deliberate, unflinching, designed like a cathedral. She wrote Blackness into the software. She turned pain into spectacle, love into labor, motherhood into gold.

XV. Beyoncé is the raft. She floats above the sharks by mastering the rhythm of the waves. Her albums are not songs; they are blueprints. Her performance is not rebellion—it’s dominion.

XVI. Enter Billie Eilish. Whispers instead of belts. Baggy clothes as armor. A teenager who refused the archetype. She didn’t say “I am not for sale”—she implied it. And implication was enough. Her gaze is spectral. Her fame, haunted.

XVII. Billie’s feminism is post-verbal. Her affect is deadpan, her lyrics dissonant, her fame algorithmically suspect. She turned off the spotlight and became more visible. She is both shark and buoy—terrifying in her refusal to flinch.

XVIII. Together, these three didn’t escape the crucible. They recast it. Spears cracked it. Beyoncé consecrated it. Billie re-coded it. Their scissors weren’t just tools of escape; they were instruments of revision.

XIX. And so we arrive at the island. Not paradise, not reward—but representation. Ukusoma. A term shimmering with ambiguity. Not just the act, but the meaning of contact. The pause before ideology takes over. The edge between knowing and naming.

XX. Ukusoma is not a person but a state. A glyph. A riddle. It is the whisper of the feminine in a world that now monetizes even whispers. It is not pre-capitalist—it is post-performance. It is where narrative collapses back into myth.

XXI. If Ella is the sea, Ukusoma is the memory of the voyage carved into the sand. If Baker wore the mask, Ukusoma is the mask-maker. If Madonna shocked and Beyoncé crowned, Ukusoma is what happens after the applause.

XXII. It is a silence that isn’t passive. A ritual that doesn’t end in climax. It is the aesthetic of potential—dangerous, sacred, incomplete. Feminism here becomes not assertion, but cipher.

XXIII. Ukusoma resists capture. It is not a TED talk. It is not a thesis. It is not a revolution. It is the cool hand pulling the curtain closed. Not to hide, but to signify: the real performance is what you didn’t see.

XXIV. In an era of cameras and clicks, Ukusoma withdraws. It is not refusal, but recursion. Not exile, but encryption. It remembers the sea, the ship, the pirates, the crucible—and says: none of these were the end.

XXV. It is the Island as metaphor, not geography. The end of spectacle, the beginning of symbol. It’s the moment a woman closes her eyes on stage—not in exhaustion, but in command.

XXVI. Feminism, here, is not just about rights or equality. It is about enchantment. The ability to distort, to withhold, to transfigure. To survive the sea, hack the ship, slip past the shark—and still dance.

XXVII. Every woman in this essay is a stage in that mythic journey. They are not in competition, nor on a ladder. They form a fractal. A feedback loop of voice, costume, scream, whisper, and silence.

XXVIII. To study them is not to study fame—it is to study sorcery. These women are not celebrities. They are systems of meaning, each refining what it means to be seen, to be heard, to exist in performance.

XXIX. Ukusoma is the last gesture. The final glance. The island at dusk. Not an end, but a punctuation. A new beginning wrapped in ritual, ambiguity, and fierce remembrance.

XXX. And in that final pose—one hand raised, one foot barely touching the stage—we see it: not escape, not triumph, but transmission. The legacy of gaze turned inward. The echo of Ella in the future’s mouth. The island is not a place. It is a gesture. Ukusoma.

⸻